Rest your eyes on the tall trees and breathe the fragrant forest air—and a deep sigh of relief. You’ve escaped for a few hours—or all day—to ramble beneath a leafy canopy. Redwoods, Douglas-firs, tanoaks, and madrones shelter miles of trails waiting to guide you to creeks, ocean vistas, and a fantasy sandstone formation.

It could have worked out differently. Instead of 2,800 acres of open space, picture a hundred homes and an equestrian center along the road. And that cacophony in the background, echoing up the ravines? That’s the logging of second-growth redwoods—possibly mixed with the din of motorcycles.

Scratch that and breathe another sigh of relief! San Mateo County had already approved plans for such developments, but they were tossed aside forever when the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District acquired this land in 1985 and created El Corte de Madera Creek Open Space Preserve. After more than a century of use and abuse, the land began to heal.

The preserve takes its name from El Corte de Madera Creek, in the spring- and fog-fed headwaters of San Gregorio Creek. The name means “the wood-cutting place” in Spanish, a fitting moniker around here. While California’s North Coast boasts the tallest redwood trees and the biggest stands, it was here, in the Santa Cruz Mountains, at the southern end of the redwood range, that both the commercial logging of redwoods and the public outcry to preserve them began. El Corte de Madera Creek presents a view into this intersection of humans, history, and habitat.

- The rock’s surface is pocked with intricate formations called tafoni, produced byinteractions of winter rains and chemicals in the sandstone. Photo byJ.W. Wall, www.jwallphoto.net.

It also offers visitors abundant opportunities to wander among recovering redwood forests, now even more verdant after refreshing winter rains. Mosses and lichens plump up and unfurl on tanoak trunks. Hanging gardens, again lush with life, coat rocks, while tumbling creeks play background music. Orangish papery curls of madrone bark littering the ground relax and become supple. Drop your concerns about all those cars back on the road. With 36 miles of trails, this place absorbs people, and within minutes you can feel like you have it almost to yourself.

The preserve abuts Skyline Boulevard (Highway 35), which snakes along the Peninsula’s crest. The mountains slope relatively gently east toward San Francisco Bay, and commercial redwood logging began on those eastern slopes around the nearby town of Woodside during the 1830s. But these steep, rugged western slopes discouraged loggers until the 1860s, after the bayshore port of Redwood City had sprung up and the eastern side was mostly logged out. Eight sawmills operated in the preserve’s gullies and gulches, leaving an inescapable legacy, from old logging roads to “fairy rings” of second-growth redwoods encircling the stumps of ancients long since turned into lumber or shingles.

Yet in this densely forested landscape, a sandstone formation called tafoni steals the spotlight, especially for first-time visitors. Indeed, in 1974 the San Mateo County Parks and Recreation Department considered a 40-acre park around the “sandstone caves.”

The huge sandstone boulder in question perches on the north-facing slope of a steep ravine in the northern portion of the preserve, hidden among trees. As you approach, the trail’s long switchback frustrates then gratifies as it first guides you away from the boulder, and then back onto a viewing platform for a good look.

A sculpting process called cavernous weathering—or tafoni weathering, from tafone (plural tafoni), the Corsican word for “cave”—has scooped out hollows at the boulder’s base. But forgive yourself if your eyes don’t quite register these large “caves” so much as the intriguing honeycombed cells inside, called fretworks, stone lace, or stone lattice. Amid this vertical array of pockets and concavities, a few equally unlikely bulges, called cannonballs, protrude from the rock.

Limited by climate, rock type, and other circumstances, tafoni formations are uncommon. In this case, the stage was set some 30 million years ago when the Vaqueros Sandstone formed off Southern California’s shore. Deep sand sediments settled into a marine basin; then calcite, from the shells of marine animals, slowly cemented the sand bed together as it was carried north along the San Andreas Fault.

Cavernous weathering occurs in two phases, chemical and physical. The chemical phase requires distinct wet and dry seasons, which our Mediterranean climate provides. First, winter rains, slightly acidic from atmospheric carbon dioxide, soak into the rock. This mildly acidic water dissolves and begins to redistribute the calcite cement. Then, as summer’s warm, parched air slowly dries out the rock, the water, now laden with dissolved calcite, wicks outward. As water evaporates from the rock surface, the calcite it carried is left behind in the outer foot or so of the rock. Thus, summer drying concentrates the calcite cement, strengthening the outer rock and forming a hard outer crust, while weakening the inner rock.

Anything that breaks that crust—falling branches, hail, windblown debris, passing animals—begins the physical erosion of the rock and exposes the weakened interior to accelerated weathering. Breaching that crust leads to the large caves. Then the same processes working on the weakened inner rock form the fretworks. Sandstone isn’t uniform; better-cemented areas, called concretions, resist weathering, giving rise to decorations like the cannonballs. The stone lace develops because calcite-laden water takes the path of least resistance, along cracks. “Over time it cements those cracks, leaving the rest of the sandstone less cemented,” says naturalist and retired geologist Paul Heiple. “It’s a reverse topography.”

- Madrones, tanoaks, and other understory trees add color anddiversity of form to the forest. Tanoaks in the preserve have been thesubject of recent studies on sudden oak death. Photo by Misha Logvinov,www.verglasphoto.com

Nature needs thousands of years to sculpt these delicate decorations. Scrambling around the tafoni boulder endangers the formations as well as the scrambler, so resist the temptation. Besides, this is the only one of the district’s 25 preserves where venturing off trail can get you a citation.

When the district buys land, it not only inherits problems, it shoulders responsibility for remedies. “Our mission is not recreation first,” says the district’s Skyline Area Superintendent David Sanguinetti. “Protection of the resource takes precedence.” When the still-young district acquired this land, it allowed public access soon after purchase. Unfortunately, that created problems in this steep, disturbed terrain, when mountain bicyclists—then a relatively new user group—discovered old, erosion-prone roads and motorcycle trails. To address such inappropriate use, the district convened a citizens’ group that agreed upon the current trail system and the closure of all other old trails. Nowadays the district goes through a public planning process before opening new properties. “This is the preserve that taught us to do things differently,” Sanguinetti says.

More than just an eyesore and maintenance headache, trail erosion contributes sediment to creeks, which is of special concern in the San Gregorio Creek watershed, critical Central Coast habitat for steelhead trout and coho salmon. Steelhead is listed federally as threatened, and coho is listed both by the state and federal governments as endangered. Sediment ruins stream-beds for spawning by covering rocks and gravel and reducing pool depth. That means fewer places to lay eggs, fewer places for juveniles to hide from predators, and less food, too.

Research at the preserve is examining the effects of sediment and other habitat variables on another creature, the California giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus). Marbled in shades of red, brown, and copper, it’s one of North America’s largest salamanders—up to a foot long—and is found only in the Coast Range from Mendocino to Santa Cruz counties. Eggs laid in streambed gravel don’t hatch for several months, and juveniles remain in the stream for up to three years before metamorphosing into adults who move out onto not-so-dry land. Their ability to migrate is limited, so they depend on their home streams.

To protect downstream wildlife, the district developed a Watershed Protection Program in 2004 and revisited the state of the trail system. “It’s the first of its kind for the district, but it probably won’t be the last,” the district’s Meredith Manning says of the comprehensive plan.

A big part of the problem is that the old logging roads were poorly designed and never intended for year-round recreational use. Properly designed trails respect watercourses and natural contours and shed rain quickly, to prevent water from picking up speed, energy, and sediment. “We’re designing for big pulses of rain,” Manning says, and last year’s soggy March tested recent improvements. “They performed beautifully,” she says. Current work focuses on the mile-long Giant Salamander trail, closing it to all visitors until later this year.

Struggling fish populations and secretive salamanders aren’t the only concerns; a rare plant holds on here, too. The Kings Mountain manzanita (Arctostaphylos regismontana) doesn’t grow much beyond the Kings Mountain area along the ridge between Highways 92 and 84, and the California Native Plant Society considers it endangered.

- The preserve’s 36 miles of trails snake down steep canyonsthick with second-growth redwoods. The young trees give some sense oftheir giant forebears, which were logged out beginning 150 years ago.Photo by Misha Logvinov, www.verglasphoto.com

The woody shrub needs full sun, but doesn’t compete well in chaparral. “The strange thing about this manzanita is it’s an edge species,” says Cindy Roessler, resource management specialist for the district. “It loves to have its back up against the forest and its front to the sun.” The district maps its locations, avoids disturbing it, and also keeps an eye open for places to plant it. “But it’s hard to get it to germinate,” Roessler says. “We’re working with a nursery that is trying all kinds of different methods.” Propagators experimented with cold and hot temperatures, seed coat scratching, and simulated burning, but nothing has worked consistently.

Kings Mountain manzanita may be picky but it’s not shy. Its growth habit makes it easy to spot right next to trails. Look for it along Manzanita Trail, Fir Trail, and at the Vista Point, a lunch stop popular for its ocean view (fog permitting). It’s fairly easy to identify. You might first observe the strongly overlapping gray-green leaves. Upon closer examination, notice that leaf stems are short, or absent, so the leaves clasp the branch, which may be hairy. Deep lobes near the stem give leaves an elongated heart shape. In winter, they’re in bud and blooming, with clusters of pink lanterns opening as early as March.

Another plant to watch here, the tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus), is abundant for now. Three types of redwood forest dominate this preserve, and the company that plants keep can really matter. There are some small pockets of pure redwood, and a fair amount of redwood/Douglas-fir association, but a majority is redwood/tanoak association. So anything affecting tanoaks here could alter wide swaths of forest. Sudden oak death (SOD) has been hitting tanoaks hard up and down the coast, and it’s here too. But it’s not kicking in like it has elsewhere. “The unusual thing about El Corte de Madera Creek is that it doesn’t have very many California bays,” says Roessler. California bay laurel (Umbellularia californica) acts as a reservoir and spreader for the disease pathogen.

- El Corte de Madera is popular with mountain bike riders.Early problems with erosion led to a new management plan that became amodel for other Peninsula preserves. Photo by Aurora Meneghello, www.aurorameneghello.com.

The district has committed to help fight SOD, and El Corte de Madera Creek preserve is playing a role in two statewide research projects. Last fall 10,000 tanoak acorns were collected and catalogued from five locations around the state, including here, in a search for resistant strains of tanoak. Acorns will be planted under controlled conditions, and researchers will study any strains that resist infection. In the other effort, young tanoaks in already infested areas were injected with the pathogen, then months later cut down. The trunks were sliced thinly and examined microscopically to follow how the disease spreads through tree tissues.

As you wander the trails, the view in either direction along the abuse-to-recovery arc of this place is, well, foggy, as befits the redwood range. You don’t have to look hard to see signs of old roads being reclaimed by nature. You might wonder whether the rare manzanita and abundant tanoak will still grow here 200 years from now, and how big the redwoods will be. Then again, you can just take a grateful breath and be glad that this preserve is here, and so are you.

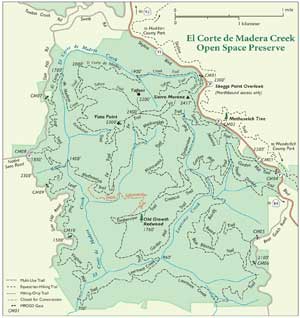

- Map by Ben Pease, www.peasepress.com

Getting There:

El Corte de Madera Creek Open Space Preserve has multiple entrances; the most accessible are along Skyline Boulevard (Highway 35). Skeggs Point, about 4 miles north of Highway 84 and 1.5 miles south of Kings Mountain Road, offers parking. (Note: Southbound traffic cannot turn left into the Skeggs lot.) During the wet season, some trails may be open only to hikers. Trail improvement and restoration work, continuing through 2009, may require temporary closures of some trails to all visitors. For the latest trail conditions, go to www.openspace.org or call (650)691-1200.

.jpg)

-300x221.jpg)