We walked from Richmond to Castro Valley and crossed only six streets.

It was quite a journey, and it started long before we hit the trail in Richmond. For me it began decades ago when I spent hours and hours running in the East Bay hills for my high school cross-country team. Once a week we met at the Skyline Gate Staging Area in Oakland’s Redwood Regional Park to run through the fog-dampened hills on the Skyline Trail. The journey also began when, as adults, friends and I ran the Nimitz Way in Tilden Regional Park, another stretch of the Skyline Trail. I wanted to connect these places that I had experienced separately, but knew were contiguous. Luckily, my friend Margie shared my curiosity and said yes when I asked her to join me on a hike that would stitch them, and more, together.

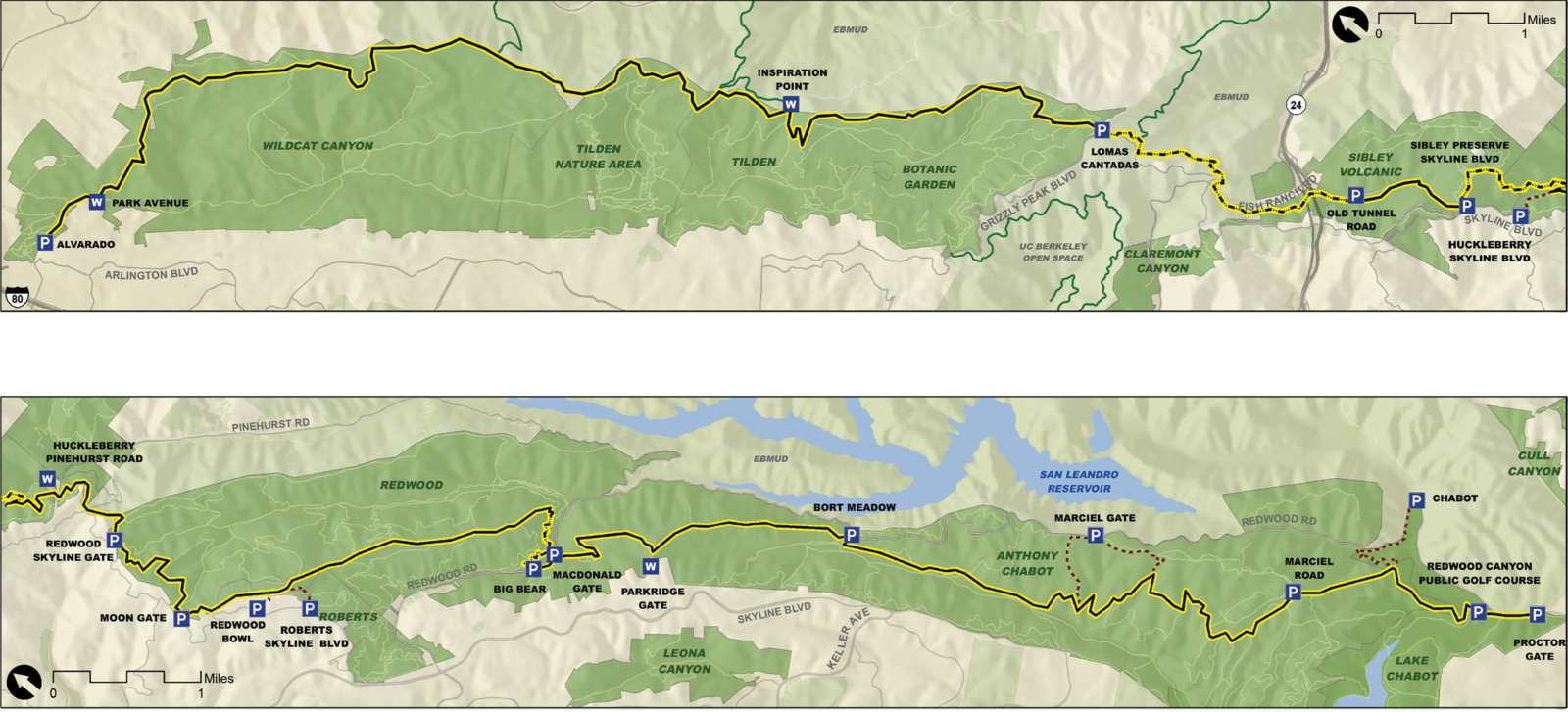

Over two days last August we traveled through six of the most beloved East Bay parks, loosely following the 32-mile East Bay Skyline National Recreation Trail (Skyline for short) and Bay Area Ridge Trail, on the ridgeline above open grasslands with an incredible view of San Francisco Bay to the west and Mount Diablo to the east, through maritime chaparral that supports rare plants, down into coast redwood groves, and to the shores of Lake Chabot. We connected to the contours of the trails, to the hundreds of people we saw in the parks, and to the layers of history that make up these parks and trails today.

Our walk started on a warm Saturday morning after we took a ride-share to the Alvarado Staging Area in Wildcat Canyon Regional Park. The northern end of the Skyline Trail is tucked up in a quiet neighborhood of Richmond surrounded by towering eucalyptus. We would hike to the Skyline Gate Staging Area in Redwood Regional Park, or about halfway to our goal, that day.

As we climbed up out of Wildcat Canyon, I considered all the people who must have walked here before us and was reminded of the book On Trails by Robert Moor, who after his through-hike on the Appalachian Trail examined the history of trails from every angle. Moor wrote, “Over time, more thoughts accrete, like footprints, and new layers of significance form…trails became cultural through-lines, connecting people and places and stories…”

Moor published those words in 2016, but it’s a sentiment that earlier helped create the East Bay Skyline National Recreation Trail, many of the East Bay Regional Park District trail networks, and trail systems nationwide. In 1968 President Lyndon Johnson signed the National Trails System Act, which called for creating trails that provide “a variety of outdoor recreation uses in or reasonably accessible to urban areas.”

EBRPD leaders like Richard Trudeau and Hulet Hornbeck saw the national attention on trails as a way to build and maintain a world-class trail system here in the East Bay. “The district was the first local agency to designate a trail under the National Trails System Act,” says Robert Doyle, general manager for EBRPD. “The act was the recognition that Hornbeck and Trudeau needed to promote the regional trail system we have today throughout the district.”

The idea was that if you connected the parks scattered through Alameda and Contra Costa counties by trails, their sum would amount to something greater than the parts. The “parks, instead of being isolated land entities someplace, are now tied together with trails…and [it] becomes in reality a system that belongs to every resident of the district,” said George H. Cardinet Jr. in a 1982 interview about his time with the East Bay Area Trails Council. The Skyline Trail became one of the nation’s first recreation trails and is one of 1,307 today.

As we walked that Saturday, we noted the placards with the national trail icon—or in trails parlance, ‘disks’—on signs along the Skyline Trail, and we laid down another layer of footsteps and another story.

We hiked out of Wildcat Canyon to the ridgeline, listened for the dull roar of Highway 80 to the north and west, and caught sight of busy chickadees to the east and south. The dry rolling hills of late summer spread out around us. Soon we entered Tilden Regional Park and were struck by all that was happening in this one park. We walked by dozens of cows grazing on the hillside, a golf course, about 15 kid birthday parties, and some doting grandparents taking their grandchildren to the steam train for a ride through the redwoods. Our urban parks serve so many purposes, from long hikes to family gatherings to forging bonds with others who love these places too.

It’s that love we give to our trails that keeps them alive. Today the 800-strong staff of the 85-year-old EBRPD care for over 1,200 miles of trails throughout, and connecting, more than 122,000 acres of parkland. And they couldn’t do it without volunteers. Within the EBRPD 11,241 volunteers have put in more than 52,250 hours since 1996 through the district’s Ivan Dickson Volunteer Trail Maintenance Program. Citizens at the local nonprofit Oakland Trails, which helps tend City of Oakland trails and parks, have spent thousands of volunteer hours contributing to general trail upkeep, but also welcoming users and providing directions to the occasional lost hiker. Without the contributions of regular people like you and me, the trails of the East Bay would not be what they are today…and there’s no way Margie and I could have hiked so far through such a populated area and encountered just six roads.

While still in Tilden, we crossed Wildcat Canyon Road (Road #1) and Lomas Cantadas (Road #2) near the steam train. After leaving Tilden, we entered Hidden Valley Preserve, which is EBMUD land (permit required!), and crossed Fish Ranch Road (Road #3), then Old Tunnel Road (Road #4) into Sibley Regional Volcanic Preserve.

A favorite part of the trip came at the northern end of Sibley. Margie and I stopped walking because what our eyes were seeing did not match what our ears were hearing. We stood in a mixed forest of bay laurels and coast live oak. Several wood rat nests were nearby. Their nests resemble huge piles of sticks with some order to them, but mostly look like a larger version of the children’s game pick-up-sticks. The sounds here in the forest should be peaceful. But instead, all we could hear was the loud roar of a freeway.

We were standing a few hundred yards above the eastern entrance to the Caldecott Tunnel. Through small gaps in the canopy, we could make out the cars on Highway 24 about to enter the tunnel. I wonder if the drivers and passengers zooming through it ever think about standing on top of it? Are the wood rats aware of how many millions of humans are living around them? It was a brief reminder that we were hiking an urban trail, where forest and metropolis meet.

The Skyline Trail also follows parts of the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail and a section of the Bay Area Ridge Trail, the latter conceived 30 years ago to create a 550-mile-long trail following the ridgelines and ringing the Bay Area. Today there are 375 miles and counting of Ridge Trail open to the public. Someday Margie and I hope to circumnavigate the Bay while staying in hut-to-hut facilities and campgrounds, a vision the Bay Area Ridge Trail Council has for everyone, according to executive director Janet McBride, and partners like EBRPD. The beginnings of this concept are visible at Sibley, where there’s a hike-in campground with 180-degree views of Mount Diablo, Vollmer Peak, and Tilden Park.

Heading south from Sibley, we entered and wound our way around Huckleberry Botanic Regional Preserve. We went downhill and then back uphill, surrounded by a remarkable diversity of plants. Several groups were walking the trails, stopping along the way to consult the signs identifying the unusual flora that grows here. We kept our focus and continued south until we exited Huckleberry. It was there that we crossed Pinehurst Road (Road #5).

Redwood Regional Park begins on the southern side of Pinehurst Road and from there we walked another mile to the Skyline Gate Staging Area. Then we called it a day. We had walked 15.7 miles and climbed a total of 3,470 feet. It was time to put our feet up and ponder what we had just accomplished.

The next Saturday, we started where we had left off and quickly dropped down onto the Stream Trail, which runs parallel to the Skyline Trail and descends into the redwoods. Unlike on the previous Saturday, it was the silence that overwhelmed us on this day. There is a bowl-like area in Redwood Regional at the Stream and Mill trail junction where you can’t hear anything but your own breath. It feels absolutely silent. The fact that eight million people live around you is inconceivable here. Those towering redwood trees absorb more than carbon; they absorb sounds and the stress of city life.

In the quiet, I again began thinking about who had walked these paths before national trails were a thing, before the EBRPD existed. This was where the Chochenyo Ohlone lived and thrived for thousands of years before the Spanish arrived, and it is still their homeland today. Their stories, told in their language, and their footprints are part of this place, too.

In the southern section of Redwood Regional, Margie and I stopped chatting. The trail had ascended out of the redwoods and into the manzanitas. The sun shone down onto the shoulder of the trail covered in bay laurel leaf litter. Margie was in front of me at that point, and she suddenly stopped in her tracks. It sounds like Pop Rocks, she said, those bizarrely good candies that crackle in your mouth. We realized that the leaves were crackling in the sun. Why? How exactly? We didn’t know. But we stopped to listen for a while and to be amazed.

The second part of this ambitious walk encompassed three parks: Redwood Regional Park, Anthony Chabot Regional Park, and Lake Chabot Regional Park. Leaving Redwood Regional on the southern end of the park meant crossing Redwood Road (Road #6).

Margie and I were giddy when we reached the northern edge of Lake Chabot. Seeing a large body of water—even though we weren’t walking across a desert—felt like a relief. It’s not a small reservoir, so we had more walking to do. But we had made it. We had spent hours in the peaceful valleys and the scenic ridges of the East Bay hills. And we made it.

Walking the paved path around Lake Chabot, we were two white women in what looked like a gathering of the United Nations. A Korean grandmother held the hand of her Pokemon Go–playing grandson. A group of twentysomething Indian women talked and laughed. A Latino family played Frisbee on a lawn. Women wearing hijabs waited for their friends outside the cafe. A large group of Taiwanese people had reserved a picnic area and someone was singing a traditional song using a portable microphone. And on and on. There were hundreds of people outside. Returning stray Frisbees to each other, sharing a lighter to start the barbecue. We couldn’t help but feel how alive this park was with people and energy.

“The core function of any trail is to connect,” wrote Moor in On Trails. “The root of that word, from the Latin connectere, means to ‘bind together’ or to ‘unite.’ In this sense, a trail strings a line between a walker and her destination, uniting the two in an uninterrupted corridor so that the walker can reach her end swiftly and smoothly.”

There are many beginnings to this story—the Chochenyo Ohlone people, the National Trails System Act, Hulet Hornbeck’s vision, high school cross-country practice, our first steps at Wildcat Canyon that day in August—and there are just as many endings. The story keeps going every time we visit a park or walk a trail. Last fall, Margie’s two sons ran on the cross-country team for their high school and built some kind of relationship to the hills they climbed. Perhaps my two sons will run those trails when they get to high school, too.

Passionate citizens mobilized to create the National Trails System Act in the first half of the 20th century, which resulted in recreation trails across this country, uniting places and people. Walking the East Bay Skyline National Trail left me wondering what we as citizens can do when we work together for the public good. It inspired to me to want to walk more long-distance trails, and to roll my sleeves up to ensure that future generations can, too.

As President Johnson said in 1965: “There is much the federal government can do, through a range of specific programs, and as a force for public education. But a beautiful America will require the effort of government at every level, of business, and of private groups. Above all it will require the concern and action of individual citizens, alert to danger, determined to improve the quality of their surroundings, resisting blight, demanding and building beauty for themselves and their children.”

Walking from Richmond to Castro Valley was exhausting. The energy I had in high school has decreased just a bit. But mostly I remember the walk for the feelings it brought: connection to the past and the future, to myself and to others. And it is from that connection where hope grows and thrives.