Andrea Mackenzie stands on a dirt turnout, amid a landscape of golden hillsides and gnarled valley oaks. “We’re only ten minutes from San José and yet you feel as if you’re miles away from civilization,” she says. As general manager of the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority, Mackenzie has worked for the better part of a decade to protect large swaths of the imperiled 7,500-acre Coyote Valley, sandwiched uneasily between the sprawl of San José and the rapidly growing community of Morgan Hill. She mentions the valley in the same breath as the Marin Headlands and the Presidio, iconic landscapes saved from development by concerned citizens and responsive leaders. In Mackenzie’s estimation, Coyote Valley is the last major parcel of open space available for protection in the Bay Area, a slice of a vanishing California that are on the brink of receiving the protections that she and others in the environmental community say are long overdue.

For decades developers viewed Coyote Valley as Silicon Valley’s next frontier, a blank slate upon which tech giants such as IBM and Cisco would construct sprawling campuses of glass and steel. (One famous bit of local lore tells of Apple CEO Steve Jobs touring the valley by helicopter, looking for a bucolic setting to build Apple’s headquarters.) More recently, as tech firms including Apple and Cisco have bolstered their presence in and around the urban cores of San Francisco, Oakland, and San José, business leaders have re-envisioned the valley as a hub for online retailers, a shipping mecca of winding arterioles and fortress-like warehouses and distribution centers.

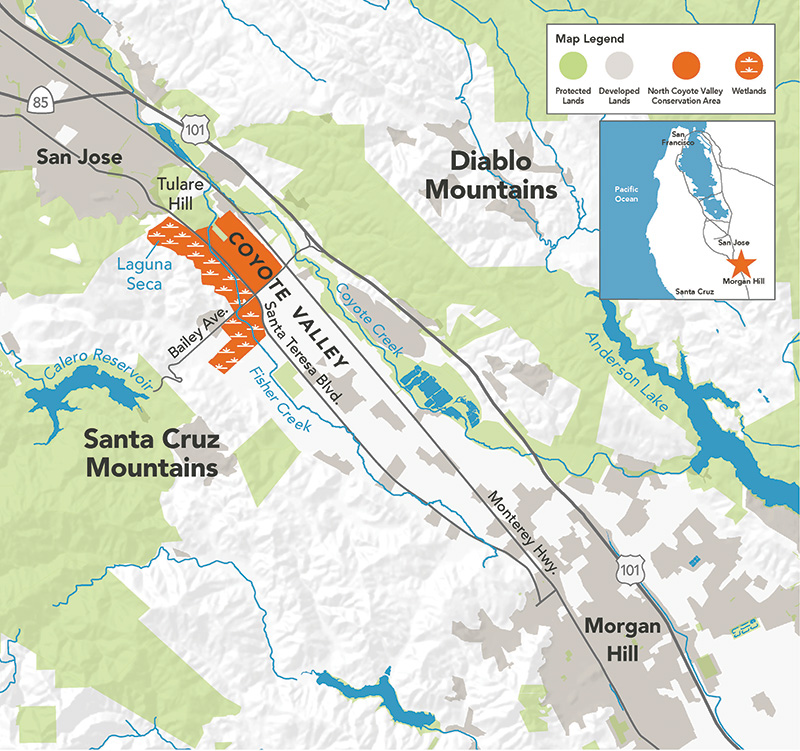

Though South Bay developers and business boosters continue to tout the valley as an important region for growth, the economic benefits of the valley’s environmental resources have come to the fore. Massive flooding in San José in 2017, which displaced roughly 14,000 residents and caused an estimated $100 million in damage, highlighted the need to restore the valley’s once-extensive wetlands for downstream flood control. In addition, valley aquifers buffer groundwater supplies for roughly 2 million residents of Santa Clara County, particularly in drought years. Ecologically speaking, Coyote Valley not only provides critical habitat for rare, threatened and endangered species, including the threatened California red-legged frog and bay checkerspot butterfly; it also supplies a key linkage between wildlife habitat in the Santa Cruz Mountains and the Diablo Range. For hikers, Coyote Valley is a connection between vast open-space parks to the east and west and a southern link in the Bay Area Ridge Trail, which, when complete, will make a 550-mile circumnavigation of the Bay Area.

Earlier this year, California state assemblyman Ash Kalra authored AB 948, which declared Coyote Valley a landscape of “statewide significance” and presented a framework for conservation. San José mayor Sam Liccardo, who has made reducing sprawl and increasing density in downtown San José pillars of his administration, has become an outspoken supporter of conservation in Coyote Valley, touting it as a critical component of San José’s push to curb sprawl and brace for a warming climate. “San José is one of the first cities in the U.S. to invest in natural infrastructure in preparation for climate extremes,” said Liccardo in a press release. “This is a visionary, smart growth approach that will make our communities more vibrant, productive and resilient to climate change in the future.” With last year’s passage of Measure T, a $650 million infrastructure bill that allocated $50 million for open space acquisition in Coyote Valley, San José and Santa Clara County are poised to take possession of roughly 937 acres of wetlands, agricultural land and valley oak savanna.

And yet the ecosystems of Coyote Valley are a mere fragment of what they once were. Major highways bisect the valley. High-tension power lines crisscross the surrounding hillsides. Farms and McMansions squat on vast acreages, further fragmenting remaining swaths of natural habitat. Water engineering projects have altered the natural course of the valley’s streams and the functioning of its wetlands. To make matters more complicated, much of the valley is still zoned for commercial use, meaning that groups such as the Peninsula Open Space Trust and Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority have been forced to pay premium rates for individual pieces of land—parcels that must be somehow stitched together in the years ahead into a cohesive whole.

All of which is to say that preserving the natural attributes of Coyote Valley will require an ecological reimagining as bold and unwavering as the commercial dreams that sought to transform the region for decades. Can it be done—and is it worth the cost?

Getting a sense of what the valley could become means understanding what it once was. That is where Robin Grossinger, senior scientist with the San Francisco Estuary Institute, comes in. Grossinger is well known in Bay Area environmental circles for using old maps and other historical documents to paint a picture of the region before urbanization. Prior to settlement, he says, Coyote Valley was a mosaic of habitats. In the higher reaches, vast swaths of oak woodlands tumbled down into valley oak savanna cut through with ragged serpentine outcrops. In the creek bottoms, groves of willow interlaced with vast meadows and marshlands. This diverse patchwork of biomes provided habitat for dozens of species of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, songbirds and insects. For centuries, it was home to the Amah Mutsun and Muwekma peoples, who hunted for game in the uplands and fished for salmon and steelhead in creeks and streams. There were groves and glades of oaks, which opened up into a massive wetland on the valley floor, Grossinger says. “There was really nothing like it throughout the Bay Area.”

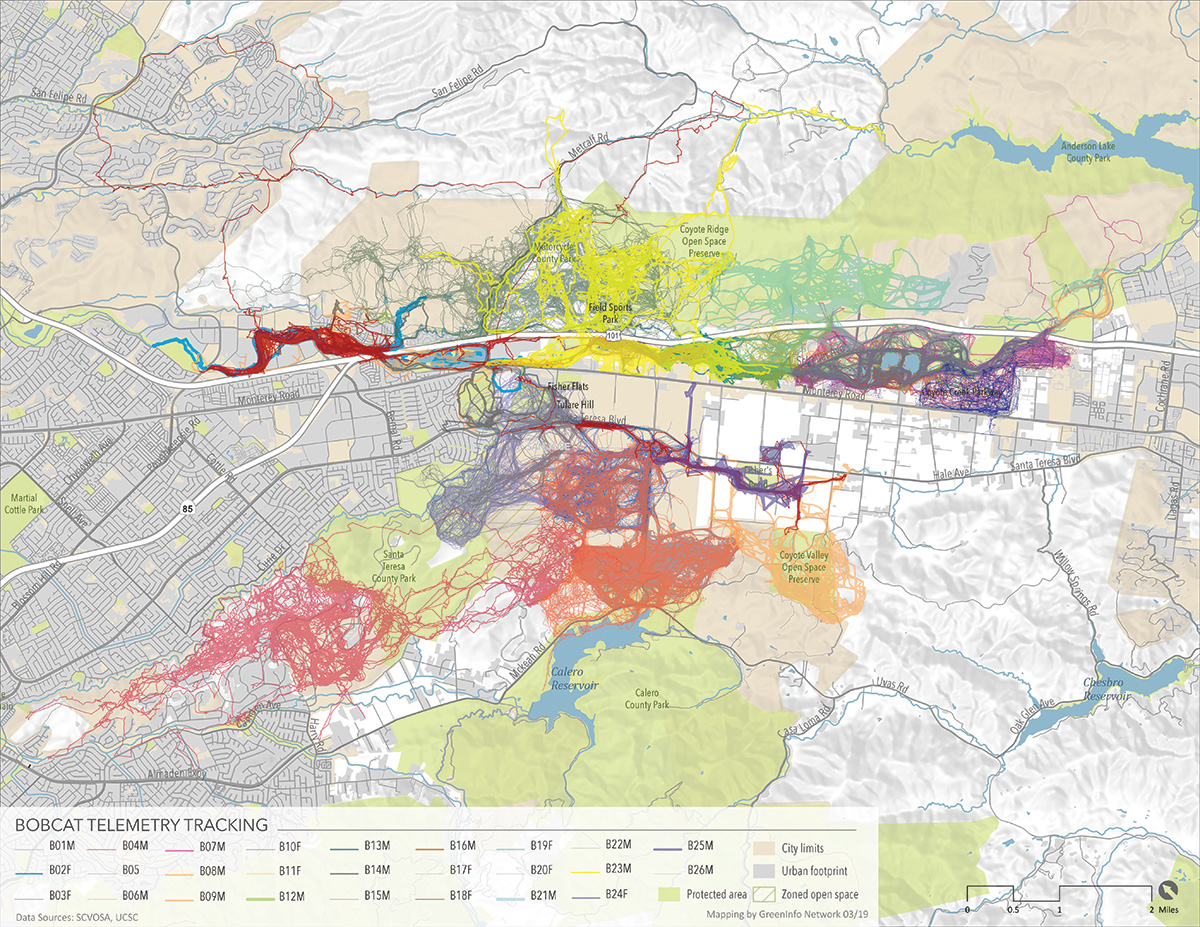

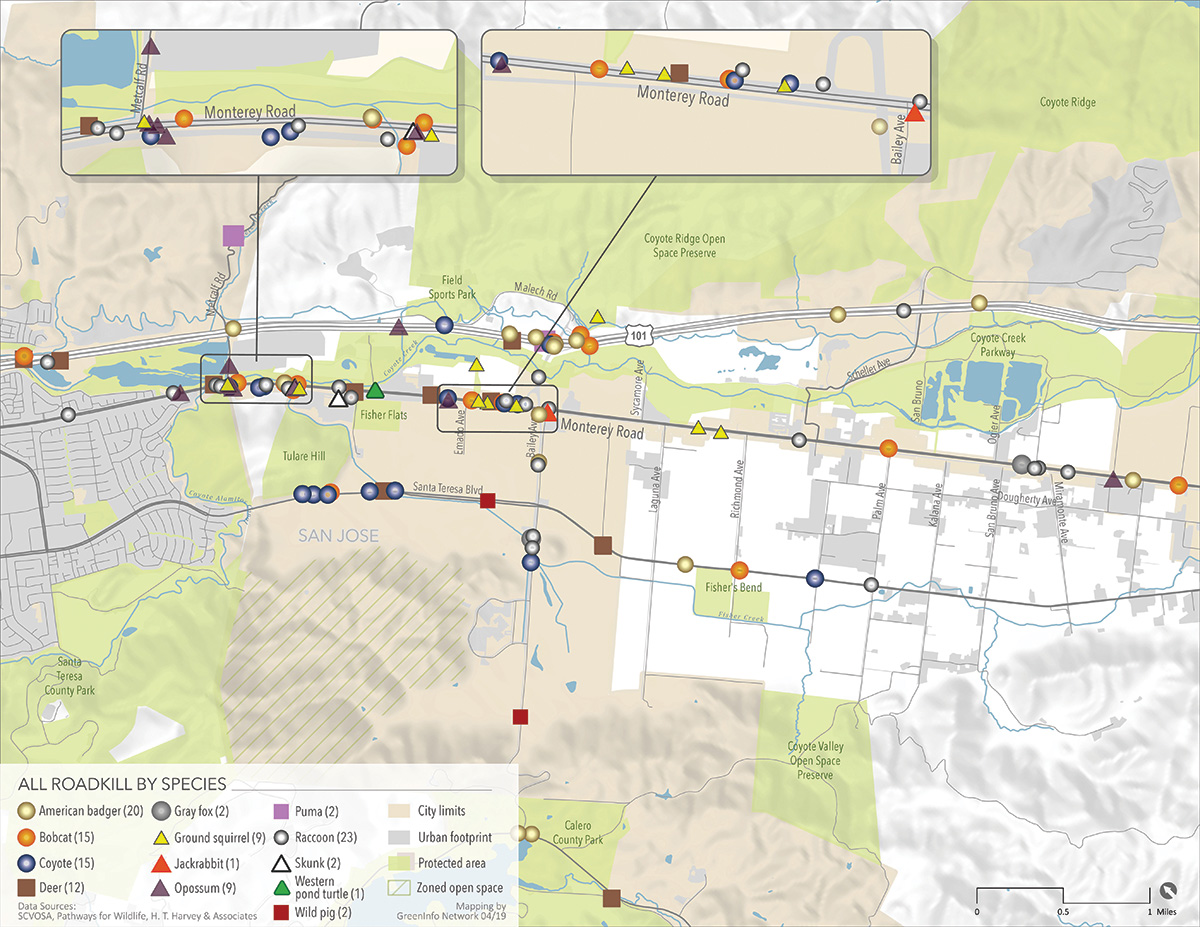

But over the last century, as urban development and farms encroached, the valley’s major habitats have been severely degraded and, in many places, erased entirely. This fragmentation of landscape has had a pronounced effect on the region’s wildlife, says Tanya Diamond, a wildlife ecologist and co-founder of the research organization Pathways for Wildlife. Using motion-activated camera traps, Diamond and her team have mapped several of the valley’s most frequently used corridors. One critically important wildlife thoroughfare lies along Fisher Creek (which Diamond describes as a “wildlife highway”). In spite of the significant alterations, Diamond and her colleagues were astonished by the number and diversity of animals—bobcats, deer, foxes, and coyotes—they documented moving along the waterway. Their data has also highlighted the dangers faced by migrating animals.

To witness firsthand the fraught nature of this journey, I visit a short section of the creek with Andrea Mackenzie and Matt Freeman, assistant manager of the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority. We park at an unmarked pullout on the shoulder of the Monterey Highway and proceed down a rough embankment into a ravine overgrown with weeds and trees. Below the roadbed of Monterey Highway, Fisher Creek flows listlessly through a concrete channel. We skitter down the path and emerged at a square concrete tunnel (known in engineering parlance as a box culvert) scrawled with graffiti. In spite of its urban aesthetic, Freeman notes that bobcats, deer and other species use this tunnel as a means of crossing the valley. “Obviously this isn’t an ideal wildlife corridor, but animals still manage to get through here,” he says. “We can do a lot better to reengineer the streambed to a more natural state, to make things easier for animals to pass through.”

Though Highway 101 and its tens of thousands of cars per day would seem to present the most imposing barrier to animals in Coyote Valley, Diamond says the roadway is actually quite “permeable,” allowing animals to pass in numerous places. However, her team’s data has painted a grim picture for the smaller Monterey Highway, which connects San José and Gilroy. Here, opposite lanes of traffic are separated by a concrete divider topped with a chain-link fence, making it virtually impossible for animals to pass. “Even if [animals] get to the middle barrier unscathed, they’re trapped,” Freeman says, reiterating Diamond’s findings. “Animals such as deer that can jump the barrier often leap right into oncoming traffic.” After Diamond and her team published their findings on roadkill deaths along Monterey Highway, the city of San José placed a wildlife crossing sign along that area. “It’s just a sign,” Diamond says. “But it was also an indication that we’ll be able to work with the city in the years ahead to improve this road for wildlife connectivity.”

It’s not just the animals permanently inhabiting the valley that are affected by roadways. Urban sprawl around the Santa Cruz Mountains has marooned cougar populations, cutting them off from the larger cougar populations in the Diablo Range (which is contiguous with the vast expanses of the southern Coast Ranges), hence curtailing their chance to reproduce and ensure genetic diversity. This reproductive isolation could be alleviated, says UC Santa Cruz environmental studies professor Chris Wilmers, by giving populations a more direct connection with one another.

For more than a decade, Wilmers has been studying the impacts of urbanization on the population of mountain lions in the Santa Cruz Mountains. He says there are two critical pathways for the big cats out of those mountains. One is in the southern reaches of the valley, near the town of Aromas. The other is the northern Coyote Valley. To date, none of the animals he’s studied has successfully migrated out of the mountains. In order to make these connections viable, Wilmers says, key pieces of habitat need to be restored in order to provide animals with greater cover: “In the Coyote Valley there needs to be land preservation and land restoration,” he said. “Without these improvements in connectivity, or [without] physically moving animals around on the landscape, the population just won’t be viable over the long term.”

Grand gestures, such as the recently announced $87 million animal “land-bridge” that will span ten lanes of Highway 101 near Los Angeles, may be years off in Coyote Valley. Yet smaller fixes, such as retrofitting culverts along with strategic use of directional fencing, can greatly reduce animal mortality by helping to funnel wildlife toward crossings, Diamond says: “A few targeted changes can really make a huge difference for wildlife.” Still, even these modest changes will not come cheap. A 2017 estimate for improving the Fisher Creek culvert for wildlife passage puts the cost at around $1.5 million.

The reengineering of Coyote Valley’s waterways has impacted not only wildlife but hundreds of thousands of San José human residents and their homes over the years. Early plans for development entailed eliminating the vast wetlands that covered hundreds of acres along the valley floor by installing dikes, levees, and concrete raceways, as was the norm for the era, to divert water from wetlands rapidly into local waterways. These engineering schemes reduced the amount of water naturally permeating back into aquifers and greatly increased flood risk in communities downstream.

And yet large tracts of valuable wetlands still remain in Coyote Valley. A 2017 report from the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority found that that there are over 2,500 acres of open wetlands, which are important in retaining precipitation and mitigating flooding for communities downstream. “This is natural infrastructure,” Mackenzie says during our visit, gesturing to a conspicuous depression called Laguna Seca, the centerpiece of the plan for rejuvenating the wetlands of Coyote Valley. “This landscape is contributing to the resilience of the entire South Bay region.”

Before the Santa Clara Valley was settled, Laguna Seca was a dynamic and ever-changing landscape, Grossinger says. “It would expand and contract each year, but the core area of wetland was perennial and hundreds of acres in size.” Wetlands of this size and complexity are rare in the Bay Area, he adds: “Laguna Seca is the only one that wasn’t completely developed.” And today Laguna Seca is roughly ten percent of what it was. Grossinger and his colleagues at the San Francisco Estuary Institute unearthed a trove of documents from the early 1900s that illustrate the lengths the city and county have gone to—dredging the wetlands, burning the resulting dry vegetation, tilling the soil in a failed bid to introduce agriculture—in order to engineer Laguna Seca out of existence. “It’s an amazing chronicle of destruction,” Grossinger says.

And yet even though extensive engineering will be necessary to return Laguna Seca to its former glory, it remains the largest wetland in the South Bay. “This is a feature that has resisted all efforts to eliminate it,” Grossinger notes. During our visit in mid-July, it was little more than a pasture. In the basin below, cows grazed on a lush carpet of green grass. But following heavy winter rains, the dry lakebed transforms once again into a massive marsh, teeming with cattails and a rich array of bird life. In this watery state, Grossinger says, it also serves a vital hydrological function, impounding millions of gallons of water during heavy rains, which is kept out of Coyote Creek and away from downstream neighborhoods in San José. “It feels like a system that is ready to come back.”

Restoring Coyote Valley to some semblance of its earlier self will be not just a complex engineering task, but an expensive one. The Open Space Authority along with the City of San José and the Peninsula Open Space Trust are currently in the first phase of land acquisition, negotiating with two prominent development companies to acquire 937 acres of key parcels out of the larger 7,500-acre area. According to Marti Tedesco, the chief marketing officer for the Peninsula Open Space Trust, the per-acre price of land in Coyote Valley pencils out to roughly $100,000 per acre.

The biggest and most expensive piece of the puzzle is the 570-acre site abutting the intersection of Bailey Road and Monterey Highway. In 2016, Brandenburg Properties purchased the property from Cisco for an estimated $15 million, according to the Silicon Valley Business Journal. Though the numbers aren’t yet final, at current land rates the property stands to fetch $37.5 million—a $22.5 million profit funded largely by local taxpayers. “Yes,” Tedesco wrote in an email, “they do indeed stand to profit from this sale.” According to Tedesco, POST tried unsuccessfully to acquire the Cisco property the same year it was purchased by Brandenburg. (Though Tedesco would not disclose the terms of POST’s original bid, she said the previous property owner, GKK Coyote Owner LLP, a Delaware-incorporated holding company, may have used POST’s initial bid to shop the property to other buyers.) “It must be added, though, that Brandenburg removed tens of millions of dollars of previous debt encumbrances when they purchased the property in 2016, thereby increasing its market value.”

“We’re paying [Silicon Valley] prices for conservation; that’s just what we have to do,” Mackenzie tells me as we stand overlooking the margin of a parcel owned by a tech company called Xilinx, a short distance from a sprawling campus owned by IBM. Ironically, she notes, the sweeping and mostly unrealized commercial plans for the valley are precisely the reason that large sections of the valley remain intact. And it is that relative lack of development that gives Coyote Valley its intrinsic value—even though that value can be hard to define. “Part of the tension and challenge is quantifying the costs of this landscape,” Mackenzie adds. She mentions a recently passed $2.5 billion flood control bond in Houston, Texas, of which nearly one-sixth will be spent on purchasing the land and removing houses and other structures from floodplains. “It’s so expensive and it uproots people’s lives when you have to go back later and undo the damage,” adds Marc Landgraf, external affairs manager for SCVOSA. “Here we have the opportunity to do it right in the first place.”

But the land is no blank slate. Managing the proposed Coyote Valley preserve will involve juggling a host of uses not typically associated with open space. For example, Mackenzie says, agriculture will have a role to play. Farms in Coyote Valley currently account for around 30 percent of a $1.6 billion agriculture industry in Santa Clara County, and well-managed farmland can not only bolster the local food supply but also act as a buffer to reduce flooding, sequester carbon, and mitigate sprawl. As Mackenzie sees it, the substantial price for the land—not to mention the work necessary to restore and manage it—is worth it. “This is a last-chance landscape,” she says. “We need to make sure we do everything in our power to protect it today or we could lose it forever.”