It was a gorgeous blue-sky, green-hills spring morning when we arrived at our destination in Corral Hollow in eastern Alameda County. We climbed over the closed fence and made our way into a beautiful and serene Inner Coast Range valley lined with cottonwoods and sycamores and surrounded by hills dotted with blue oaks, buckeyes, gray pines, and an abundant array of spring wildflowers.

A few weeks earlier, soon after the publication of the first issue of Bay Nature magazine in 2001, I had received a call from Steve Edwards, then-director of the Regional Parks Botanic Garden, concerning an imminent threat to a biologically significant but little-known open space east of Livermore. It was the first I had heard of Tesla. (Back then, the name “Tesla” conjured up the eccentric late 19th-century inventor Nikola Tesla, not the comparably eccentric Elon Musk and his electric car company.)

Edwards explained that the Off-Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation (OHMVR) division of California State Parks had purchased the property and was planning to incorporate it into the nearby Carnegie State Vehicular Recreation Area (CSVRA). This was alarming because of the rich and diverse biological and cultural resources Edwards said were on the property and the likelihood that those would be lost forever if motorized all-terrain vehicles were allowed free rein. He proposed that Bay Nature run an article to highlight the issue and offered to write it himself. I agreed and we set up a time to visit the property with a photographer to document the scenic and biological value of this place. The article, “The Vale of Tesla: Natural Beauty/Human Designs,” appeared in the October–December 2001 issue of the magazine.

Now, almost exactly 20 years later, it appears that the area known informally as “Tesla Park” has finally been saved, with the signing on September 23 of SB155, the Public Resources Trailer Bill of the 2021–2022 state budget. In section 21 of this bill, the state of California declares that the 3,100 acres of the “Alameda-Tesla Expansion Area … shall not be designated as a state vehicular recreation area.” In return, the state will transfer $29.8 million to the Off-Highway Vehicle Trust Fund, which can be used to develop “properties to expand off-highway vehicle recreation.”

State Senator Steven Glazer (D-Orinda) and Assemblywoman Rebecca Bauer-Kahan (D-San Ramon) were deeply involved in the negotiations over the bill. “This is a win-win for all involved,” a press release from Glazer states. “Our community and region gets to preserve this natural and cultural treasure while the off-road enthusiasts will keep their current park and receive funding to develop another park on land that is more suitable to that kind of recreation.”

This outcome is the result of a battle spanning the past two decades, with organizations such as the Sierra Club, the California Native Plant Society (CNPS), Greenbelt Alliance, Save Mount Diablo, and others banding together with the Friends of Tesla Park (formed by several nearby ranchers and residents in 2011) to oppose expansion of the vehicle recreation area. The environmental groups organized letter-writing drives, filed lawsuits, and brought bills to the state legislature. Several earlier bills intended to protect Tesla had either failed to pass or been vetoed by the governor at the time. But then a state court decision earlier this year ruled that the state’s environmental impact report for expanding CSVRA was invalid and directed the OHMVR division to start the process over. That appeared to open the way for the negotiations that led to the current agreement.

So, then, what has all this fuss been about? Why is Tesla special enough to warrant such a long and bitter battle?

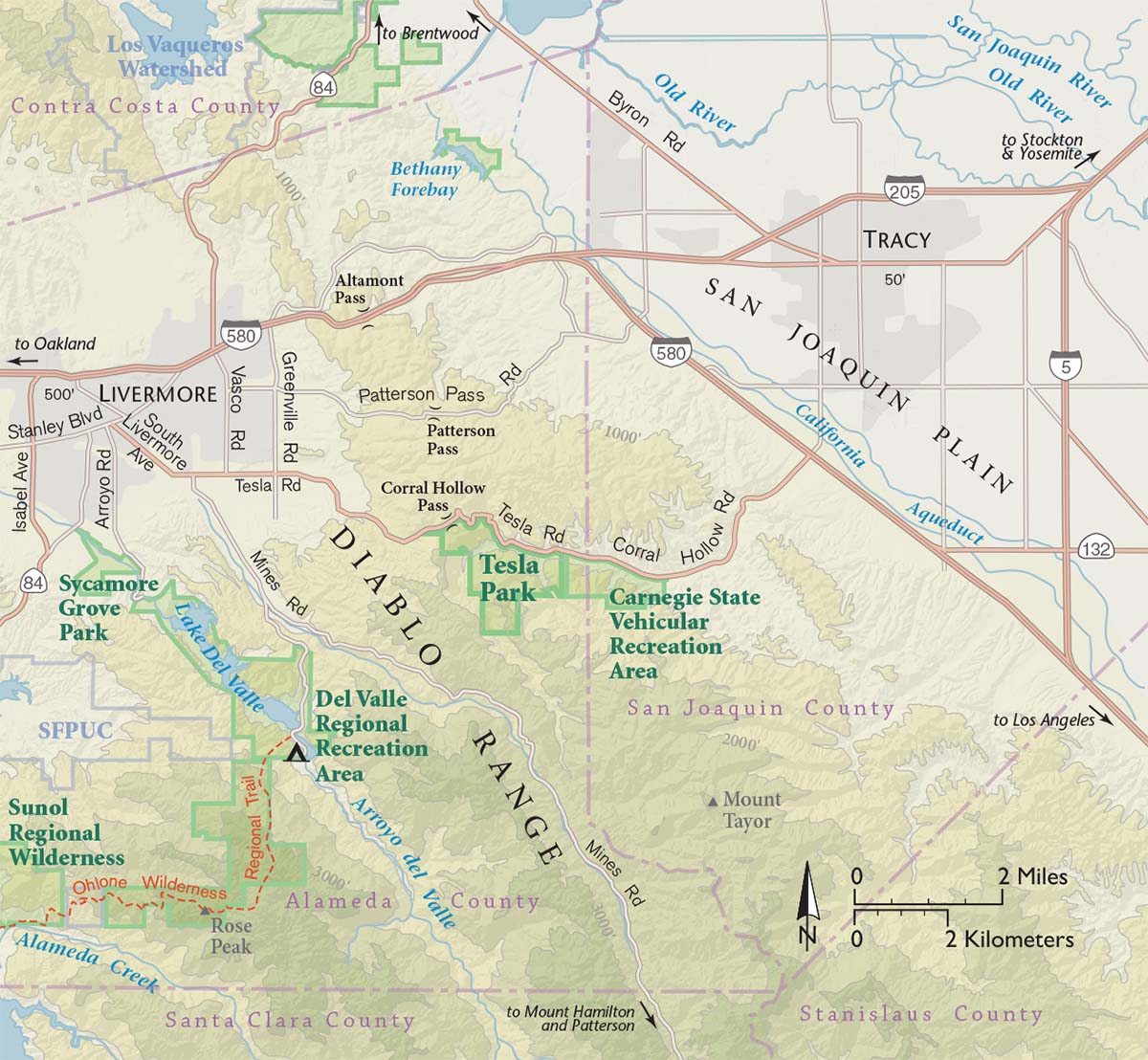

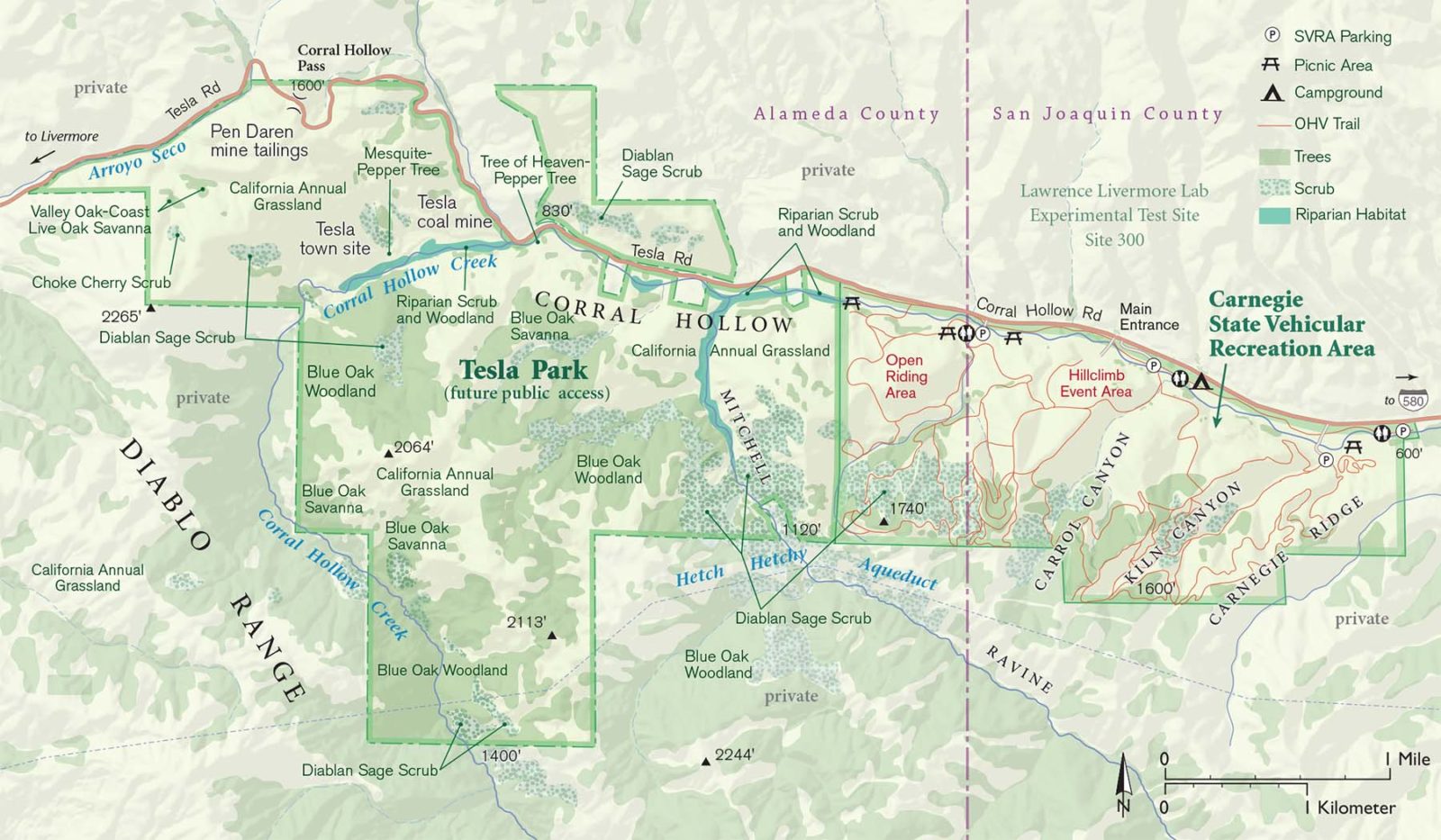

According to Heath Bartosh, senior botanist at Nomad Ecology and member of the CNPS Rare Plant Program Committee, Corral Hollow is significant ecologically because it sits at the junction of the Coast Ranges and the San Joaquin Plain and is the northernmost of a series of east-west-trending valleys running from the Diablo Range into the valley. As such, it is the northern limit for a number of desert-adapted plant, bird, reptile, and amphibian species. Bartosh, who conducted botanical surveys of Tesla in 2015–16, says Corral Hollow is a convergence zone where species that we might expect to find in the Mojave Desert coexist with species more familiar to those of us from the Bay Area. He describes how they probably moved up into the area during a period 8,000 to 5,000 years ago, at the end of the Little Ice Age, and have remained because of the remote nature of the valley. “It’s one of the healthiest and more intact ecosystems in the East Bay,” he says.

Given this combination of rare habitat and proximity to the Bay Area, the Tesla site has been a magnet for studies by Bay Area scientists and their students for many decades. Bruce Baldwin, a professor of Integrative Biology at UC Berkeley and director of the Jepson Herbarium, has observed that “the Tesla property harbors an unusual array of vegetation types, including rare assemblages such as desert olive scrubland, and the habitat quality is particularly notable.” Others who have conducted studies at Tesla include renowned UC Berkeley herpetologist Robert Stebbins, who wrote in 1980 that “because of its accessibility and unusual flora and fauna, Corral Hollow is an outstanding wildlife resource area for the people of the Bay Area.”

In 2010, the East Bay chapter of CNPS designated the property a “Botanical Priority Protection Area,” one of 15 in the East Bay. Plant surveys conducted in Corral Hollow found 76 species that are considered locally rare and significant, 35 of which are at the northern limit of their ranges here. Bartosh points out that this is particularly significant in a time of climate change, when organisms at the limit of their range are more likely to be adapted to changing conditions. Moreover, Corral Hollow is also considered an important wildlife habitat corridor, with intact habitat leading from the rugged Diablo Range down into the San Joaquin plain: In 2013, it was classified as a “Critical Linkage Wildlife Habitat Corridor” by the Upland Habitat Goals Project of the Bay Area Open Space Council.

Tesla is notable for its cultural resources as well. It is a village site of significance within the ancestral homelands of the Yokuts and Ohlone peoples and appears to hold several sacred ceremonial sites. It later became the site of the town of Tesla, serving one of the Bay Area’s most important coal-producing areas, where mining helped fuel much of the growth of the Bay Area from the late 1850s until 1915. Some 1,500 people lived here at the mining industry’s height.

Evidence of the former inhabitants of Tesla can be found along and above the valley floor, from the abundant rock mortars in sandstone outcroppings by the creek to the mine tailings farther up the valley, as well as in several level areas on slopes above the creek where buildings once stood. Now, though, nature has mostly reclaimed the place, allowing its surprising diversity of plants and animals to thrive.

That’s why advocates for Tesla Park, such as Beth Wurzburg, who represents the Conservation Committee of East Bay CNPS, are thrilled by the latest developments. “This is fantastic news; we’re delighted that Tesla has been saved,” she says. “Places like this are rare and the opportunities to save them even more so. But Tesla should never have been considered for off-road vehicle recreation in the first place.”

Celeste Garamendi, a rancher in Corral Hollow and one of the founders of Friends of Tesla Park, concurs. “This is a great accomplishment,” she says, “the wonderful result of a collective effort on the part of so many people and organizations over 20 years.” But “now we have to ensure that it receives the highest level of protection in the planning process.”

Both Garamendi and Wurzburg also tempered their elation with further notes of caution. Their first concern relates to the amount of money paid to the OHMVR division for the Tesla property itself. While no one objects to repaying the original purchase price ($9 million), the agreement calls for the payment of some $18.3 million for the property, which OHMVR contends includes appreciation plus money it spent on maintenance and planning. Wurzburg and Garamendi consider this figure highly inflated. Even more controversial is the $11 million included in the agreement for the purchase of land for another OHV park elsewhere. OHMVR is supported by a dedicated stream of vehicle registration fees and gasoline taxes, which makes it the most reliably funded part of the State Parks department already, while non-OHV parks remain chronically underfunded. However, Wurzburg adds that even while the total price tag of $29.8 million is higher than it should be, “saving Tesla is worth it.”

The most troubling aspect of the agreement for park advocates is a clause acknowledging the OHV lobby’s long-expressed desire to open up sections of existing state parks to off-road vehicle use. One park specifically mentioned in this part of the legislation is Henry Coe State Park in the Diablo Range in southern Santa Clara County, the largest state park in Northern California. OHV proponents have specifically targeted Coe for many years because of its extensive rugged and wild backcountry areas, which they claim are “underutilized.”

The addition of this clause took park advocates by surprise, as it was not part of the public negotiations. They don’t know who inserted it and when. Garamendi says she assumes it was a concession to the OHV lobby. But, she points out, there is no express approval in the bill for any such expansion, which also couldn’t happen without an extensive EIR process and public hearings. “Nonetheless,” she cautions, “it will be incumbent on the conservation community to stay engaged to ensure that this doesn’t happen at Coe or any other state park.”

Park advocates also will need to remain engaged as the state moves into the planning stage for Tesla. Advocates such as Friends of Tesla Park, Sierra Club, and CNPS are going to push the state to classify Tesla as a “natural reserve” and a “cultural reserve” as defined in the California Public Resources Code 5019.65. Such designations would mandate protection of the natural and cultural resources as the priorities for management. Passive recreation would be allowed and encouraged, but it would remain a secondary priority. A statement from the State Parks public relations office reads, “California State Parks looks forward to the future planning of the Tesla-Expansion Area, including the classification and naming of the unit by the California State Park and Recreation Commission. Once the park unit has been classified, planning efforts can be initiated that identify new public recreational opportunities.”

SB155 authorizes $1 million to support a public planning process. “We want it done right,” Garamendi says. “It can be a new model for state park planning, putting resource protection at the center and informed by the crisis of the day: climate change. And it should be a broader process, involving local Native American groups, conservation groups, municipal and county agencies, local ranchers, botanists and other scientists, and historic preservation experts.”

All of this will take time—though, one hopes, not too much time. In the meantime, the golden eagles, roadrunners, kit foxes, tiger salamanders, San Joaquin coachwhips, and spadefoot toads can continue to flourish on this tranquil and diverse landscape, likely oblivious to all the energy, time, and money invested in keeping it protected for them … and for us.