On a ridge atop Las Trampas Regional Wilderness near Danville, a naturalist and I come across a large track in the mud. It’s rounder than a dog or coyote track, with three scallops along the back of the heel pad. We silently stare at it from all angles and snap some pictures. After a long pause, the naturalist, Jim Hale, smiles: “It’s probably a puma.”

Top predators generally don’t do well in suburbia. But whether you call them pumas, panthers, wild cats, cougars, catamounts, or mountain lions (all Puma concolor), these big cats have somehow endured in the Bay Area. Few people see them. A 1990 initiative made California the only state to ban trophy hunting of pumas and also devoted $30 million a year to habitat protection. Nevertheless, the state Department of Fish and Game estimates that only 4,000 to 6,000 pumas are left in all of California, and it can’t give you a local head count or even tell you whether the population is stable, growing, or shrinking.

Yet marks in the mud like the ones we’ve just seen–and other evidence–suggest that one of North America’s most powerful predators is quietly going about its business in a Bay Area shaped by and shared with more than 7 million people. At first, the idea of a puma in a metropolis seems nothing short of miraculous. How could such wildness persist alongside so many people? In research that took me from a remote ridgetop to a forested freeway overpass to a popular shopping center, I learned about what cats need and where they get it amid the lands of the East Bay Regional Park District and adjacent open spaces–and what the entire Bay Area might learn about living with wildness as our human population continues to grow.

Despite the East Bay’s intersection of big cats, big open spaces, and millions of people, there’s never been a major study of pumas in Alameda and Contra Costa counties, says East Bay Regional Park District wildlife ecologist Steven Bobzien. That may change in the next few years, as a collaborative effort called the Bay Area Puma Project looks to expand from the Santa Cruz Mountains into the East Bay and Marin. “There’s been a lot of discussion over the past decade and a lot of interest in doing a study, but there hasn’t been funding,” says Bobzien, who has been involved in puma research since 1995. The hope is to bring together academic researchers with agencies like park and water districts that own the bulk of protected land in the Bay Area, to start amassing hard data on how pumas are faring in our region. “We’re just right now on the front end of that,” he says. Meanwhile, much of what we can say about pumas in the East Bay is based on the anecdotes and experiences of folks who spend a lot of time out in the parks.

- Deer, like this one at Coyote Hills Regional Park in Fremont, are the big cats’ main prey, so wherever deer thrive, there’s a chance lions will too. Photo by Jerry Ting.

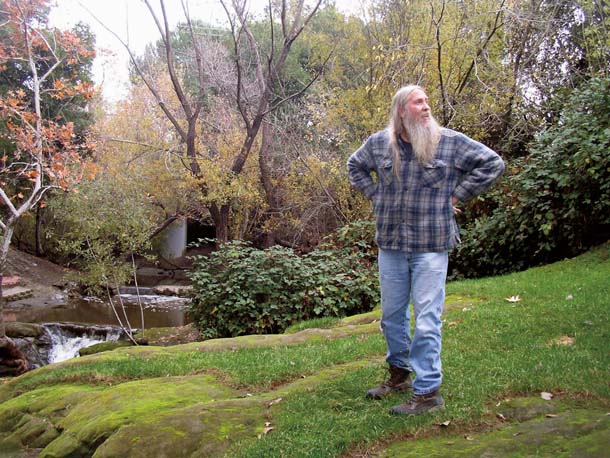

Exploring the puma’s peregrinations in suburbia is one of the wide-ranging interests of Jim “Doc” Hale, a biological consultant, outdoor educator, and member of Contra Costa County’s fish and wildlife advisory committee. The 60-year-old Hale has lived in Contra Costa County all his life, and he’s seen plenty of pumas in the Bay Area, by tracking or spotlighting them, by photographing them with hidden cameras, and sometimes simply by paying attention while taking a drive or a walk. On our first outing, Hale drives up in a white Jeep with “zoology” spelled out on the license plate. With his gray ponytail, foot-long beard, and well-worn clothing, he seems to belong in an earlier century or a wilder place.

We set out late in the afternoon, because pumas are more likely to be active then than during the day. You might think they would be easy to spot, given that most adults weigh 80 to 150 pounds. But finding them is harder than bird-watching on a bad day. If you’re lucky enough to get a glimpse, by the time you’ve raised your binoculars, your quarry is gone. Contra Costa County game warden Nicole Kozicki receives some 20 calls a month from people who think they’ve seen one, but upon investigation most of those sightings turn out to be bobcats, golden retrievers, or even house cats. Hale says the cat’s two- to four-foot-long tail is the key identifier. He always asks about it when talking with people who think they’ve seen a puma. If they didn’t see a tail, or if they say it was short, it probably wasn’t a puma.

In our first two hours of roaming, we see an alligator lizard, a great blue heron, and some wild turkeys. We bow to examine the tracks of deer, coyotes, horses, domestic dogs, and wild pigs, as well as the linear excavations of a broad-footed mole. We hear the screech of a red-tailed hawk and the chirps of sparrows, wrens, juncos, and nuthatches. When it gets completely dark (“my favorite time to be out,” Hale says), we hear a coyote chorus and the deep crooning of a great horned owl. But no sign of any pumas.

That’s hardly surprising. “I’d love to see one,” says game warden Kozicki. But in 21 years at a job that frequently takes her into puma territory, Kozicki has never been so lucky. Pumas are experts at making themselves invisible.

- A view north from Eagle Peak in Las Trampas Regional Wilderness, at the heart of one of four areas in the East Bay where there is enough connected open space to support mountain lions. Photo by Miguel Vieira.

In classic stealth fashion, in 2005 a puma showed up at Coyote Hills Regional Park, right on the Bay, just west of Fremont’s maze of light industry along Interstate 880. To get there, says Bobzien, the puma likely walked from somewhere in the open space lands around Sunol Regional Wilderness down the Alameda Creek flood-control channel past farms, fields, and Fremont–a city of more than 200,000 people. But Bobzien knows of no reports of anyone seeing it along the way.

Pumas’ invisibility may well be one of the reasons they are here and other top predators, such as grizzlies, are not. But a good disappearing act is not enough. Pumas also need food, water, and lots of open space. On my second trip with Hale, I get a dramatic, cat’s-eye view of some of the best habitat the Bay Area has to offer.

- This puma was photographed by an automated camera one night along the headwaters of San Antonio Creek, near Ohlone Regional Wilderness. Remote cameras are a good way for researchers to record the presence of these elusive cats, who are skilled at remaining undetected. Photo by Joseph DiDonato.

Hale takes me to Las Trampas Regional Wilderness. As we walk up a fire road to Rocky Ridge, he points out the spot where he and some friends got an unusually long, daytime look at a large reddish puma tomcat on a slope 50 yards below. “He was sitting there in the morning sun, flagging his tail and rolling around in the grass. He saw us, too, but wasn’t bothered. He sat up on his haunches and licked himself.”

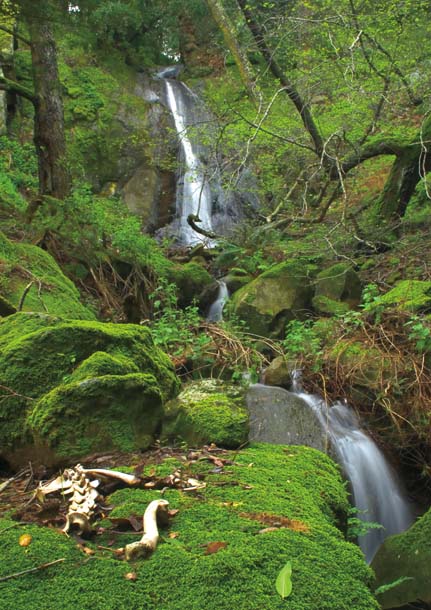

- At a likely kill site in a remote section of Las Trampas Regional Wilderness, bleached bones of a blacktail deer sit next to a 30-foot waterfall far from the park’s well-traveled trails. Photo by Kevin Fox, kevinfoxphotography.com.

On the hillside where we’re standing, small creeks lined by mossy oaks and bay laurels curve down through open meadows. The tracks of deer, the puma’s primary prey, pock the mud like wet parentheses. “You can see why this is prime puma habitat,” Hale says. “You’ve got the three basics: food, water, and cover. There are deer all over the place here.”

Pumas don’t have the lung power for long chases (which is why hunting dogs can drive them up trees). Instead, pumas ambush–lurking in rocks or shrubbery until they spy a passing meal. “They’re super fast in a short burst,” Hale says. “There are records of them jumping 45 feet horizontally and 15 feet straight up from a standstill. Sometimes they’ll jump from a tree.”

According to the California Department of Fish and Game, pumas have attacked humans in the state 16 times since 1890. Only six of those attacks were lethal. There hasn’t been a fatal attack in the Bay Area since 1909, when a woman and her son died of rabies after being bitten by a rabid puma in Santa Clara County. “These cats are doing a really good job of avoiding people,” says Bobzien, who gets about 20 credible reports of sightings each year. “People shouldn’t be frightened. If they’re concerned, they should just take some precautions: Walk with a dog or hike with a friend.”

Hale and I have just climbed up to 2,000 feet on Rocky Ridge when we spot that puma paw print in the mud. Then we take a long look at the view. To the east, Las Trampas Ridge eclipses the suburban towns of Alamo, Danville, and San Ramon, and we see almost nothing but open space in all directions–a happy reminder that only about 16 percent of the Bay Area’s 4.5 million acres lies beneath pavement and buildings. Some 20 percent is protected by agencies like the regional park district, the San Francisco Water Department, and the East Bay Municipal Utility District, and the rest is privately owned wildlands, farms, and ranches and the waters of San Francisco Bay. “The Bay Area has the best regional park system in the entire country,” Hale says, beaming.

- This treed female was about to become the 13th puma fitted with a tracking collar by researchers from the Bay Area Puma Project, a program of the Marin-based Felidae Conservation Fund. Photo by Trish Carney for the Felidae Conservation Fund.

If all pumas needed were open space, the species’ future would be secure in the Bay Area. After all, a UC Berkeley study around Mount Hamilton in the 1980s found that a hundred square miles of good Bay Area habitat can support five to eight pumas, though that number can vary a lot based on habitat quality and prey availability. The East Bay alone has four areas of almost this size or greater: one centered around Las Trampas, Chabot, Redwood, Huckleberry, and Sibley regional parks; another at Wildcat Canyon, Tilden, and Briones regional parks; a third at Mount Diablo State Park, Black Diamond Mines, and Morgan Territory; and the fourth spanning regional parks and wildernesses at Sunol, Ohlone, Del Valle, and Mission Peak. Providing even larger expanses of good puma habitat are the open spaces of Marin, Sonoma, Solano, and Napa counties to the north and San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz counties to the south.

- Felidae Fund Executive Director Zara McDonald and Puma Project Field Ecologist Paul Houghtaling examine the 93-pound lion, captured in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Photo by Trish Carney for the Felidae Conservation Fund.

In the long term, though, pumas need more than large chunks of open space. To find food and avoid inbreeding (which can eventually imperil the population), they need to be able to move freely from one chunk to another. Yet getting from, say, Las Trampas to any of the other puma habitats mentioned above requires crossing at least one major freeway. So Hale and I went off to sample the quality of some of those crossings.

For animals in the Oakland-Berkeley hills, the best route across Highway 24, which runs east-west from Oakland to Walnut Creek, lies above the eastern end of the Caldecott Tunnel. You can walk along it on the Skyline Trail, though few people do. And that’s fine with the pumas, which must see this narrow band of forest as an Eden where humans and their roaring machines briefly disappear. Pumas and other wide-ranging species that find this sliver of habitat can safely move from one “island” of open space to another.

Pumas are successfully crossing highways in much less congenial places too. In Lafayette, for instance, tracks indicate that pumas coming down from Lafayette Reservoir have been using the shoulder of El Nido Ranch Road to trot under the freeway and head north through a mile-wide residential area to Lafayette Ridge and Briones Regional Park. It’s a dodgy route that requires “a little bit of backyard cruising,” Hale says. But the pumas are traveling when most human residents are indoors, asleep.

“In these affluent areas, most of the houses are on good chunks of land,” says Hale. “There’s not a lot of fencing and the creek corridors are still there.” Once a puma makes it to Lafayette Ridge, it can travel in relative safety to the inner reaches of Briones, as well as to Tilden and Wildcat Canyon regional parks; adjacent EBMUD lands in the watersheds of Pinole Creek and San Pablo and Briones reservoirs; and private agricultural lands (where they occasionally disturb livestock, but favor deer and other wild prey).

- Jim “Doc” Hale, a local biological consultant, says he’s recorded puma tracks in this stretch of creek habitat right in Walnut Creek. Photo by Joan Hamilton.

But many cats don’t survive highway crossings, and road kills are among the highest causes of mortality for pumas, says Bobzien. Cats of all ages get hit, but the pumas most likely to risk highway crossings are juveniles–one- or two-year-old males leaving their mothers to try to establish new territory. Also on the prowl are a few older males, pushed out of their former haunts by larger, stronger competition. This is not to say that pumas in their prime don’t occasionally venture into inhabited areas. They do follow deer into lushly (and to the deer, deliciously) landscaped backyards on the edge of open space. “People who move to the edge of parks sometimes report that pumas are in their backyards, “Hale says. “But they moved into the lions’ front yard.”

After we’ve checked out the Caldecott Corridor and the underpass in Lafayette, Hale suggests we go puma watching in, of all places, Broadway Plaza in downtown Walnut Creek. A hyperactive hub of human activity, Broadway Plaza has Macy’s, Nordstrom, and myriad other businesses, along with heavy traffic and sprawling, car-crammed parking lots. A few blocks east of where Highway 24 and Interstate 680 come together, “it’s the center of the known universe,” Hale jokingly says, or at least the place where most of the people in eastern Contra Costa County do their shopping.

As we drive through the crowded streets, I’m wishing I were back on Rocky Ridge. But Hale is undaunted. He parks the Jeep next to a high-rise office building overlooking a small, tree-lined ribbon of water. It’s San Ramon Creek, looking at first like a token swath of greenery. But Hale calls it “one of the county’s best sections of riparian habitat, right here in the city. It serves as the only natural environment in a suburban/urban interface. Therefore it’s extremely important for wildlife movements in the county. We’ve got oaks, buckeyes, alders, cottonwoods, and all the classic riparian species. We still have chinook salmon and rainbow trout, mink, beaver, turtles, and river otter. I’ve also documented coyote, bobcat, gray fox, mountain lion, and red fox–all using this creek.”

- Photo by Jeffrey Rich, jeffrichphoto.com.

The thought of pumas and Macy’s almost side by side suggests that it doesn’t take much to enable these top-of-the-food-chain predators to pass discreetly from one open space area to another. But will they survive as human pressures increase? Experts aren’t sure. Bay Area citizens have voted, time after time, to support the extensive system of open space areas that supplies the basic food, water, and cover that pumas need. From the perspective of such wide-ranging wildlife, however, our investment in those areas is not yet secure. Public education is vital to help people shed irrational fears of pumas and convince them to support keeping creeks and other key habitat open. Easements and land purchases may also be necessary. “To protect a species like the puma,” Hale says, “we have to acquire the last remaining links–the lands that will serve as corridors to link all these open spaces together.”

Determining exactly where the region’s most vital links are is the next step. Working with Chris Wilmers of UC Santa Cruz and the California Department of Fish and Game, the Felidae Conservation Fund’s Bay Area Puma Project has been radio collaring and following pumas in the Santa Cruz Mountains for the past two years. With support from organizations like the East Bay Regional Park District, the Puma Project hopes to extend its studies to the East Bay by 2011. “We want to look at the entire Bay Area population,” says project founder Zara McDonald, “and identify and rank the key habitat and corridors for these cats.”

In the meantime, Bay Area residents can walk in the hills knowing that a puma might be watching them. Like me, they probably won’t get to see a cat in the flesh, even with diligent effort. But they might see a track. And that track will be more than a mark in the mud. It will be a sign that we live in a community big enough, in size and in spirit, for both the cacophonous world of people and the silent world of the cat.

.jpg)

-300x221.jpg)