Lobos Creek trailhead in the Presidio looks wild. Flushed orange monkey flower, sage, and coyote bush spill over re-created sand dunes. Nearby, the creek empties into the ocean. But close your eyes. A water truck pulls up to a stop sign with a mechanical whine. Car engines growl, foghorns moan, a distant airplane whirs. The noise, which never stops even though it’s barely 7 a.m., makes it clear you’re in the middle of the city.

In the parking lot, a white-crowned sparrow perches at the top of an evergreen tree next to a pickup truck and sings, launching a quick patter: whistle, buzz, two-part trill, and a scattering of notes. It’s music familiar to city dwellers, even if they couldn’t name it. The song is key to the white crown’s survival, helping him attract a mate and defend the territory around his nest, warning off other males with his vocal vigor. But the notes are almost drowned out as a bus sighs to a halt. Thanks to recent restoration efforts, the bird is surrounded by plants, such as lupine, that evolved here over centuries, along with the sparrow. But there is no restoring the silence, and the noise grows year by year. What will it take for white crowns like this one to survive in this new soundscape? What will it take to be heard?

Down the boardwalk, David Luther, a quiet-voiced, rusty-haired biologist from George Mason University in Virginia, is trying to find out.

“In the past ten years or so, there has been mounting evidence of how human noise is affecting these birds,” says Luther. Not just birds, he adds, but other animals, too. Studies in the developing field of “acoustic ecology” show whales, crickets, and frogs altering their behavior in response to man-made sounds. While some flee the cacophony, others adjust their internal clocks. Along a river near the Madrid airport, nightingales and European goldfinches sing earlier in the morning before the roar of the planes starts up. In Sheffield, England, robin redbreasts in noise-cluttered areas have started to sing at night. The whole “dawn chorus” has moved away from dawn. And others, like the white-crowned sparrows, are changing their tunes.

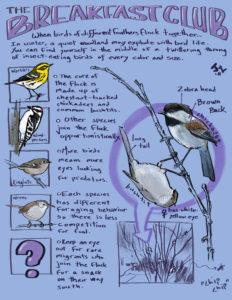

Bay Area white-crowned sparrows are famous in ornithological circles for their flexible songs. Like many songbirds, white crowns develop dialects specific to certain areas, the way a California drawl in Humboldt County differs from one in Los Angeles. But their dialects are so distinct, the boundaries so sharp, they have become a subject of choice for researchers studying song learning and evolution. As early as the 1960s, researchers found that San Francisco resident white crowns sound markedly different from those in Marin, just a few miles away. In the East Bay, white crowns in Tilden Park sang different songs than those in Richmond or ones that lived by the Bancroft Library, replacing a trill with a buzz, or swapping out a jumble of whistles. Scientists charted ten dialects in parts of the Bay Area and tracked patterns shifting as a bird became bilingual or a migrant singing a new variation passed through.

But now a new pattern is being carved out. As Luther props up a wooden sparrow on a stick near a saddle between sand dunes, at a spot where a male guards a nest, he is taking 50 years of white-crowned sparrow studies in a fresh direction, gauging the impact of the increasingly noisy city on bird songs.

There’s no doubt they are changing. Luther and his colleagues have documented that these Presidio birds have clearly shifted to a dialect more audible above the urban din. And they sing even that dialect at a higher minimum frequency than in past decades, likely in an effort to rise above the low-frequency rumble of cars. Now the researchers want to understand how the birds made that change, and more important, at what cost, catching a glimpse of the future of the song, and the bird, and the nature of the city.

“What are the potentially evolutionary effects?” he asks, setting up a speaker in the male’s territory. He’s preparing to play a rival’s song, either a traditional one or one at an even higher minimum frequency, and take notes on the white crown’s response. “Do the birds care, and how do they care?”

Luther sits in the dirt, presses Play, and waits.

All over the world, as the urban footprint expands, scientists are asking how cities are reshaping nature. Peregrine falcons nest in skyscrapers. Coyotes dodge cars in downtown Chicago. Studies have shown that city shrews in Minnesota have larger brains than their rural counterparts, that city song sparrows are more aggressive, that white-footed mice in New York contain genetic mutations not present outside the city.

Increased noise is one of the most prominent and damaging effects of urbanization: Car alarms screech and buildings create urban canyons filled with echoes. In Nova Scotia, American tree swallow young exposed to high levels of noise begged less at the sound of a parent arriving at the nest. Perhaps because they couldn’t hear it. The youngest birds rely most heavily on sound, as their eyes don’t open for several days. And humans are not immune. People living with constant noise have increased levels of stress hormones and risk of heart attacks.

Many birds vanish from areas as noise increases, including the Pacific wren and Swainson’s thrush. Those that sing at lower frequencies, or rely on sound to catch their prey, or nest in cavities seem particularly hard hit. Others, like house sparrows and crows, thrive in city life. The white-crowned sparrow and species like it seem to be occupying territory in between—not exactly thriving in the city, but not disappearing either. They are adapting, possibly evolving. Feeling around for a way to somehow hold on.

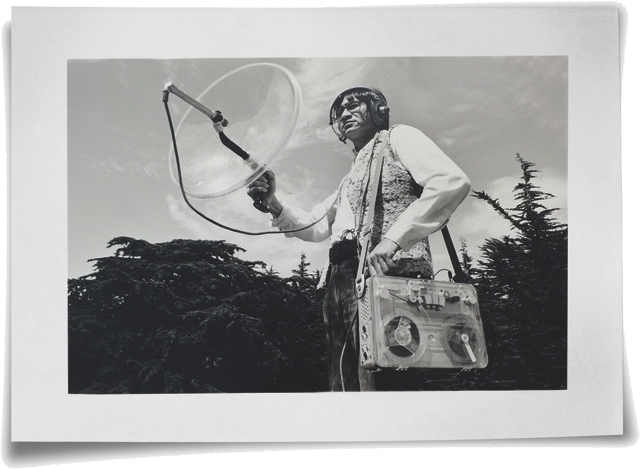

The man who brought Bay Area white-crowned sparrow communication to the world’s attention was an ornithologist originally from Hong Kong and Macau named Luis Baptista. In the late 1960s and ‘70s, Baptista began recording white-crowned sparrows near where he lived and worked: the California Academy of Sciences, Lake Merced, Union Square, the Berkeley Marina.

They made ideal study subjects, being plentiful and not particularly shy. Unlike migratory populations of the same species, many Bay Area white crowns stay year-round. In a series of articles about California birds, Baptista described this resident variety, Zonotrichia leucophrys nuttalli, as a “bird of the fog belt.” Hopping through the grass, searching for seeds or a spider to give the young a burst of protein, it nests on the ground, or a bit higher in a shrub. It breeds in March, raising young through the summer. By the following spring, the young males have learned the songs they need to seek mates themselves.

Over the years, it became clear to Baptista that birds from different neighborhoods had developed unique dialects within the simple pattern of whistles and trills. In 1981, he wrote to birdsong expert Peter Marler: “In San Francisco, for instance, I’ve found pockets of birds with funny endings. The birds in front of the academy have different introductions than the ones in the back. I visited Alcatraz Island last week; the dialect there is almost identical to that which I recorded at Fort Baker (Marin County), except that Alcatraz birds have developed a peculiar ‘terminal flourish.’”

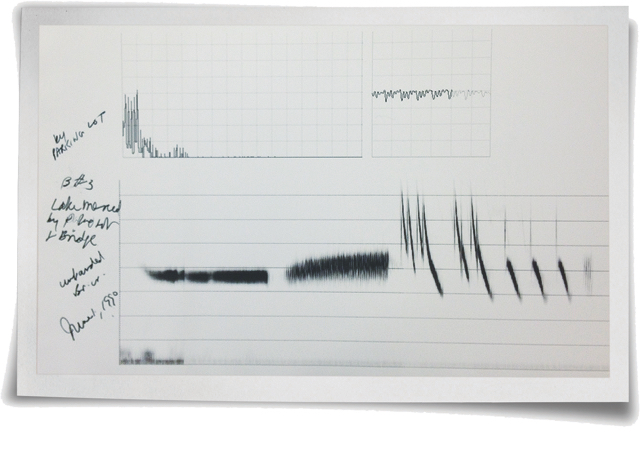

Baptista had a notably keen ear. In addition to speaking five languages, he was able to whistle the songs of individual sparrows. When his recordings were translated into spectrograms (pictures of sound), though, it was easy for even a novice to see that populations had distinct dialects, marking a Treasure Island bird from a Richmond dweller. He labeled the variations: the Lake Merced dialect; the Presidio dialect; the San Francisco dialect, emanating from the city’s noisy core; and so on. He considered many reasons for these variations—a mishearing that catches on because of isolation or an advertisement that a male is local to and fit for a specific meadow or plot of trees. He became fascinated with the “cultural evolution” of song and determined, among other things, that male birds most often learned the song not of their fathers, but of their rivals. Sometimes, he noted, they would even pick up a different species’ tune to do battle, and he recorded white crowns singing the songs of a Lincoln’s sparrow and a strawberry finch.

The sight of Baptista lugging around his huge tape recorder and microphone was soon a familiar one to local bird-watchers and park rangers. Newspapers and magazines fed off his enthusiasm and charisma, referring to him as “Birdman Extraordinaire,” “The Sparrow Man of Golden Gate Park,” “The Man Who Speaks Sparrow,” and “Maestro of the Bird Symphony.” A colleague told The New York Times that Baptista was “the Henry Higgins of the bird world.”

Over the course of his career, he produced more than 120 scientific papers, coauthored The Life of Birds with J.C. Welty, and served as Associate Curator of Ornithology and Mammalogy at the California Academy of Sciences. This reputation was one of the reasons that Luther, in the late 1990s, not long out of college, just back from the Amazon and casting about for a project, wrote to Baptista and asked if he needed help. He did.

Together they recorded birds at the Presidio to see if they were singing the same songs their ancestors had when Baptista put them on tape in 1969-70 and 1990. In the 1970s, Baptista noticed the San Francisco dialect making inroads into the Presidio, and now Baptista suspected the Presidio dialect might be going extinct.

Luther recalls that working with Baptista was as exciting as he’d hoped. “The guy had so much energy, unbounded energy. We’d be talking about something, then all of a sudden he’d just jump up on the table… He would imitate some of the different dialects, and then he’d be waving his arms like he had wings.” Then, Luther says, Baptista would sit back down and calmly suggest they conduct a statistical analysis.

Baptista’s death from a heart attack at 58 in 2000 took everyone by surprise. Luther had been with him just the day before. Baptista had been full of suggestions and plans, handing Luther a manuscript with 30 years of his white-crowned sparrow work and suggesting Luther could use the references, if he needed.

But when Baptista died, Luther left to get his Ph.D. at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, shelving the research and the white-crowned sparrow recordings, unsure of what use they would be now.

Several years later, another young researcher, Elizabeth Derryberry, found herself curious about change in bird songs over time. How and why do calls alter? Would a significantly new song result in evolution as populations became acoustically isolated from one another? To find out, she needed historical recordings to compare with those she hoped to gather. Baptista’s legendary decades of data on white-crowned sparrows seemed perfect, but where were the songs? The Borror Laboratory of Sound in Ohio didn’t have them. Neither did the Macaulay Library at Cornell. Finally, Peter Marler suggested she try the California Academy of Sciences, and hurry, because the old building was set to be torn down.

In 2003, the stately facilities of the Academy in Golden Gate Park were being dismantled, with exhibits from penguins to sea bass and archival insects moved to a temporary site in downtown San Francisco while a shiny new LEED-certified facility was to be erected in its place. As Derryberry walked into the chaos, the iconic Foucault pendulum was coming down. Everyone was busy packing, but Douglas Long, collections manager for the Department of Ornithology and Mammalogy, said she could peek into Baptista’s office and see what she could find.

She was surprised he still had an office, three years after his death. But there it was: an unfinished manuscript on the desk. The clutter of recording devices and field journals. Old reel-to-reel tapes exposed to the sun, causing Derryberry to worry they would disintegrate, if they hadn’t already. “His desk was just like it was when he died,” she says.

Digging through drawers and boxes, she found recordings that had been converted to digital audiotapes (DAT). She called her adviser and crowed, “I found them.”

He replied, “Get them all.”

Less obsolete than the reel-to-reels, DAT was still hard to access. Fortunately, with the help of San Francisco’s ample supply of audio engineers, Derryberry was able to listen to the recordings, convert them, and begin unraveling the mystery of shifting birdsong.

She compared Baptista’s 1979 recordings of male white-crowned sparrows singing at Tioga Pass, just outside Yosemite National Park, to recordings she made there herself in 2003. When she played the newer songs to females in cages, they crouched and shivered their wings, indicating they were ready to mate, almost twice as often as when she played the historical songs. Free-flying males at Tioga Pass responded more aggressively to the current songs than to Baptista’s recordings. The birds had a marked preference for contemporary tunes, demonstrating the way a song’s evolution might create a genetic barrier between populations that would eventually produce new species.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Marin Sparrows Still Sing In Different Dialects

Listen: Bolinas white-crowned sparrow

Listen: Abbott’s Lagoon (Point Reyes) white-crowned sparrow

Listen: Schooner Bay (Point Reyes) white-crowned sparrow

Meanwhile, Ph.D. completed, Luther finally returned to the San Francisco recordings and discovered that, as Baptista had predicted, no one sang the Presidio dialect anymore. He eventually published the work in a paper coauthored with Baptista, but framed it in a way his mentor hadn’t intended, not just looking at the extinction of the Presidio dialect, but the fact that the dialect that outcompeted all the others—the San Francisco—had the highest minimum frequency and was least likely to be lost in traffic noise.

Since the time Baptista charted the birds, San Francisco had shifted. MP3 players replaced eight-track tapes. The Loma Prieta earthquake changed traffic patterns. People came for dot-com riches rather than the Summer of Love. More cars crawled across the Golden Gate Bridge; the city grew measurably louder. Luther and Derryberry documented the increase in noise in a paper for the journal Animal Behavior, where they showed that birds sang the San Francisco dialect at a higher minimum frequency than when Baptista had recorded them in the 1970s.

We don’t often get to see how other species carve up the landscape. But there, in the digital recorder, were boundaries and borderlands, maps of the changing city.

Now Luther and Derryberry, who became friends in a graduate school animal communication class, have joined forces with the support of a National Science Foundation grant to delve deeper. For three summers, starting in 2014, they and their graduate students are exploring sites around San Francisco, learning more about Baptista’s birds.

“It’s amazing how things come full circle,” Luther says.

While Luther watches sparrows attack his speaker in the field, Derryberry conducts complementary experiments in a lab at Tulane University. Recently, her graduate students captured three- to four-day-old white-crowned chicks from San Francisco neighborhoods and whisked them in a van to New Orleans, driving only at night (the baby birds wouldn’t eat in a moving vehicle), staying at motels that allowed pets during the day, and feeding them constantly.

“It’s probably the most involved experiment I have ever done, and stressful,” Derryberry says.

As the male chicks learn to sing, Derryberry and her cohorts will play them high-frequency songs and low-frequency songs along with recordings of urban noise. Will the birds copy the more traditional songs—the low ones—or the songs that are easier to hear—the high ones?

It turns out that raising the minimum frequency, for these birds, may come at a cost. An experiment with great tits in the Netherlands found that females still prefer the low-frequency version, the one not upshifted out of the range of traffic. Males who spent more time singing at higher frequencies are more likely to be cuckolded. So there’s an apparent choice: Be macho or be heard.

Derryberry and Luther aim to see if the white-crowned sparrows in the Presidio face the same choice, if there might be something maladaptive about the new song. She sums up the fundamental question this way. “Is there a trade-off?” she asks. “Are urban males less sexy?”

Some animals have clearly evolved to live near humans, making changes on the level of genes and not just malleable behavior, separating from their more rural ancestors into new, urban species. Not just pets, like dogs, but creatures like the house sparrow, Passer domesticus, a bird that is willing to nest in gutters and parking garages and perch on cafe tables to glean muffin crumbs. Fossil evidence shows house sparrow bones in a cave near Bethlehem, dating from 400,000 years ago, a spot frequented by early humans.

House sparrows thrive not just near people, but in cities specifically. As early as 1869, the article “A Chirp about Sparrows” in the New Monthly Magazine mentions that “the London sparrow is one of the institutions of the great metropolis” and adds that those that “be London born and bred” are particularly pert and voracious. Many observers mention that their sooty, smoky color blends in with the dirty air. They, like pigeons, crows, and starlings, seem framed for city living.

White-crowned sparrows appear to be adapting and evolving in similar ways. Territories in the city are smaller. Comparing plumage with study specimens at the California Academy of Sciences and UC Berkeley, Luther and Derryberry found that coloration on the back of urban white-crowned sparrows is darker, a trait present in many city bird species. No one is sure why, though a recent study suggests the darker feathers store toxic metals, keeping them out of the birds’ bodies and protecting them from the toxin’s effects.

This aspect of Derryberry and Luther’s work, the potential for rapid evolution to a city bird, is the next frontier of urban ecology research, according to John Marzluff, a University of Washington professor and author of the book Subirdia, about the rich avian life—not just house sparrows and pigeons—flourishing in the suburbs. And it makes him somewhat optimistic.

He doesn’t doubt some species will suffer, but he thinks some others may make it, even through the trials of climate change. “If birds are able to adapt in the course of decades to the most inhospitable habitat, where we live,” he says, “it’s hopeful they might be able to handle the other challenges as well.”

The rebuilt California Academy of Sciences is a gleaming monument to contemporary natural history, with a four-story indoor rain forest, a glass room where scientists at work are on display, a cafe featuring platters of local cheeses. Upstairs in the Baptista archives, dozens of boxes trace his interests, from his first notes on bird dialects to feathers bird-lovers mailed him for identification, plans to document a disappearing human dialect from his home island of Macau, and ideas for one of his last talks, about ties between birdsong and music. He includes examples of Mozart composing “A Musical Joke” in imitation of a starling and quail calls in a Beethoven symphony.

In the boxes, letters on embossed letterhead and typed in duplicate give way to Xeroxes, then printouts of emails. The technology changed, just like the recordings, and the museum exhibits, and the birdsongs. But constant through all these details and formats, from species to species, through space and time, is the content of the message: “I’m here. I’m here. I’m here.”