On a warm Friday afternoon, a group of kite surfers sat on the crushed oyster shell beach at the end of San Mateo’s Third Avenue and waited. The surfers were ready to go: wetsuits on, neon-colored kites inflated and resting on the beach like tents at a mountain camp. They needed only that familiar Bay Area afternoon breeze to kick in, and everything would be perfect. Except that Mother Nature, this day, was letting them down.

“The forecast is bad,” said Serge Nadon glumly, sitting and staring out at the Bay. “We need the pressure differential.”

No one’s got their finger on the pulse of the Bay Area’s wind quite like the surfers and sailors who depend on it for their favorite pastimes. Fortunately, wind is a pretty reliable feature of the Bay Area summer. The reason, as Nadon says, is the pressure gradient.

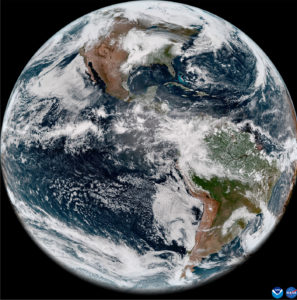

In summer, the sun bakes inland areas, heating them up, causing the air to expand, and lowering the pressure. The coast stays relatively cool because of the cold ocean water, meaning the air is denser and higher pressure. Air flows from high to low pressure, so the greater the difference in temperature between interior and coast, the stronger the westerly winds.

“You have this relatively cool air over the Pacific that has relatively higher pressure than the low pressure inland,” says Jan Null, a private weather forecaster who runs Golden Gate Weather Services. “That’s the sea breeze in a nutshell.”

That explains why the wind is strongest in the afternoon–Stockton and Concord heat up all day while San Francisco stays essentially the same temperature, creating the greatest pressure differential. It also explains why the sea breeze slackens in September: As the days get shorter, there’s less sunshine to heat up the interior.

In the Bay Area, the sea breeze is amplified by the landscape. The wind is blocked by the hills along the coast, like water behind a dam, so where it has an opportunity–the Golden Gate, Altamont Pass–it rushes through. That accounts for the orientation of the runways at San Francisco International (to allow planes to take off into the prevailing wind funneled through the San Bruno Gap); the windmills along Highway 580 in Livermore; and, of course, the windsurfers, kite surfers, and sailors at Crissy Field, Third Avenue, the Berkeley Marina, and Sherman Island (near Antioch).

As important as the sea breeze is here, its future is uncertain. Many of the big-picture conditions that affect the wind–air and sea surface temperatures in particular–are changing with global warming.

One paper from Santa Clara University researcher Bereket Lebassi suggests that relatively higher interior temperatures over the last 35 years have increased the pressure differential and, therefore, the wind. As the interior continues heating up, the coast could see more fog and more wind in the future, Lebassi concludes.

But in 2010, two UC Berkeley scientists published a study suggesting that the coastal cooling and interior heating over the last 35 years is a minor anomaly in a century-long trend toward a decreased temperature differential. That paper suggests the smoothed-out gradient has led to a 33 percent decrease in the frequency of fog in Northern California since the early 1900s. (Fog and the sea breeze are related, products of the same big-picture conditions–something like “first cousins,” says National Weather Service Science Officer Warren Blier.)

As scientists continue to untangle the future of the Bay Area’s weather, though, wind surfers, kite surfers, and sailors are happy to take advantage of present conditions–when they can.

Come summer, said Nadon and his buddies, they’ll be out on the water four, five, even six times a week, when that steady northwest wind, funneling through the San Bruno Gap and past the airport, rises just about every afternoon to a perfect 20 to 25 miles an hour.

“We’ll get a good pressure gradient and it’ll kick in for everyone,” Nadon said. “If we’re driving up and see the fog, we get excited. We know the pattern.”