Last December I ascended Pedro Point in Pacifica with Catherine Chang, mostly looking for mushrooms. We hadn’t had much rain so didn’t expect full-on mycological glory, but Chang was consoled by the prospect of lichens. Stopping short on the trail, she declared, “Festuca californica, right in front of us!” I looked around for some seemingly invisible circus. Her attention was trained on a plume of delicate blue-gray leaves I would have tromped right past. To the initiated, the sight of a native grass like this growing among exotics is cause for celebration. “It doesn’t have much competition here,” she noted, brandishing her smartphone and taking its picture. Soon we stopped to examine a dead branch crowded with a tangle of delicate light green, dark green, and oxblood webs—a color bomb of multiple textures. “Together they create a landscape,” noted Chang. Now, who ever thought about lichens that way?

A few hours with Chang and her keen attention and deep knowledge kicked my sense of this familiar landscape into 3-D. My eyes were bugging out. I was humbled by the complexity I so frequently and easily overlook. And yet it’s only in her spare time that Chang—a landscape architect by day—has accumulated so much insight into the natural world. She is an amateur, fulfilling that word’s Latin root: amare, to love. In this she exemplifies what might be called a revival in the age-old practice of the naturalist.

Signs of Life

Homo sapiens have been entranced with observing and documenting nature since we became a species, but the term naturalist generally refers to the 19th-century heyday of amateur discovery. During that time, in America and Europe, tens of thousands of botany enthusiasts, birdlovers, and butterfly hunters joined societies and clubs dedicated to their subjects. The outdoors was a place of adventure and community for these people. But as the 20th century progressed, academic science along with state and federal agencies like the U.S. Forest Service increasingly claimed provenance over the natural world and dictated professional protocols for how to understand it. Naturalists and the types of knowledge they pursued vastly declined.

Today, however, we are seeing a resurgence in the observational practice of the naturalist. Not just in the Bay Area, but all over the globe, people like Chang are reconnecting with nature for personal reasons and to help augment what we know about the myriad denizens of the planet. Today’s nature nut is likely to be at least partly driven by an awareness that was just dawning in the 19th century and is reaching something of a desperate pitch right now. Earlier this year an unprecedented scientific consensus was published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), an independent intergovernmental body. The report called out “nature’s dangerous decline” and warned that species extinction rates are accelerating—currently, up to one million species are threatened with extinction.

As the natural world is in many ways unraveling, part of the trouble is our lack of connection with and appreciation for how it works. Luckily, we have plenty of eyes and new tools for taking a fresh and productive accounting of nature. This past April, for example, thousands of people representing 159 cities and every continent but Antarctica, documented their local biodiversity during the City Nature Challenge 2019. Together more than 35,000 participants made more than 963,000 observations of species in nature, using technology to augment the age-old quest to see what’s out there.

Back to the Future

Contemporary naturalists have much in common with their historical predecessors, but there are epochal differences in their aims and approaches. The 19th-century naturalist was contributing to a heady expansion in the store of Western European knowledge. Today’s naturalist is still focused on revelation: of an approximate 10 to 12 million species on earth, only 1.2 million have been named by science. But yesterday’s naturalists had their eyes trained on what they thought was a fixed universe and were motivated by a wish to better understand God through His works. Today’s naturalists may find transcendence in nature but understand this within a context of accelerated change. As ecosystems are highly impacted by the engines of global development, naturalists today are frequently seeking to help create a better understanding of what’s at stake—not so much investigating how God put this world together, but how human activities are taking it apart. Today’s naturalists are aided and abetted by smartphone technology and training programs like UC California Naturalist Program. In the Bay Area we are particularly blessed with opportunities to learn more and do more for nature. Bioblitzes—in which people make nature observations in a particular area for a set time period—have become a favored outreach tool at local parks and preserves. Institutions like the California Academy of Sciences offer regular monitoring projects and invite participation. Myriad volunteer opportunities include seasonal bird and butterfly counting expeditions near home.

Paradise Lost

The Judeo-Christian tradition is often decried as creating a fatal delusion for humankind, ranking us far above the lowly beasts of the earth, and yet the first European forays into understanding nature were religion-inspired. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Christian monks trying to parse what exactly happened to the biblical Garden of Eden sent expeditions to far-flung places to bring back pieces they thought must have been scattered after the Fall. These were organized by relationship in plant beds, dirt-based analogues to today’s digital databases. Faith and facts were deeply entwined in a system of reference resembling the model of an encyclopedia. In the 1700s, Carl Linnaeus established the binomial system of naming still used today to sort out relationships among species, establishing an eventual platform for studying evolution. As the Age of Exploration, when Europeans began traveling the globe in search of trade routes and wealth, expanded the world’s horizons, Linnaeus’s spreadsheet became critical for grappling with an avalanche of discoveries and helped to make sense of them.

By the 1800s, industrialization had provided at least some people with the novelty of free time, and tens of thousands of amateur naturalists charged forth into nature. A growing number of middle- and upper-class ladies and gentlemen traipsed with enthusiasm and nets into meadows and fens, husbanding their quarry in the curiosity cabinets that were common in Victorian homes. The distinction between “amateur” and “professional” was blurry in those days, even as new institutions like the California Academy of Sciences were being established to better codify and understand life on earth. The Academy was founded in 1853 by a group of men, many of whom had medical degrees but were not biological scientists. The business of creating a collection of specimens proceeded in a hodgepodge way. At an early meeting, Dr. Albert Kellogg furnished a living owl, “caught near Point Jackson on San Francisco Bay”; at the next meeting it was reported “that the owl was lost.” The general public contributed specimens as well. In 1854 a Mr. W. J. Steene “presented a curious specimen of cabbage.” At the same time, it was widely recognized that although much of the “new world” had been traversed by Europeans, the unique topography, flora, and fauna of California were revealing a new set of wonders to add to the store of general knowledge. The towering figures in botany at the time, including John Torrey, Asa Gray, and eventually Willis Jepson, maintained vast networks of laypeople with whom they regularly exchanged information and physical materials. The comprehensive surveys they produced would not have been possible without the contributions of an army of naturalists who took an equal interest in what the botanists were doing.

Creatures Great and Small

Many 19th-century nature-seekers wanted to improve their souls by investigating God’s revelation in plants and animals. Going out and collecting, for many, was an act of piety and self-improvement. Ironically, the work of perhaps the ur-naturalist of all times, Charles Darwin, dealt a crippling blow to the project of the amateur with the publication of his 1859 book On the Origin of Species. Demonstrating that, in fact, life forms don’t issue from a spiritual ideal but from generations of reproduction and gradual change, Darwin excused God from fieldwork.

The rise of professional science coincides with the percolation of Darwinian ideas through study of the natural world. To “prove” evolutionary mechanisms, scientists turned increasingly to experiments and away from field observation. They also sought to purge science of inherited belief and excluded stories like Genesis from consideration. By the beginning of the 20th century, academic science was consolidating its authority and separation from other kinds of institutions, particularly the church. Now competing for status and pay, professional scientists laid claim to special knowledge. Despite the fact that hobbyist birders, for example, began avidly cataloguing observations that currently fuel databases like eBird, the tradition of the amateur naturalist mostly faded from view. That is changing today.

Newt Beginnings

Last December I sojourned with Constance Taylor and Ken-ichi Ueda up South Park Drive in Tilden Regional Park. The regional park district prohibits cars on this stretch of road from November to March to protect the seasonal migration of the six-inch California newt, which lumbers along on rubbery appendages, headed to breed in Wildcat Creek, and would otherwise itself be smushed under rubber. We moved slowly, as if we were newts ourselves, leaf by leaf, transfixed by mushrooms, lichen, hawks, and songbirds in the winter landscape. Ueda and Taylor frequently recorded their observations in notebooks and on smartphones.

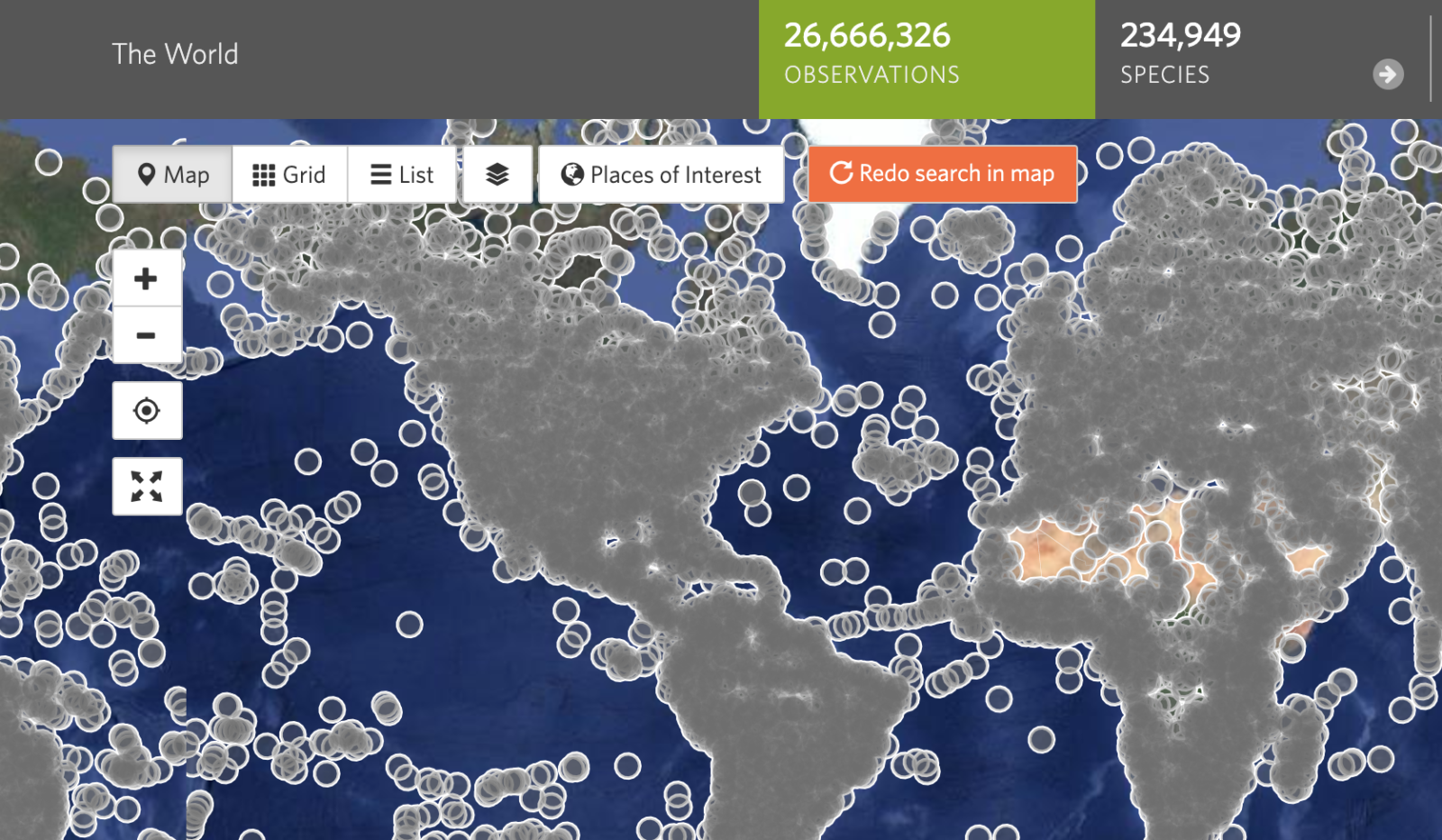

Ueda is one of the creators of the web-based platform iNaturalist, which he co-directs at the California Academy of Sciences with Academy scientist Scott Loarie. Users upload photographic and/or audio observations of nature to the platform; these are then vetted by other users for identification and eventually uploaded to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, a clearinghouse of digital natural history observations in use by scientists and natural resource managers all over the world. iNaturalist joins platforms like eBird that are essentially taking Linnaeus’s format digital. “iNaturalist hangs its observations on the tree of life first organized by Linneaus,” Loarie explains. “We’re using the taxonomy he provided, building on a structure that’s already there. The scientific use of our data is in the areas of biogeography and conservation. With it people can ask the fundamental questions of natural history: what do species look like, and how are they changing?”

Alive in the Anthropocene

Another distinguishing feature of the 21st-century naturalist is a willingness, even an eagerness, to explore nature in less than pristine settings. Damon Tighe works on behalf of the mostly Oakland-focused California Center for Natural History, which Taylor co-founded. Once part of the team that sequenced the first whole genome of a single cell, he now, in his day job, helps educate teachers about tools they can use with students to take DNA samplings, for example, in the field. Tighe exemplifies a “maker” spirit in some of today’s naturalists, who not only observe nature with pencil, paper, binoculars, and smartphones, but experiment with building their own tools of perception. With CCNH he has made a series of pop-up aquariums at Lake Merritt (you read that correctly), showcasing to passersby the variety and strangeness of many things just below the surface.

I spent an afternoon walking around Lake Merritt with Tighe, who commented that “it really should be a national heritage site,” because in 1870 the tidal lagoon was designated the first wildlife refuge in the United States. Today, Lake Merritt is refuge for human life as well, with homeless encampments tucked into the built structures around it. Tighe called Lake Merritt an “Anthropocene environment” because the lake is full of introduced species, brought in by the ballast of ships from all over the world. “A lot of the native species are gone and the invasives have stabilized,” he says. “At the organism level it reflects the human community around it—people from all over the world—in a working, social environment.”

Deep Things Out of Darkness

Taylor, Tighe, and Ueda may seem light-years away from Philip Henry Gosse, who in his 1853 bestseller A Naturalist’s Rambles on the Devonshire Coast mused that the sea anemone evidenced God’s love, since “the exquisite tints with which they are adorned are the pencillings of his almighty Hand. Yes, O Lord!” Gosse motivated thousands to look into the tidepools not only to ogle God’s artistry, but to refine their own souls to better earn His grace. A quest for self-improvement and transcendence is perhaps not as evident in today’s naturalists, who typically aren’t looking for God, per se. But they are keenly interested in understanding an infinitely complex system that is threatened and vulnerable—and in finding solace and deep self-development by engaging directly with nature.