I often carry a notebook when I go hiking in case I see something I want to remember. This spring, the first time I ever hiked the Fall Creek Unit in Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, ancestral Awaswas land, I wrote, “Is there a word for the way sunlight filters through leaves in a forest?” The way the light illuminates the leaves, setting their undersides aglow. The rays streaming around branches in penetrating beams in what I’ve heard several people call “Jesus lighting.” Or diffusing softly, dappling the canopy to the forest floor ferns in a tapestry of green. The answer is yes—there is a word for it. It comes from Japan, where the healing concept of forest bathing also originated, and the word is “komorebi.”

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Explore: Redwood Forest

»The Lime Kiln Trail to Kiln Fire Road is an out-and-back trail, just over 3 miles roundtrip, with mostly level terrain. It’s a pleasant, invigorating walk that follows the burbling Fall Creek for much of the way.

»Small, no-fee parking lot at 1101 Felton Empire Road in Felton. No designated ADA parking.

»No bathroom facilities or running water.

»Maps at major junctions of the trail, including the beginning.

»No dogs or bikes allowed, but horses are OK.

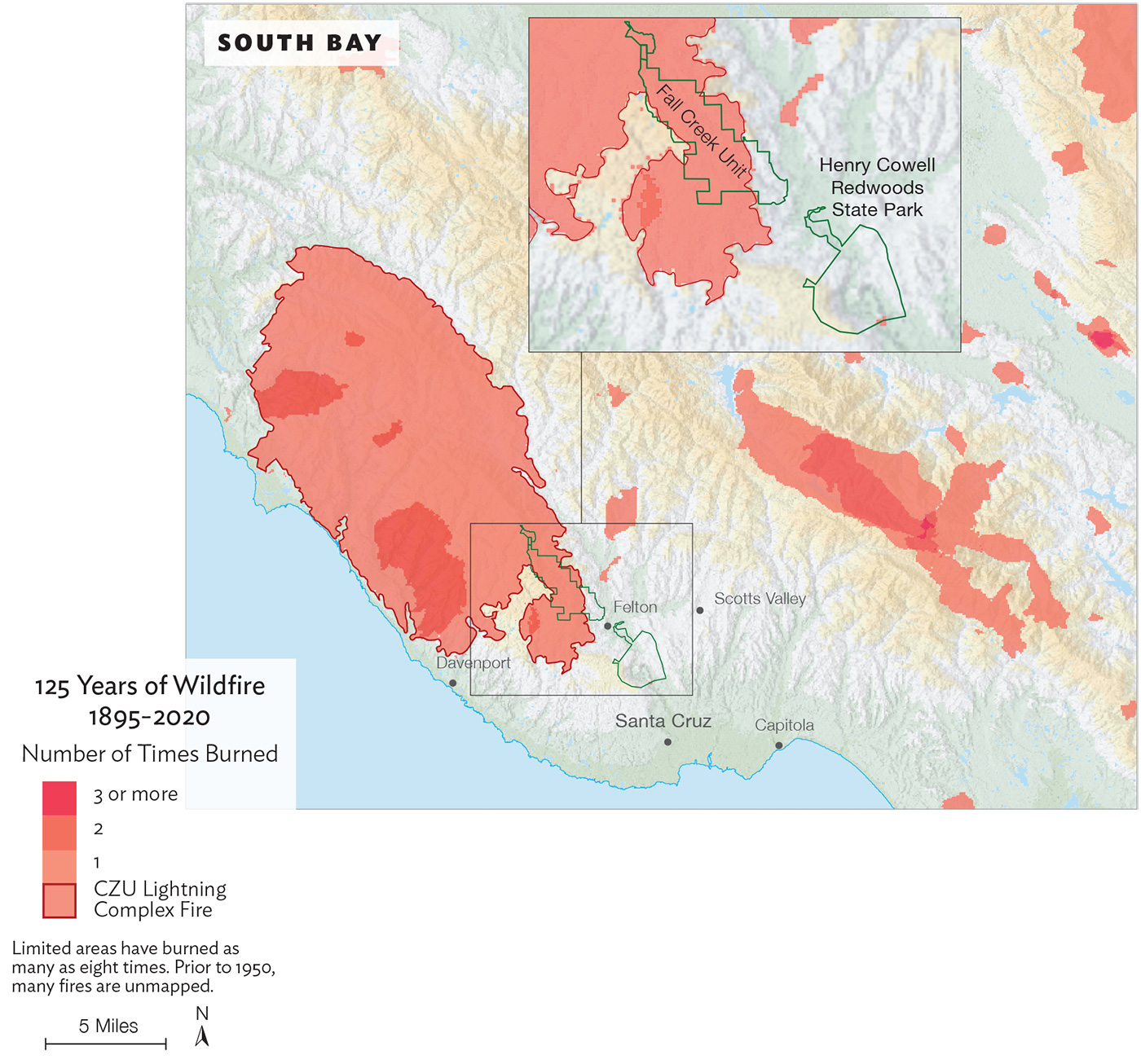

I think about this—what quality the komorebi will take today—as I roll up in my car, gravel crunching and dust kicking up, to the Fall Creek Unit parking lot, just north of the UC Santa Cruz campus. I’m here to hike the Lime Kiln Trail to Kiln Fire Road, which follows Fall Creek through a canyon of redwood forest that changes from lush, shaded hillsides with century-old second-growth trees to an area that burned, for the first time in a hundred years, in the CZU Lightning Complex fires in August 2020. This bit of Henry Cowell is among the 86,509 acres that went ablaze in the Santa Cruz Mountains fire, much of it in redwood habitat. Car parked, water bottle in hand, I set out to travel through time as I move from a sample of the past in an unburned forest to the present almost a year after the burn.

Fall Creek runs through a granite and limestone canyon that from the 1870s to 1919 was a lime quarry; the area was logged extensively to feed the kilns for making limestone, and you can see the remnants of the kilns today. After quarry operators logged an area, they probably burned the ground to clear the debris. Unlike the fire traditionally used by Indigenous people to steward the area, the lime production process and fires stripped the land of resources. When the trees grew back, they did so all at once, resulting in a forest of densely packed, skinny trees.

The lime quarry shut down in 1919, and the logging and fires stopped. In 1972 the land was gifted to the California State Park system, and the forest has been recovering since without intervention, its logging past visible in the crowded patches of slim trees. A redwood that is young and skinny has less thick, fire-resistant outer bark than older ones. And growing closely together, the trees make it easy for fire to jump and spread through their crowns. A second-growth forest like this reflects its history and is more susceptible to intense fire.

Nonetheless, the understory appears to be thriving. A measure of a forest’s health is the diversity of its native plant communities. Hiking this trail, I see bouncy redwood sorrel, like forest shag carpets, covering the ground. There’s also miner’s lettuce, with leaves like shiny green saucers on sticks and tiny white flowers at the center. High in vitamin C, it was popular among miners to stave off scurvy—a remedy they learned from Indigenous tribes who’d been enjoying the plant long before prospectors arrived.

A whiff of spice, both herbal and floral, says you’re near a California bay laurel. Indians had many medicinal uses for the bay tree, including curing headaches by either wrapping the leaves around the head or stuffing leaves up the nose. The bay’s slender trunks splay out from the base, reminding me of octopus arms. Looking up, you might notice leaves appearing to glow as the light shines through them; they likely belong to big-leaf maples. The California hazel has roundish fuzzy leaves with delicately serrated edges that you can identify because they’re “soft like toilet paper,” a botanist friend told me.

I reach the junction with Kiln Fire Road, and I begin to notice signs of the fire. The lightning storm that struck the Santa Cruz Mountains in August 2020 lit a blaze that eventually became the CZU Lightning Complex fires. A significant portion of the Fall Creek Unit burned, leaving many trails closed due to fire-caused hazards, like hard-to-see pits in the ground created when flames blazed down through tree roots into the soil. Kiln Fire Road, though, has reopened and is safe to access. It passes through the post-fire forest that I have come to see.

“From the natural resource perspective, I wouldn’t even call this a disaster,” says Joanne Kerbavaz, senior environmental scientist with California State Parks (CSP). I meet up with Kerbavaz to walk the burned section of the trail and find out how the forest is recovering. “I think the impacts are hard for us to [witness] as humans, but I really am feeling that in the life of a redwood forest, this area’s seen worse,” Kerbavaz says.

It’s clear that a fire has burned through this area of mixed evergreens. On one side of the trail the century-old forest, untouched by the flames. On the other, blackened redwood trunks and scorched tanoaks rise from dry silty soil. The sunlight here gleams off of sparkly charcoal trunks. The trail is dusty and a faint smell of soot lingers in the air. I hear more bugs clicking than I do birds chirping. Kerbavaz, though, is drawn to everything that’s still green. Commenting on the redwood sorrel that has “happily sprouted from roots that were still alive in the soil,” she declares. “Partially I’m an optimist and partially it’s just my interest in how nature is responding to this event.”

As we walk along the trail, an occasional yellow comma flecks the ground at the base of a tree or among the sorrell—banana slugs! “It’s surprising,” Kerbavaz says, “that in this area of very low-to-moderate-intensity [fire] and even in some of those intensely burned areas, we’re finding salamanders, things you wouldn’t think would be able to ride out a fire.”

How do these moisture-loving critters do it? “I think they just find moist places underneath the duff,” she says, pointing to the damp soil at the base of a redwood. Duff—leaf litter, fallen branches, and sloughed bark—decomposes and becomes soil. Voluminous redwood duff, which is slightly acidic from tannins in the bark and leaves, “helps suppress other plants growing up, and it provides habitat for the things that would burrow underneath,” Kerbavaz explains. Deeper duff often contributes to more intense fires that burn hotter and longer, and here in the Santa Cruz Mountains, it can go down four feet in some places that haven’t seen fire in over a century.

I notice that the soil seems finer and dustier here than back by the creek, but it doesn’t seem like the soil has burned intensely. “Hypothetically, fire temperatures can cause chemical changes in the soil,” Kerbavaz says. Judging by the understory’s immediate regrowth along this trail, it’s unlikely that happened here. “There doesn’t seem to be any obvious visual difference in the soils in those areas,” she says, pointing at charred trees nearby. A little creek runs underneath one of the redwoods, and if you poke the soil near the base, it’s moist. There’s even moss nearby that’s still—or already grown back—lime green. Soil that burned in higher-intensity-fire areas, though, may be a different story, and scientists are currently collecting and analyzing samples.

We come to an area dominated by tanoaks. From trunk to crown, they are brown. To me, the tanoaks look crispy and dry, but Kerbavaz explains that the fire was actually “pretty gentle in here,” judging by the height of the flame licks marking the trees. The technical term is “flame length,” a measurement that helps researchers determine the intensity of the fire. Gazing at the black ghostly outlines of where the fire touched wood, I can picture how tall the fire was as it moved through the forest.

For most of the hardwoods—tanoak, live oak, California bay, madrone—when a fire rolls through, the aboveground part of the tree will die. “That’s one of the things I never quite realized about the tanoak,” says Kerbavaz as we walk past a stand of them mixed with madrones. “They look fine. They hold on to their leaves. They don’t look like they’ve burned,” she says, tilting her head to peer up at the crowns, “but the leaves scorch and the tree dies.” After millennia of living in California’s fire-prone landscape, though, many of these species are fire adapted. Big-leaf maple resprouts from the unscorched roots underground. So does California hazelnut, traditionally used by Indigenous tribes for weaving. After a fire, hazelnut sends up straight unbranched shoots, perfect for weaving intricate baskets. Tribes planned some cultural burns specifically to harvest these hazelnut shoots. A cluster of green shoots at the base of a tanoak catches Kerbavaz’s eye—“Well, I can see here there are some that are already resprouting!”

“The only tree here that doesn’t respond well to fire is the Doug fir,” Kerbavaz adds. Douglas firs are not as fire resistant as redwoods nor resilient resprouters like the hardwoods. A fire can burn down through the roots, killing the tree and creating those dangerous fire pits—one of which Kerbavaz accidentally stepped in during the past week. Still, when the duff layer is burned through, it returns nutrients to and exposes the soil. This allows new seeds, like the Doug fir’s, to germinate, she explains.

As an integral part of California’s landscape, periodic fires ignited by lightning strikes or Indigenous tribes have helped keep a redwood forest healthy and prevent flammable plant matter from building up, reducing the likelihood of the type of extreme fire we saw last year. But there’s no formula for how often a redwood forest should burn. It’s subjective and based on the forest’s condition, like the amount of duff or stress from drought. “Some people say [in the past] we had fires every five to 10 years, and some people say the interval was 20 years. Nobody really knows,” Sarah Collamer, Cal Fire forester for Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties, told me. Holding a prescribed burn today, though, is tricky. In addition to the trifecta of wind, temperature, and humidity that makes for good, low-intensity fire conditions, getting a permit here in the coastal region is “an incredibly complicated process, incredibly expensive, and so it’s very prohibitive,” Collamer said. It’s hard to say when the next burn will be in these parts.

Also in the area, the Amah Mutsun Land Trust (AMLT) is working to revive cultural burning in Mutsun and Awaswas territories, which historically stretch from south of San Francisco to north of Monterey Bay. “Fire,” says Lawrence Atencio, natural resources manager of AMLT, “is a gift from our Creator and connection through to the spirit world—and also can be utilized as a management tool to restore.”

Atencio leads AMLT’s Native Stewardship Corps, which connects tribal members to the Indigenous stewardship work of their ancestors, like cultural burning. Atencio is hopeful that his work with the Native Stewards to carry out regular, low-intensity burns will restore ecological balance, wildfire resilience, and “that sacredness to Mother Earth,” he says.

“One of the silver linings of this fire is that all of the landowners, all of the people working in these ecosystems, are probably going to collaborate,” Kerbavaz adds, rather than focusing on their individual property and disregarding issues impacting the larger landscape.

As we get to the end of the Kiln Fire Road, we see a black phoebe flit across the path. The sunlight is bright through gaps in the canopy as Kerbavaz adds, “I hope this is the kind of place people would come to and see how quickly it’s going to recover.” As I start to double back for my return trip, I’m excited to look for all the signs of life along the path. The sun, now overhead, is dazzling as it dances on charcoaled chunks of yesterday’s trees—which will help tomorrow’s forest flourish. It’s the same trail, but a different point of view.