Joseph Engbeck is the author of a celebratory history of California’s state parks. His book starts with 1864 and ends in the 1970s, when the system had grown to 250 parks and was in its heyday. He has intriguing tales to tell about most any era–but falls silent when asked about the one we’re living through now. “I wouldn’t like to write that chapter,” he says.

That’s understandable. California’s world-class collection of parks–protecting spectacular forests, deserts, beaches, mountains, and historical monuments–has suffered from budgetary neglect for decades. In the last six years alone, taxpayers’ contribution to the parks’ operating budget shrank by 37 percent. Poorly maintained facilities, reduced schedules, and short staffing are not unusual. Parks where professional naturalists and educators once guided visitors are now often staffed in “drive-by” fashion, with a single pistol-packing law-enforcement ranger assigned to watch over several parks. “I have nothing but compliments for how they’ve managed to stretch and stretch, but you can only go so far,” says Bob Doyle, general manager of East Bay Regional Park District. “They are basically down to a less than bare-bones police force.”

When the governor and legislature delivered the latest insult last year, a cut of $22 million over two years, the state Department of Parks and Recreation decided to close 70 of its 279 state parks–25 percent of the system–in the hope of minimizing harm to the other 75 percent.

- Robert Hanna opposing closure of Benicia Capitol SHP, kayakers at Tomales Bay State Park, Young supporters of state parks at Big Basin. Credits (L-R): Joan Hamilton, Diane Poslosky, California State Parks Foundation.

- View from the Rocky Ridge trail at Garrapata State Park, south of Carmel. Photo by Julie Kitzenberger.

Since the closures were announced in May 2011, park lovers have rallied, ardently, to keep parks open. At the state’s invitation, nonprofits and government entities have submitted temporary rescue plans. In articles that follow, we chronicle some of their remarkable accomplishments at a sampling of parks around the state.

This article looks at the parks crisis more broadly, from the viewpoint of the state parks department and its allies. In some ways, it’s a confounding Alice-in-Wonderland tale in which “open” can mean closed, “closed” can mean open, attempts to “cut spending” could cost the state dearly, and “saving” a park can mean keeping its creaky gates unlocked for just one more year. But the story is also about the creative part of the chaos: a potentially game-changing 21st-century partnership between the state parks and the people.

In an era of shrinking support for public services, from college education to in-home services for the elderly, parks are expected to share in California’s budgetary pain. If many park advocates have taken the matter personally, it’s because state parks are more than just a department in Sacramento. They are part of a system created by private citizens. In the 1920s the nonprofit Save the Redwoods League worked with landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to survey the state and poll its people. They put together a plan that included the protection of such iconic landmarks as Mount Diablo, Mount Tamalpais, and Point Lobos, as well as redwood groves and popular beaches. Though the state still had vast open spaces and only 5 million people, a $6 million state park bond issue passed by almost 3 to 1 in 1928.

- Limekiln Falls at Limekiln SP south of Big Sur. Photo by John Karachewski.

Private funding also has played an important role. Since 1918, more than $135 million in contributions to Save the Redwoods has been used to purchase land that ended up in 39 state parks. That’s 154,000 acres, or 10 percent of the system. Those funds were donated with the understanding that the lands would be protected and accessible as parks in perpetuity.

So you can imagine how Save the Redwoods League executive director Ruskin Hartley felt when 16 of those 39 parks showed up on the closure list in May. He didn’t ask for his money back, but he did begin asking questions. “Cutting parks was not a budget necessity,” he said at a legislative hearing in Sacramento, “It was a choice the administration made.”

While acknowledging the seriousness of the state’s budget problems, Hartley noted that the $22 million cut was “barely enough to keep the state running for three hours, about the length of this hearing.” And if you divided those millions among the parks’ approximately 65 million visitors a year, you’d only need about 35 cents a visitor to fill the gap. Wasn’t there some way the state could have found that money?

- Starting young at Olompali State Historic Park. Photo by Galen Leeds.

Others raised questions about how the closure list had been assembled. In 2005 the parks department had declared Mono Lake Tufa Reserve and Castle Crags to be among the 29 units in the system with “the most outstanding natural resources values,” yet they were on the list. Jack London is a world-renowned historic park, yet it was there, too, along with 45 percent of the state’s 50 historic parks. Department staff considered nine criteria, including the parks’ natural and historic values. “But most of all, it was about net revenue,” state parks director Ruth Coleman says.

Early on, some park advocates doubted that the closures, which had been threatened twice before, would really happen. When the parks cut remained in the budget adopted in June 2011, however, nonprofits and local governments from the North Coast to the Salton Sea started scrambling for solutions to keep their local parks open. Some worked on raising funds to pay state staff salaries; others focused on helping with a subset of park operations such as visitor centers and campgrounds; others decided to try to run an entire park.

The latter is nothing new. Two state parks are already being run by nonprofits (El Presidio de Santa Barbara and Marconi Conference Center) and 32 by cities, counties, and special districts, including three in the Bay Area run by the East Bay Regional Park District. But the department said it would consider a host of new one- to five-year contracts, and the Legislature passed a new law, A.B. 42, to streamline the process by permitting the transfer of up to 20 state parks to nonprofits without legislative approval.

- Left to right: Gray Whale Cove State Beach, south of Pacifica; Castle Crags SP, south of Mount Shasta; wetland at China Camp SP near San Rafael. Photos by John Karachewski.

John Woodbury, general manager of Napa County’s parks department, was among the first to complete a proposal. In the heart of wine country, beloved Bothe-Napa Valley State Park was on the closure list, and he dreaded what that would mean for the community: “Everyone, from the sheriff to local park users, feared vandalism, homeless people moving in, and pot-growing operations.” Besides, if a park closed, it would have to meet the latest building codes and water system standards before it could reopen. That would mean “starting from scratch,” requiring a huge investment. “So we realized we needed to make a good-faith effort to keep it open,” Woodbury says.

This was not an easy proposition. Woodbury’s park district is small. His office has a minimal budget and one and a half paid staff. There was no way the county could subsidize the state park. “Right now the state spends $2 for every dollar it brings in at Bothe-Napa,” he says. “So you can see the magnitude of our challenge.”

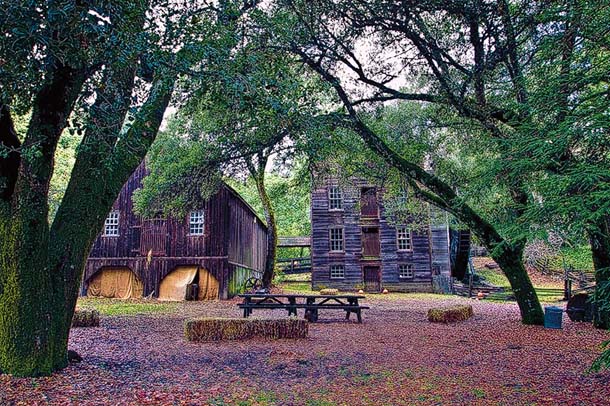

- Bale Grist Mill State Historic Park, south of Calistoga. Photo by Brenton Cooper.

But Woodbury believes that “with careful cost control,” a balanced budget can be achieved at Bothe-Napa–and at most other parks with popular campgrounds. To boost revenue at the campground, he plans to use a few old park buildings as vacation rentals and add 10 donated yurts. To shrink costs, he intends to hire a retired Bothe-Napa ranger at a lower pay rate than that of the peace officer/rangers who run most state parks. He would put maintenance and operations management under one person instead of two and increase the number of volunteer campground hosts. The county sheriff would be allowed to set up a substation in another park building in exchange for keeping an eye on the park. Theoretically, these measures would cut expenses and boost revenues by one third each, making the park self-supporting.

Here and elsewhere in the state, cutting expenses often means reducing the number, and sometimes the pay scale, of jobs. But the alternative–closure–would mean no jobs at all at a given park. As for the displaced workers, the department has said that those willing to transfer could likely expect to find a job elsewhere in the park system, due to many unfilled vacancies.

An hour’s drive from Napa to the west, the Sonoma County Regional Parks staff has made a bid to run Annadel State Park, a mountain biking, hiking, and equestrian mecca. In partnership with a grassroots nonprofit called LandPaths, the county hopes to go beyond simply keeping Annadel open. “We’d give people exemplary experiences in the park while being part of its stewardship,” LandPaths executive director Craig Anderson says. “We’d start by bringing out kids from every single school in Santa Rosa within walking distance. We’d see if senior communities could have picnics at the trailhead. We’d see if we could entice the 30-somethings with something kind of edgy and fresh.” Volunteers would help protect and maintain Annadel, too, making it more central to community life. Anderson’s vision, though born of the need for a short-term fix, reflects longer-term thinking about how to ensure a more robust future for public parks.

- A wildflower-covered hillside at Austin Creek State Recreation Area in western Sonoma. Photo by Kevin O’Connor, Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods.

If taking over parks was a stretch for counties like Napa and Sonoma, it would be a giant leap for most local nonprofits. While navigating the state bureaucracy, they instantly needed to learn about everything from waterworks to liability law. Meanwhile, the nonprofit California State Parks Foundation (CSPF), which had already helped beat back an earlier attempt at park closure through its Save our State (SOS) Parks campaign, launched a new campaign called “Defend What’s Yours,” aimed at mobilizing people’s affection for their favorite parks into effective advocacy. Deploying a series of smartly constructed blogs, social media postings, PSAs, videos, petitions, postcard salvos, and digital slide shows, the foundation encouraged its 130,000 members and the public to become involved.

CSPF also assembled a team of mostly pro bono consultants to help nonprofits negotiate agreements and expand their capacities to run parks. At the same time, the organization rallied business leaders under a “Closing Parks Is Bad for Business” banner. State parks are the main tourist attraction and economic driver in some rural counties. Yet those counties have fewer people and less money to deploy in efforts to avert a closure. CSPF pointed to a 2010 study showing that state parks generate more than $6 billion in economic activity annually, including $289 million in user fees and sales tax revenue. (See “The Cost of Closing Parks.”)

As of mid-March there was good news for nine parks on the closure list. At Antelope Valley Indian Museum, Henry Coe, McGrath, and Mono Lake, enough money was forthcoming from donations, grants, and (at Mono) new revenue sources to keep the parks open under state supervision. At Samuel P. Taylor, Tomales Bay, and Del Norte, the National Park Service, which has units next to all three, devised fixes; for Colusa-Sacramento River, the city of Colusa stepped up.

By February the parks department had scheduled workshops around the state “to help find park partners.” A request for proposals from concessionaires was being considered, too–not to run whole parks, but to take over facilities like campgrounds and snack bars. And the state was still in negotiations over operating agreements in more than 20 parks, with the clock ticking loudly toward dozens of park closures on July 1.

- Left to right: campsite at Salton Sea State Recreation Area in Imperial County, on the beach at Tomales Bay SP in West Marin (taken off closure list), Providence Mountains SRA in the Mojave Desert. Credits (L-R): © Chuck Graham, Kathleen Goodwin, Dan Suzio.

CSPF president Elizabeth Goldstein had mixed feelings about where things stood. “People are stepping up to find short-term ways to keep these places protected. That’s absolutely essential. But even if we get 70 operators operating 70 parks for three years, we’ll still be vulnerable. Parks will be ‘saved’ only when the state steps back up to take full responsibility.”

California state parks director Ruth Coleman is where the buck stops on the closure decision. It was not her idea to make the budget cuts, but she did pick the poison of closures. After 10 years on the job, she had her reasons. “For years you cut and spread the money,” she says, “and finally we got to this year and there was nothing left to cut and spread.”

Lately Coleman feels a little misunderstood. The parks department is not, she would like you to know, abandoning the 70 parks: “We’ll maintain our stewardship role, going in and looking over the cultural and natural resources. But we cannot operate them–at least not fully.” Nor is it selling the parks to the highest bidder. Though concessionaires may be allowed to run certain parts of a park, there are no corporate-owned state parks in our future.

People come up to her and say, “Have you thought of using volunteers?” She tells them about the annual 1 million hours of volunteer time donated and the $10 million netted by the department’s 84 nonprofit “cooperating” associations. “The public thinks it’s an easy thing to run a park,” Coleman says. “And then you start listing the things you’ve got to do. Wastewater treatment: You’re regulated by the water board, and they fine you if you don’t get it right. Drinking water supply: If you don’t get that right a lot of people will get sick. And we can’t indemnify private parties, so there are liability questions.”

By February, Coleman’s department–designed to run parks, not close them–was struggling. Only about half of the necessary savings were going to come from closures; it also had to make some $11 million in cuts at headquarters and through service reductions in the field. The “takeover” proposals were stacking up. Potential park partners complained that they couldn’t get clear information or timely decisions.

Coleman herself was having second thoughts about the costs of closing some parks. “Maybe we’re going to have to retain our staff in some places and cut elsewhere,” she admitted.

The very notion of “closure” was changing–beyond recognition for most ordinary park visitors. The department’s chief counsel believes that saying a park is closed will lessen the state’s liability. On the other hand, most parks have many access points; completely closing them would be impractical, if not impossible, and would likely encourage crime. Moreover, 17 parks on the closure list have received federal funding that requires they remain open. Others are subject to state law requiring public coastal access.

So Coleman has decided to redefine “closed” and keep the gates open. “To us, a closed park is really a no-service park,” Coleman explains. “Our operations there have ceased. But you can still walk there, and we would almost encourage you to go and take photos and blog. That will keep law-abiding people coming.”

In the long run, Coleman hopes to move her department toward a more “entrepreneurial” mindset. Fees at the gate and elsewhere provided about the same amount of money for parks as did the state’s general fund in 2009-2010. By developing a business plan for each park and holding staff accountable to revenue goals as well as high ideals, she aims to boost those earnings. “We’re not trying to turn them into businesses,” she says. “But we are going to be thinking about ways to generate more revenue and reduce costs. What can I do to market my park? Can I do partnerships with the Chamber of Commerce? Who’s not coming, and how do I get them there?” Coleman envisions new kinds of experiences that could serve the parks’ mission while broadening their appeal and boosting their income: perhaps an “aerial trail” (a zip line with elevated interpretive stations) near Monterey or a “canopy walk” showcasing the plants and animals that live near the top of a redwood forest.

“But we’re kidding ourselves if we think any of these places are going to be 100 percent self-supporting,” Coleman says. The failure of Proposition 21–a 2010 ballot initiative that would have boosted auto license fees to provide dedicated state park funding–along with the absence of any new proposals of equivalent scope, leaves the department with nothing but hard choices. “Californians inherited an extraordinary system that their grandparents were willing to pay for,” Coleman says sternly. “Today’s Californians need to ask themselves whether they are going to be bequeathing that to their children.”

That’s the inconclusive place where the story now stands, “at a hinge point in history,” says CSPF’s Goldstein. “No matter what happens now, state parks will be changed forever.” Park advocates’ efforts have been essential and in some cases heroic. They have bought time to search for solutions. But volunteers and local governments can’t run a system as massive and complex as California’s. That’s why the state has, up until now, funded a large, capable parks department with taxpayer dollars.

The parks department is straining under the weight of what’s about to happen. For the first time in the park system’s history, many parks will close on July 1, 2012–at least temporarily–and some may be irreparably damaged. Even those that stay open risk the death of a thousand cuts. And unless the state’s economy improves, even more cuts could be on the horizon.

Yet from this chaos has sprung creativity. According to Goldstein, “People are beginning to be mobilized in a way they haven’t been before.” In many locations, park staff have joined with local residents to fight to keep parks open. They are building momentum in the right direction: toward energized nonprofits, more flexible government, and generous private contributions of time and money. The parks idea of the early 20th century is being updated for the 21st century with broad, sometimes angry, but decidedly engaged public participation; people are joining with their neighbors; and they’re reconnecting with their parks.

The most interesting part of the story is yet to come. How will Californians respond from this point on–as park lovers, as taxpayers, as the entire generation in charge of California’s magnificent natural and cultural heritage? Whether we know it or not, we’re the park’s vital partners: Our parks don’t run themselves.

.jpg)