Q:Is there really a mole unique to Angel Island?

Yes, there is. And there’s also a mole unique to my lower left leg. Oh wait, that’s a different kind of mole. There are 39 species of mole in the family Talpidae, found mostly in temperate zones. Nearly all make a living in basically the same way: doing the breaststroke through dirt to find and eat earthworms. What an amazing notion—a life spent swimming through dirt in search of worms.

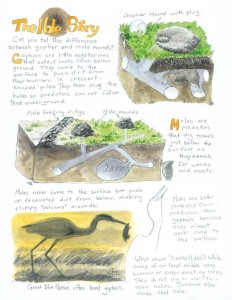

Moles “hunt” by creating temporary tunnels close to the surface that trap earthworms and other invertebrates, making it easier to detect and devour them as prey. They occasionally eat plant material but require a lot of animal protein, sometimes as much as half or more of their body weight per day. They dig more permanent tunnels deeper below the surface, which they use for traveling and breeding.

The broad-footed mole is extremely widespread and found everywhere in California except for the Central Valley and desert areas. Twelve subspecies exist, including the one on Angel Island (Scapanus latimanus insularis), which is considered a subspecies. Quick refresher: A species is an organism that is genetically isolated from other organisms. Generally speaking, members of a species can only produce viable offspring with others of their kind. A subspecies, by contrast, is measurably different from other populations of the same species. But, critically, these differences don’t prevent it from producing viable offspring with related groups within the species. So, like the ocean-swimming wolves of coastal British Columbia, a subspecies can emerge through hyper-adaptation to local conditions—or in the case of the Angel Island mole, via forced separation from its brethren.

How did these moles get to Angel Island? The breaststroke again? Well, for the last 2 million years or so, the earth has seesawed between ice ages and warmer interglacial periods. When the planet cooled, vast quantities of water were trapped in massive glaciers and ice fields. Sea levels worldwide decreased by as much as 400 feet. Just 15,000 years ago, Angel Island was a mountain rising from a lush valley with a river flowing past. But as the climate warmed, seawater flooded what’s now the San Francisco Bay, isolating the mountain and making Angel Island. Mating, and therefore gene flow, ceased between the small population of moles “trapped” on the island and the ones on the mainland.

In small populations there’s a tendency for any random genetic changes that arise to spread fairly rapidly. This genetic drift, as it’s called, can result in the quick emergence of differences of both appearance and bodily function compared to the original population. Drift probably explains why Angel Island moles look slightly different than moles on the Tiburon Peninsula, even though they’re closely related. And compared with its East Bay neighbors, the Angel Island subspecies is larger, has bigger feet and heavier front claws, and is slightly darker in color. The skull is also larger, more massive and with a broader nose.

But don’t be fooled. None of those differences mean much in terms of adaptation or speciation. If an island mole swam across Raccoon Strait and mated with a mole on the peninsula, the two animals would have healthy young. They differ slightly in appearance, but the two moles are members of the same species.

I could keep going on and on about this, but I really don’t want to make a mountain out of a molehill, if you get my (genetic) drift.