There are two things that make the San Pablo Bay shoreline different for wetland planners than any other shore in the region: more space and fewer neighbors. Baylands here butt up against pastures, hills, and river floodplains, rather than against hard walls. It’s more rural. Designers see space for wetlands to spread out and creep inland in advance of rising seas. With so few neighbors, the land trusts and government agencies that manage the landscape usually only have to invite county officials and a few ranchers, vintners, and hunters to any stakeholder meeting. This is a whole different context than the South Bay, with its myriad neighboring cities, dog-walkers, ports, cyclists, park districts, flood management agencies, sanitary districts, and corporate office parks.

Getting Close to Primeval

Noodling around in the sloughs with two engineers from Ducks Unlimited in a Boston Whaler on a warm spring morning, we see one fisherman, two northern harriers, a dozen lesser scaups, hundreds of peeps, and thousands of acres of very shallow water and wet mud. The tide is going out, so we have to move quickly. But there is much to see here at the southern end of the Napa River, particularly the seven former salt production ponds, some more than 1,000 acres in size, now open to the tides. At one point, it gets so shallow that Russ Lowgren, the ex-navy engineer in a camo cap at the helm, has to put on waders, climb out of the boat, and push. On one side of the whaler the water is waist high, on the other knee-deep, but Lowgren isn’t surprised. That’s what happens when you open up thousands of acres of diked marshes to tidal flow and connect them to a river–some areas scour out while others begin silting in.

Such shifts in the mud may be invisible in a foot of water but are commonplace in any active estuary. Where the South Bay is often called a lagoon-like backwater, the North Bay is on the receiving end of every storm and flood of fresh water flowing down the Petaluma River, the Napa River, and the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, as well as emptying out Tolay, Sonoma, and Huichica Creeks. “It’s a giant natural estuary,” says Don Brubaker, manager of the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge, who’s along for the ride. Standing on the prow of the whaler, Brubaker sweeps his arm around 360 degrees to emphasize the extent of the historic estuary he is talking about. “Restoration here will have long-term benefits for estuarine productivity–we may lose hayfields and salt ponds but we’ll gain fish and crustaceans.”

At this moment, we’re in China Slough, one of the few named sloughs in the state-owned Napa-Sonoma Marshes Wildlife Area. Lowgren and fellow Ducks Unlimited engineer Steve Carroll are showing off their work on various ponds. As part of their construction contract with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Ducks Unlimited scraped the first two feet off some levees to allow overtopping at high tide, strengthened others to protect roads and neighbors, and graded others to give wildlife more transitional habitat. They also strategically placed breaches to maximize either sediment build-up or scour, and retooled numerous siphons, gates, and other water control structures left behind from the salt production days. They even built island homes for endangered California least terns on one of the ponds.

The biggest bugaboo in restoring this landscape block of old salt ponds was the actual site of the original salt production plant, which included crystallizing beds and pickling ponds right on the edge of the Napa River. Restoration managers couldn’t just breach and run, because the salt levels released into the river would have killed fish.

As it turned out, the first step involved reopening the fallowed plant. Cargill pitched in, harvesting 350,000 tons of salt within three years. But the crystallizer beds still had salt concentrations up to 360 parts per thousand (ppt) that had to be reduced through dilution to river background levels of 20 to 30 ppt before discharge.

A team from URS Corporation, led by habitat engineer Francesca Demgen, experimented with dilution and discharge methods in the lab; then Cargill took the experiment to the next level by engineering a three-acre field test, which earned the project its discharge permit.

Based on what they’d learned, URS and Ducks Unlimited conducted the first breaches of the crystallizer beds in several stages, so the salt could dissolve and flow out out of the ponds into the river gradually over a period of two weeks. They also designed the breach sites carefully. “Instead of cutting the breach down to low tide levels, we cut it only partway down,” says Demgen. “Since salt is heavier than water, only a little went out into the river at a time.”

The return of the site–now the Green Island Unit of the Napa-Sonoma Marshes Wildlife Area–to full tidal action was finally completed in 2010, finished up with the help of federal stimulus dollars. “Salmonids entered it at lightning speed,” recalls Demgen.

For someone coming in for the first time, floating along these sloughs with the new marsh forming all around is as satisfying as chocolate. In the distance, mountains–Tam, Cougar, Veeder, Diablo–seem to frame the endeavor with California’s golden glow, all marking the edge of lowlands and valleys flooded by the rising seas 10,000 years ago. It’s a nurturing environment, low and quiet, warm and natural in the sunlight. It may be about as close to primeval, out there in the growing San Pablo Bay marshes, as it gets in the Bay Area.

“Everything has come out exactly as expected,” says Carroll, half jokingly but also with the confidence of a guy who has tried out a lot of different things on large and small landscapes and knows the best and worst of what can happen from experience. No wonder rolling up his jeans to help Lowgren push the boat didn’t faze him one bit.

History in the Making

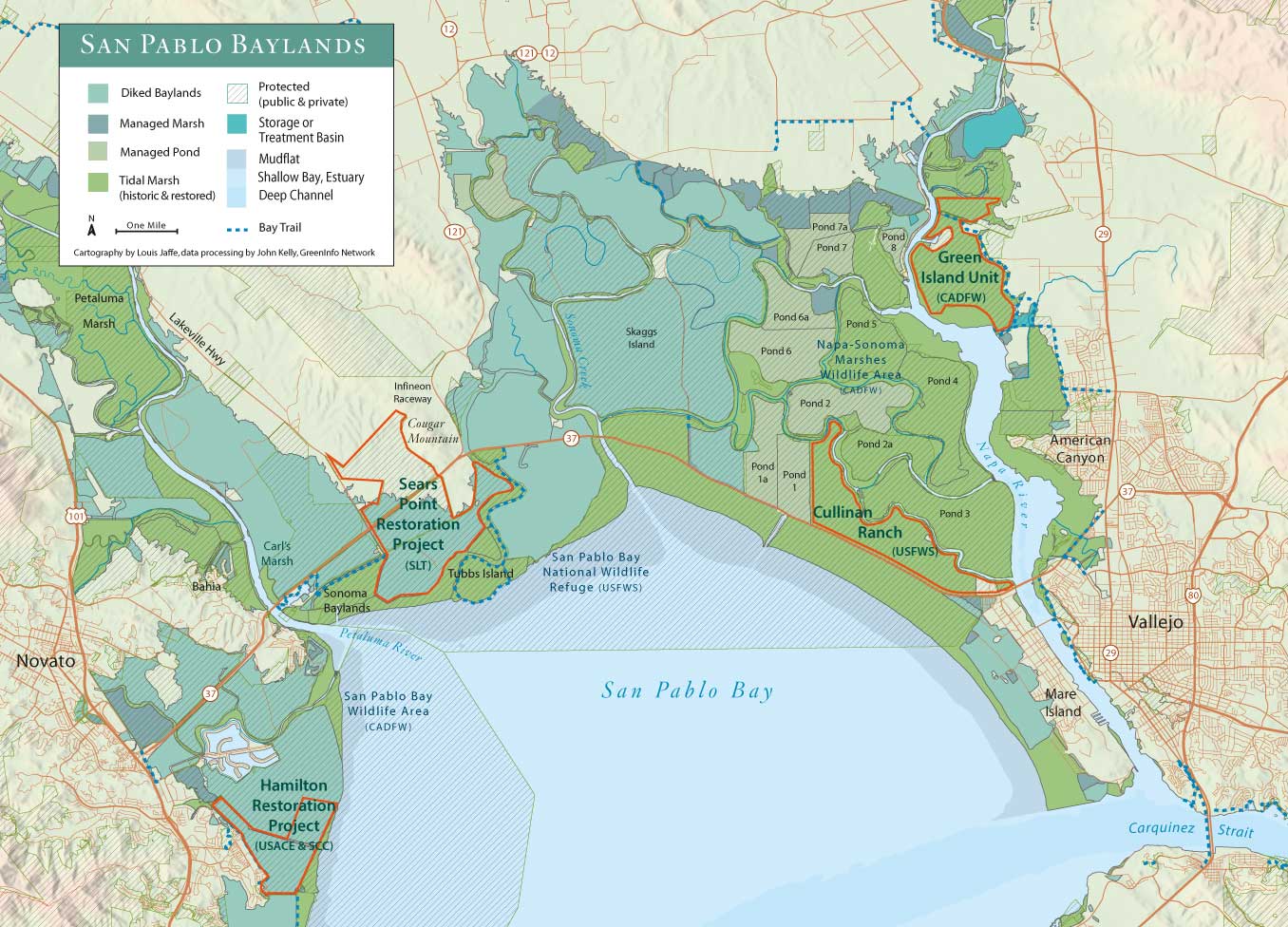

If you drive along Highway 37 from Novato to Vallejo, you can almost see the entire 30-year history of wetland restoration in 20 minutes. Each property has its own story, but the benchmark may well be the Petaluma Marsh just north of the first bridge. Here the Petaluma River is bordered by lushly vegetated wetlands, never diked or disturbed. Talk to wetland designers about these and an awestruck look comes into their eyes. Every comparison they make, as they struggle to re-create wetlands thousands of years old in mere decades, is to a marsh like this.

Also visible is Carl’s Marsh, named after one of the first people with a bigger vision for the Bay’s wetlands, state biologist Carl Wilcox. In 1994, Wilcox knocked two 50-foot holes in the Petaluma River dike, creating a marsh out of a run-down farm field practically overnight. There was enough sediment circulating in this corner of the Bay that the marsh gained six feet in vertical elevation within four years. According to Point Blue Conservation Science (formerly PRBO) biologist Julian Wood, Carl’s Marsh now hosts five pairs of clapper rails and 60 pairs of song sparrows. “To be able to create habitat for endangered species out of nothing, that quickly, is amazing,” says Wood. No wonder Carl’s Marsh is a rock star on the restoration stage.

For nearby Sonoma Baylands, a 300-acre site owned by the Coastal Conservancy, things didn’t go quite so smoothly. It was here in the 1990s that planners conducted one of the first large-scale experiments in how to speed up marsh plant colonization of subsided hayfields opened to the tides. Philip Williams Associates (now part of the environmental consulting firm ESA-PWA) came up with a design that added both sediment and topography to the compacted farm field and also sought to dampen waves across the big fetch of the acreage. To accomplish this, the conservancy arranged to bring 2.5 million cubic yards of dredged material from the Port of Oakland to the site, a first for advocates of beneficial reuse of this material.

Though still a work in progress, Sonoma Baylands is a well-regarded benchmark in the region’s restoration learning curve. Useful debates ensued over how best to connect an inland site to the Bay through an outer marsh, how endangered species respond to restoration actions, and whether to keep tinkering or just be patient and let nature finish the job. And it was the first real kick in the pants for a region reluctant to commit to long-term monitoring and adaptive management. With this project, our naïve love affair with the idea of creating “instant wetlands” and walking away finally ended.

Farther along, the road approaches Sears Point, a 2,300-acre landscape owned by the private nonprofit Sonoma Land Trust. Here the ambitious restoration plan endeavors to nurture a range of habitats from sea level at the Bay shoreline to the uplands of Cougar Mountain, among them tidal marsh, seasonal wetlands, riparian corridors, and grasslands. The plan also preserves some agricultural uses and develops more miles of Bay Trail for public enjoyment. With final permits pending, the land trust hopes to start moving dirt by the fall of 2013.

The next bridge crosses Sonoma Creek, and here Skaggs Island comes up on the left. This ex-military listening post is so big and so centrally located that engineers say opening it to the tides will dramatically change the entire North Bay’s tidal prism–the volume of water exchanged between low and high tides. Right now there’s no funding to test this assertion on Skaggs, but after years of prodding from advocates and the local congressional delegation, the military transferred 3,300 acres of the property to the wildlife refuge in 2011.

Long Time Coming

While Skaggs remains in limbo, the next stop on our drive-by tour, Cullinan Ranch, is on a roll . . . finally. It’s taken two decades to assemble the plans, permits, and partners to restore the 1,500-acre ranch. Francesca Demgen recalls the fight in the 1980s by Vallejo citizens and regional environmental groups to save the ranch from becoming a new suburb called Egret Bay. “People in Vallejo recognized that once city services crossed the bridge over the Napa River, all the oat fields and open spaces beyond would go,” she says. The community not only stopped the development, but also lobbied to get money to buy the property for the public. “It wasn’t just ‘Don’t do this in my backyard,’ it was also ‘Here’s an alternative for the landowner.’ And now, years later, Cullinan is being restored to the tides.”

Cullinan does, however, illustrate the one major complicating factor in most North Bay restoration projects: the need to protect a subsiding Highway 37 and the adjacent rail tracks from flooding. On Cullinan, Ducks Unlimited has just completed a huge setback levee–sloping gently up from marsh plain to elevations out of reach of extreme high tides, and doing double duty as both habitat and flood protection. “Protecting an old elevated highway over the high marsh, while also trying to improve public access from the highway to these marsh areas, has been really expensive,” says Lowgren, “but it’s a must.” This “must” also applies to Sears Point to the tune of an estimated $9 million in infrastructure protection out of a total restoration budget of $11 million.

On Cullinan, Ducks Unlimited is also following in the footsteps of Sonoma Baylands, and using dredged material to make subsided substrate more vegetation-friendly. “We’re struggling to make beneficial reuse cost-competitive with ocean or in-Bay disposal of the material,” says Carroll, who is well aware of new science documenting the increasing deficit in natural sediment supply circulating in Bay waters. Without this supply, restored sites can’t build up naturally to tidal elevations.

Besides a lot of new dirt, Cullinan has a parking area and kayak launch to reward the public for its years of patience and investment. And the tides will reclaim baylands humans long ago “reclaimed” from “useless swamps,” but which are now recognized as the lungs of any estuary.

“Estuaries like this don’t exist in very many places, especially not next to seven million people,” says Lowgren. “We can’t re-create an old-growth redwood forest in 50 or 100 years, but we can do that with an estuary. It’s amazing to think that in my lifetime I’ll be able to come back here and see a mature tidal marsh, much like it was 150 years ago. It’s really rewarding to be part of the solution.”

Lowgren and Carroll are part of a younger generation of “doers” in the local environmental field. They share a fierce intelligence and commitment to the task of undoing the damage of generations past, and they seem to like the challenge. “The Napa salt ponds and the South Bay salt ponds capture our imagination because they’re of a landscape scale,” says another doer, ESA-PWA’s Jeremy Lowe. “They’re places where we have a chance to think about how everything fits together. Working on these landscapes shows us the difference between restoring individual sites and restoring an estuary.”

This is part of Baylands Reborn, a special section in the July 2103 issue of Bay Nature magazine, funded by the following sponsors:

- Cargill is an international producer and marketer of food, agricultural, financial, and industrial products and services. Founded in 1865, the privately held company employs 142,000 people in 65 countries and produces solar sea salt in the San Francisco Bay Area.

- The Coastal Conservancy is a California state agency that protects and restores the natural environment, invests in communities, and helps people get to and enjoy the coast of California and natural lands around San Francisco Bay.

- The Friends of the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge are dedicated to protecting and preserving our amazing San Pablo Baylands, which provide habitat for the endangered California

- Clapper Rail and Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse and serve as a wetland sponge, soaking up sea level rise.

- The San Francisco Bay Wildlife Society is a not-for-profit cooperating association that supports the education and research activities of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and promotes public awareness and appreciation of the San Francisco Bay and its natural history, helping to conserve and preserve Baylands as essential wildlife habitat.

- The San Francisco Estuary Partnership brings together resource agencies, nonprofits, citizens, and scientists committed to the long-term health and preservation of the San Francisco Bay estuary. The Partnership manages or oversees more than 50 projects that protect, restore, and enhance water quality and habitat in the estuary.

- The Wildlife Conservation Board was created by the state legislature to authorize and allocate funds for the purchase of lands and waters suitable for public recreation; for the preservation, protection, and restoration of wildlife and aquatic habitats; and for the construction of nature-based recreational facilities.