This year the East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD), the nation’s largest local park district, celebrates its 75th anniversary. Citizens of Alameda and Contra Costa counties can be justly proud of this extensive park system, covering 98,000 acres in 65 parks and preserves and providing recreational facilities, open space, scenic views, and wildlife protection in the midst of millions of people.

Regional parks stretch from San Francisco Bay to the Sacramento Delta and from the Carquinez Strait to Sunol. They extend along the spine of the Oakland-Berkeley Hills all the way to Union City and Pleasanton, hug the Bay shore from Fremont to Richmond, and grace the banks of the river from Martinez to Antioch.

The East Bay parks have served so many, so well, for so long that one might be inclined to become complacent, imagining that their future is secure. Nevertheless, the welfare of parks in California is by no means assured, as evidenced by the fate of the state parks, now threatened by closure due to budget cutting.

The question is whether the East Bay Regional Park District can cope with the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse bearing down on California: fiscal crisis, population growth, urban sprawl, and climate change. Keeping them at bay will require adequate funding to maintain and expand parklands; the capacity to serve a burgeoning and changing public with many competing demands; an ability to wrestle with the exploding metropolis of the Bay Area; and a sufficient response to the ecological pressures wrought by a shifting climate.

The Bucks Start Here

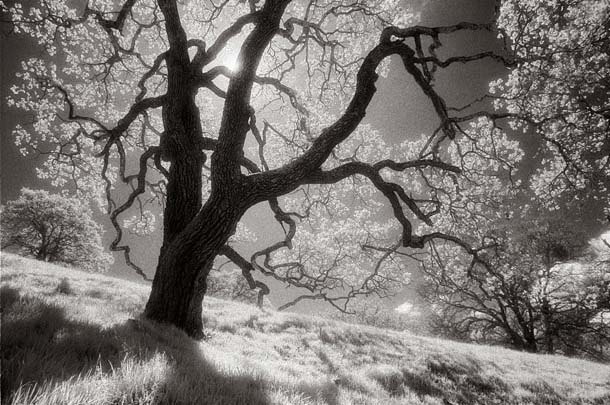

- SECOND PLACE Bill Helsel: Oak tree, Briones Regional Park

- Marc Crumpler: Mount Diablo from Round Valley Regional Preserve

- Rick Lewis: California clapper rail, Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline

- John Krzesinski: Pleasanton Ridge Regional Park

The financial base of the district is sound, thanks to the long-standing support of the citizenry. “Parks are a core value in the East Bay,” says Bob Doyle, assistant general manager for land acquisition. Voter approval of Measure WW in 2008 provided $500 million in capital bonds to fund land purchases, park upgrades, and trail extensions for years to come. A quarter of the money goes to grants for cities in the district for municipal parks.

Last fall’s ballot measure passed by a whopping 72 percent of the bi-county electorate, despite the worst economic meltdown in three quarters of a century. This is the same supermajority East Bay voters gave the measure that created the district in 1934 in the midst of the Great Depression. Neither victory was inevitable. After all, the cities of Oakland and Berkeley had failed in creating parks during the booming decades of the early 1900s.

Measure WW repeats the success of Measure AA, approved in 1988 for $250 million in bonded debt. The latter allowed for a huge increase in parklands–about 30,000 acres–in the last years of the 20th century. District managers nearly doubled their capital by using complementary funds from the state’s Coastal Conservancy, grants from state park bonds, and development offsets.

Despite its recent victory, the park district, like agencies across California, is facing budget cuts because the state is dipping into local tax revenues. A bigger problem may be the overall decline in property values, which determine the taxes the district receives. “That’s what funds all the parks,” says Doyle. “It’s fantastic that we have capital for acquisition and restoration, but we can’t open new parks without funding for operations.”

Nonetheless, the success of Measure WW proves that the park district still has a solid base of support, including conservationists at the Sierra Club, local Audubon chapters, Save Mount Diablo, and more. Activists have worked closely with the EBRPD to safeguard open space, but also pushed it in new directions when necessary, such as moving to bayside parks, saving Pleasanton Ridge, and floating the 1988 bond measure.

Parks For (and By) the People

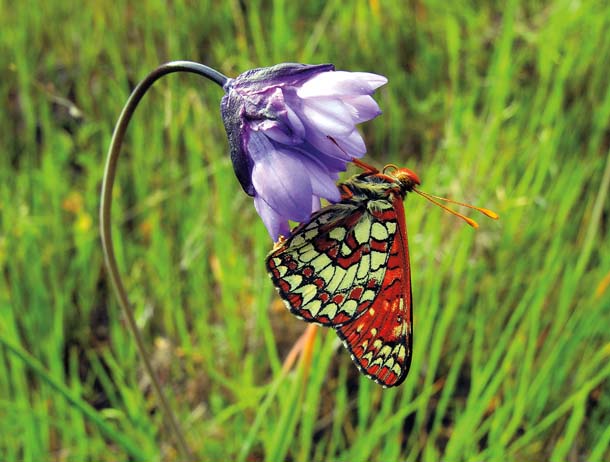

- Deane Little: Checkerspot butterfly on blue dicks, Sunol Regional Wilderness

The idea of public parks has evolved over time and the mandate of the regional park district has expanded along with it. Accessible outdoor recreation was the first order of business for the original parks in the Oakland-Berkeley Hills (Tilden, Sibley, Redwood), and recreation remains at the heart of the district’s mission. The East Bay parks include such notable swimming and fishing sites as Lake Anza, Del Valle, Crown Beach, Shadow Cliffs, and Quarry Lakes. The parks offer over 4,000 picnic tables and 200 campsites, and they include such attractions as the farm at Ardenwood, the steam train at Tilden, and the historic Black Diamond Mines.

- Karl Gohl: Mission Peak Regional Preserve

The parks are meant to be used and they are, visited 14 million times every year by people from all over the Bay Area. Not surprisingly, those who use the parks are far more likely to support park financing than those who do not–80 percent versus 52 percent. Changing demographics are not undermining support for open space: District polling shows that African-Americans and Asian-Americans voted in higher percentages for Measure WW than Euro-Americans, and Latinos only slightly less.

Accessibility is a key word. The district’s stated goal is to have a park or trailhead within 10 to 15 minutes’ drive of every household in the East Bay. A Parks Express program offers low-cost charter buses to groups serving disadvantaged children, low-income seniors, and people with disabilities. In the wake of initiatives pushed by Hulet Hornbeck in the 1960s, the district also has one of the most extensive trail systems in the country, over 1,150 miles in all.

The district’s mission has changed along with its geography. From an original conception of a chain of woodsy hilltop retreats for the urban masses, the district shifted gears in the 1960s under General Manager William Penn Mott Jr. to embrace wide-open grassland parks (Briones, Wildcat Canyon, Garin) and bayside parks (Crown Beach, Coyote Hills, Point Pinole). It was Mott who first emphasized the district’s interpretive programs, carried out by one of the nation’s largest regional park naturalist staffs.

In the 1970s, more emphasis was put on staying ahead of urban sprawl. Under Richard Trudeau, the district took a great leap east toward Mount Diablo (Black Diamond, Morgan Territory, Diablo Foothills) and the Delta (Brown’s Island, Big Break) and expanded dramatically to the south in the Tri-Valley area (Tassajara Ridge, Bishop Ranch, Del Valle) and the Diablo Range (Sunol, Mission Peak, Ohlone).

Today, district managers keep pushing eastward, where new urban growth is greatest. Creating parks in places like Concord Naval Weapons Station and Deer Valley on the eastern slope of Mount Diablo will be essential to serve future generations. At the same time, a critical target is the inner East Bay from Richmond to Hayward, where the city is densest and the people have the least resources. Here the parks must juggle an array of competing demands, from recreation to habitat protection. This is also where sea-level rise due to climate change threatens parks and millions of dollars’ worth of wetlands restoration.

Balancing all these variables is no mean trick. “It’s a Rubik’s cube for the staff,” acknowledges one manager. An acute case is the new Eastshore State Park, managed by the district for the state. On this bare sliver of 80 abused acres between the Bay and I-80, a multiple-use park is gradually taking shape, with biking trails, ballparks, boat launches, and restored coastal vegetation.

Those competing demands, however, have helped the district step up to the plate on critical fronts. It is not just farsighted managers who have brought the park system to its present state, but activists who refused to give up on their vision–people like Bob Walker and Mary Bowerman fighting for Mount Diablo or Jean Siri and Norman LaForce along the East Bay shore.

Regional Powerhouse

For decades, the East Bay has faced pressures from suburban expansion. The I-680 corridor is now the central spine of the region and eastern Contra Costa County is no longer predominantly rural. Thanks to the financial bubble, growth got out of control over the last decade, with sprawl quickly consuming farm-land.

In this urbanized environment, parks and open space have become a means of delimiting and directing urban development. As General Manager Pat O’Brien observes, “Without our parks, the East Bay would look very different.” He should know: The park district is now the largest single landowner in the East Bay and a formidable force in the halls of local governments overseeing land use decisions.

The district’s full-time planning unit not only looks ahead to future parkland but looks over the shoulders of city officials. This sometimes requires dramatic action, as when the district used eminent domain to seize Breuner Marsh in Richmond from a developer who planned to build nearby.

When it comes to land use in the East Bay, the park district is the most important player in the game: The district has the weight to keep open space protection on the table every time.

But with power comes the impossible task of keeping many contending interests happy. Mountain bikers, frustrated that more trails aren’t open to them, mounted some of the most visible opposition to last year’s park bond. Other activists want the district to do more to limit cattle grazing and recreational use in sensitive areas, which can lead to habitat degradation for rare species.

The Web of Land

What stands out on a map of open space in the greater East Bay is that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The park district is only one actor among many in an immense web of parks, watersheds, and other protected areas. But it is at the center of the web and pivotal in regional land management.

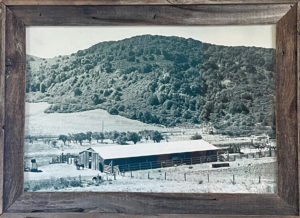

Regional thinking about land conservation began with the 1933 Olmsted-Hall report that served as the district’s blueprint. It foresaw today’s chain of parks and trails that run along the East Bay Hills, down creek channels, and along the shoreline. A ridge trail from the Carquinez Bridge to Fremont is part of that vision.

Over the last generation, conservation biology has brought a sea change to open space management, with its emphasis on protecting whole ecosystems. Out of this came the idea of open space for nature’s sake, including wildlife corridors, daylighted urban creeks, and restored marshes. “We’re looking not for a map dotted with preserves, but a map with a network or web of open space,” says Save Mount Diablo’s Seth Adams. “We in the Bay Area are at the forefront of that idea.”

With good reason. The East Bay, particularly Mount Diablo, is one of four biodiversity “hot spots” in California, itself the most diverse region in the continental United States. “There are many ‘last great places’ left, right here in the East Bay,” remarks Adams, putting a new spin on the words of David Brower.

The park district pays close attention to habitat stewardship. Staff biologists oversee grazing practices by ranchers who lease grazing rights, and they carry out detailed studies of wildlife. As a result of such practices, native grasses, red-legged frogs, falcons, and other organisms have rebounded in protected areas.

But climate change makes everything more complicated. Wildlife in the interior will face hotter summers, longer droughts, and more wildfires. Shoreline areas will see marshes and trails threatened by rising sea levels. “All those things are going to be a huge challenge,” says Doyle. “It’s not going to stop the public from enjoying their parks, but we’re an agency that places a high priority on native species, so it’s a big concern for us.”

Future People for Open Space

People, too, benefit from open space that gives them more breathing room. New parks at the eastern edges of the metropolis will prove ever more vital as the city expands and generations to come seek solace in nature nearer their doorsteps. With global warming, we should revive the dictum of Frederick Law Olmsted, father of American parks, that parks are “the lungs of the city.”

Education to ensure that people understand the benefits of open space is another essential function of the East Bay parks. Working with schools is a big part of that, with students taking field trips to the parks and park naturalists going into classrooms. “We aren’t just teaching about butterfly biology and who eats what snake,” says longtime chief naturalist Ron Russo, now retired. “The naturalist staff and student aides also serve as a front door, introducing people to what the regional parks are all about.”

Central to that role are the nine visitor centers spread across the system, from Tilden to Coyote Hills. Another is in the works at Big Break near Antioch, as are a “visitor center on wheels” and a traveling aquarium. Every year, more than 500,000 people visit the district’s nature centers or take part in naturalist-led programs.

Facing threats both fiscal and physical from the state budget crisis, urban growth, and climate change, the East Bay Regional Park District will not be entirely spared by California’s Four Horsemen. Nevertheless, the agency is in remarkably good shape and aging gracefully. All signs points to it staying healthy for generations to come, because district leaders, park lovers, and the people of the East Bay are alert to the dangers–and the opportunities–ahead.

.jpg)