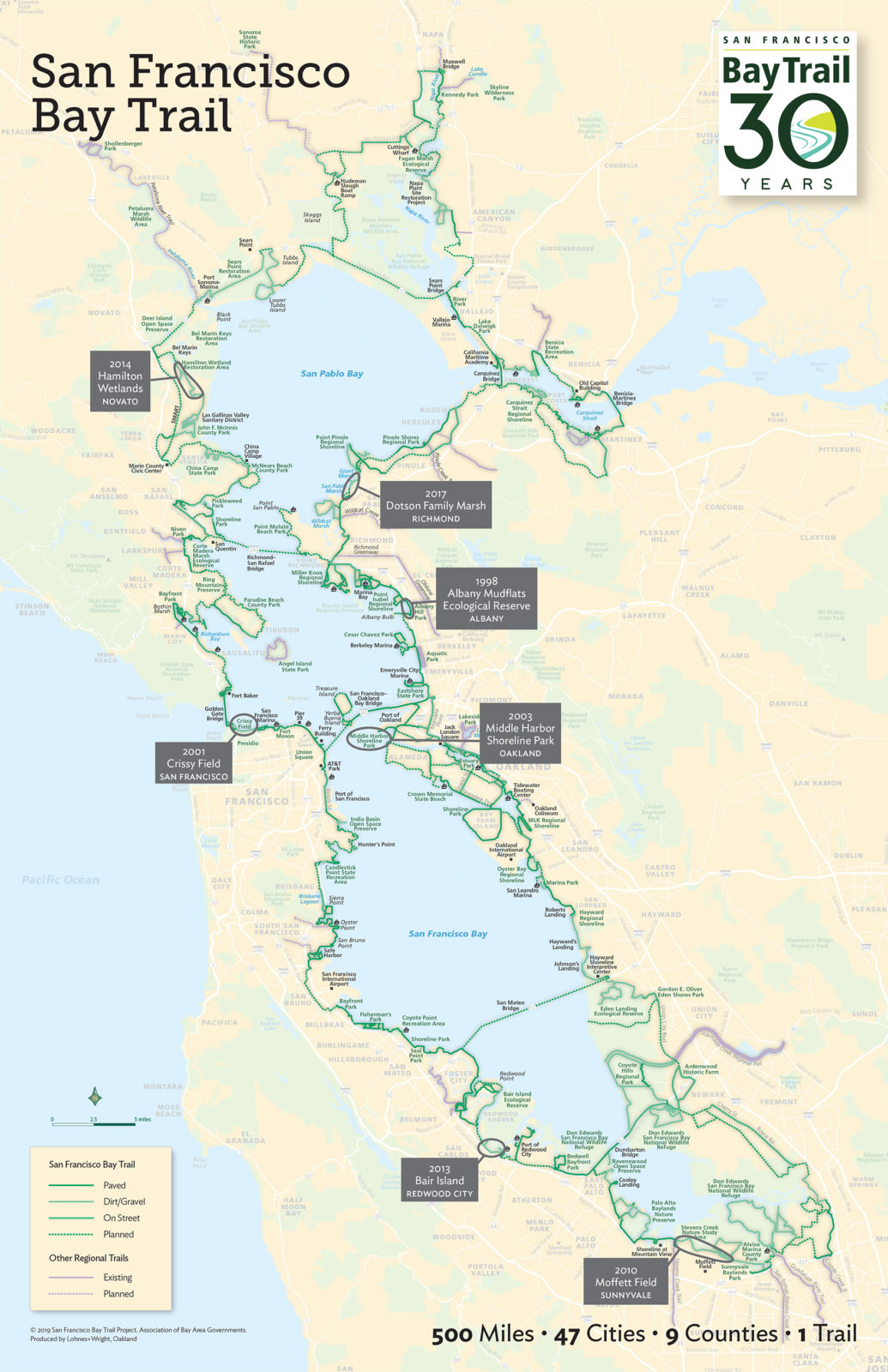

Thirty years after the project officially began, the idea for the San Francisco Bay Trail seems both delightfully obvious and considerably difficult. To link Bay Area communities across nine counties and 47 cities with one multiuse, 500-mile trail is an ambitious dream. And as with other major social initiatives, fully building out the Bay Trail is an ongoing endeavor, decades into its existence.

LOVE THE BAY TRAIL … and help close the remaining gaps.

»Join your community’s trail advocacy group, such as Trails for Richmond Action Committee.

» Ride with your local cycling coalition, like the Silicon Valley or Marin County Bicycle Coalition.

» Clean up the shoreline with organizations such as Coastal Cleanup, Save the Bay, or Audubon Society chapters.

» Become a citizen scientist with an existing project or start one. At Bair Island, visitors can photograph a specific signpost and tag the images with #restorebair1 on Instagram to help track habitat restoration.

» Public-private partnerships improve the trail for all. Is your company near the Bay Trail?

» Local photographers and hikers have documented the entire Bay Trail: walkingthebaytrail.com; rhorii.com/Baytrails.htm; walking-the-bay.com. Could you be the next to do it?

» Tell your elected officials you want a completed Bay Trail, comment on shoreline development projects, and be an involved citizen in your shoreline city.

Even before the vision of a loop trail could be realized, Californians had to get excited about spending time at the shoreline. That required some serious cleanup. In the 1950s, nearly 85 percent of San Francisco Bay wetlands had been destroyed. Residents and corporations dumped waste along the shore or right into the water. Business development had taken over and transformed waterfront areas that had previously been valuable estuarine ecosystems. When the nonprofit now known as Save the Bay was formed in the 1960s, its mission was radical. And over the next few decades, as restoration of the Bay began, the thought of reaching—and spending time on—the shoreline created a new desire for one continuous trail.

What began as a concept bandied about over lunch more than 30 years ago by then–state senator Bill Lockyer of the East Bay has now become part of Bay Area life. Passed into law in 1987, California SB 100 directed the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) to establish a “recreation corridor” that was codified as the San Francisco Bay Trail Plan two years later. The plan also created the San Francisco Bay Trail Project, a group within ABAG that galvanizes and coordinates the many public and private stakeholders that have a role in continuing to build the Bay Trail loop. Crucial among them are three regionwide Bay Area agencies—the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, State Coastal Conservancy, and San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission—that fund the Bay Trail and ensure the project’s implementation.

More than 355 miles of paths so far, the Bay Trail will ultimately connect to more than 130 parks and open spaces. Roughly 230 miles of paved path complement another 120-plus miles of natural-surface trails designed to be suitable for a wide range of uses without harming Bay wildlife and habitat. Other “spur” trail segments at times divert from the shoreline into additional scenic stretches. “The Bay Trail offers people of all income levels and backgrounds the opportunity to get close to the Bay,” notes Rick Parmer, a longtime Bay Trail board member. Indeed, the way that the interconnected, still-in-progress Bay Trail network meanders around the shoreline invites us all to do the same.

1998

Albany Mudflats Ecological Reserve, Albany

A small clutch of birders wait, shielding their eyes from the glare of the sun off the Bay, with binoculars in their hands. Red-throated loons and white-headed mew gulls bob on the water. Suddenly, there’s a mild gasp as a burrowing owl pops up in the cordgrass, and all eyes focus on the small bird’s swiveling head along the narrow band of tidal shoreline west of the Bay Trail.

At low tide, dendritic channels in the mud drain Bay water away from the Albany shore, creating habitat critical for birds, an area where more than 150 species have been spotted. That’s just one of the reasons this 160-acre pocket was designated an ecological reserve by the Fish and Game Commission in 1986. When the Bay Trail began in 1989, there were roughly 120 miles of existing trail; each section added since has a story. The one-mile-long Albany Mudflats stretch, created by Caltrans, was a mitigation for the agency’s expansion of I-80. Stakeholders debated whether to install a high fence along the trail to protect shorebirds or a low one to allow visibility; they compromised by adding a few viewing gaps.

2001

Crissy Field, San Francisco

The sun isn’t even fully overhead yet, but already there is a fragmented line of joggers who head down the path to the turnaround point at “Hopper’s Hands.” The small sign with two big raised hands on it is affixed to the fence at Fort Point along a planned spur of the Bay Trail. Practically begging for a high-five, the sign is such an institution for local runners, walkers, and skaters, it’s almost part of the Crissy Field landscape itself—and a natural extension of the existing Bay Trail here.

It wasn’t always so. When this now-iconic roughly 2.5-mile stretch of shoreline at the base of the Golden Gate Bridge opened in 2001, it was after decades of decay and disrepair. Few beyond devoted boaters would venture there. But in the nearly 20 years since it was reimagined, Crissy Field has become one of the most visited sections of the Bay Trail, a destination within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area for international visitors as much as for locals.

On weekend afternoons, the paths near the Warming Hut Café are clotted with sightseers and fishers headed for the piers. Locals know that weeknights before sundown here offer respite from the crowds. Go just before dusk, and in the 18-acre tidal marsh that flows past dunes and a wide beach (with access mats) connecting to the Bay, you’ll often spot wading herons and killdeer and see a few brown pelicans and Caspian terns diving for fish.

2003

Middle Harbor Shoreline Park, Oakland

The last lights went down on the amphitheater main stage, and the Blurry Vision Festival’s headlining artist SZA gave one last shout-out to Oakland before she departed. As the crowd of festivalgoers dispersed, colorful cargo boxes the size of semitruck trailers stood as reminders of Middle Harbor Shoreline Park’s previous identity.

Situated within the Port of Oakland, the Oakland Naval Supply Depot closed in 1998 and was later reconceived as this 38-acre urban park, with grassy lawns and a concert stage that make it a popular festival venue. Community and environmental groups worked with the port for more than six years to restore natural habitats for wildlife and create an attractive public park that serves locals, Oakland’s students eager for outdoor education, and entertainment groups keen to bring major live music events back to this part of the East Bay. “This is a park unlike any other,” says Port of Oakland environmental programs and planning director Richard Sinkoff.

The park offers a full-service stop along the Bay Trail, with amenities and views along the Oakland shoreline, especially if you climb the Chappell R. Hayes Memorial Observation Tower, named for the late West Oakland environmental activist. Watch for California least terns foraging in the shallow waters; one of the largest colonies of the endangered seabirds is located at the nearby Naval Air Station Alameda. You can even take a dip in the Bay at what was, when it opened in 2004, Oakland’s first public beach. If you do wade in, watch for passing schools of marine fish and, in season, Dungeness crabs scavenging in the eelgrass shallows. On weekends without any scheduled events, the area is rarely crowded.

2010

Moffett Field, Sunnyvale

It’s midmorning before the bike traffic starts to thin along this unlikely commuter stretch of Bay Trail just south of where Stevens Creek feeds into the Bay. These 2.25 miles of shoreline follow restored wetlands—where black-necked stilts, great blue herons, and western sandpipers forage—along South Bay salt ponds, an easy distance from several corporate campuses that line the waterfront. Formerly owned by agriculture giant Cargill, the land was sold to NASA in 2002, at which point more than a dozen city and regional agencies worked together to open this long-missing link between Sunnyvale and Mountain View; it now connects 25 miles of contiguous Bay Trail from San Jose all the way to East Palo Alto.

In the same ways that wildlife returns to restored wetlands, people have populated this vital section of Bay Trail since it opened in 2010. Google signed a billion-dollar 60-year lease on Moffett Airfield with NASA in 2014, and the paths were resurfaced with packed gravel, providing the bike-commuting workforce and the public with a long, smooth ride or walk along the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, which is governed by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “A lot of [Silicon Valley] employees use the trail to walk and think during lunch,” adds Julia Miller, the former mayor of Sunnyvale, who was instrumental in opening the Moffett Field segment. “It’s a very peaceful atmosphere.”

2013

Bair Island, Redwood City

In the 1980s, Redwood City residents Ralph and Carolyn Nobles organized local community members to form Friends of Redwood City to stop a development project at Bair Island, a historic tidal marsh that had been diked and used for cattle grazing and salt evaporation ponds since the early 1900s. An avid boater, Ralph was inspired by his view of the shoreline from the Bay, where he could see harbor seals swimming, cormorants sunning, and egrets and curlews wading in the channels.

Friends of Redwood City staved off development plans again in 1997, and the Peninsula Open Space Trust purchased Bair Island for $15 million, turning it over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The decades-long restoration of Bair Island is an exemplar of the public-private collaboration necessary to construct the entire Bay Trail. Projects that in later stages become cooperative multiagency efforts often begin with individuals like the Nobles or small community groups, who have a distinct vision for the shoreline.

Three parcels form this 3,000-acre tidal wetland within the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge: Outer, Middle, and Inner Bair Island, the latter open since 2013. Inner Bair Island, accessed by a bridge over Smith Slough, has a viewing platform at the end of a short 0.35-mile path. Venture 1.7 miles along a Bay Trail spur for views from an observation deck, overlooking mudflats filled with wildlife.

2014

Hamilton Wetlands, Novato

The massive five-mile pipeline pumping sediment into the Hamilton Wetlands stretched all the way across the Bay, from Oakland to the Novato shoreline. In the restoration area in Novato, the heavy tube sat on tall, sturdy bricks off the ground to avoid disrupting endangered marsh species, including the elusive Ridgway’s rail. The former airfield could only be restored if raised to marshland level, allowing plants to take root. Across the water, the Port of Oakland desperately needed to be dredged. A vision shared by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the California State Coastal Conservancy, which manages the area, helped move 5.6 million cubic yards of sediment to 650 acres of restored plains. When it was completed, it was the largest-ever restored wetland project using dredged material in the nation and included a 2.7-mile section of the Bay Trail.

Three out-of-the-way gravel trailheads are adjacent to residential neighborhoods, as well as U.S. Coast Guard grounds. For easiest access by car, park in the lot at the southern end of Hangar Avenue and ascend a low slope to the levee trail. You’ll no doubt encounter swooping sparrows and soon spot avocets, dowitchers, and godwits scooping and poking at the marsh mud. In the scrubby heath and pickleweed, several types of Anatidae family waterbirds—ruddy ducks, northern shovelers, and cinnamon teals—take shelter. Groves of native California black, coast live, and valley oak trees offer small sections of shade along the mile-long path. At the end, an observation area offers 180-degree views of the former agricultural fields, now a lushly regenerating regional destination.

2017

Dotson Family Marsh, Richmond

This 238-acre parcel of coastal prairie and restored wetland exists due to a generation’s efforts to save it from development. Longtime residents of Parchester Village, the 1950s post–World War II housing development in Richmond, including the Dotson family, spent several decades forming alliances with local groups, including the Sierra Club, to enshrine public access to this unique waterfront area.

In 2008, the East Bay Regional Park District acquired the land, formerly called Breuner Marsh, from a developer owner who had illegally destroyed much of the wetlands habitat. Since then, more than 10 agencies, including the California Coastal Conservancy and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, contributed $14 million to restore the 150-acre marsh within the Point Pinole Regional Shoreline. The area is a striking example of sustained, cooperative efforts to preserve shoreline public access and of the commitment it takes to open a new 1.5-mile section of Bay Trail. When you visit this charming marshland, keep an eye on the skies. You might spot the area’s resident rodent-eating raptor, the white-tailed kite.

MORE BAY TRAIL COMING SOON

»Golden Gate Fields

“Every mile we add now is so important to the big picture,” says Rick Parmer of the Bay Trail board. Indeed, this coveted one-mile section of shoreline has long stymied efforts to link contiguous sections of the eastern Bay Trail. But by the end of 2019 the East Bay Regional Park District will open that Golden Gate Fields segment, marrying paths from as far south as the Bay Bridge to the Albany Mudflats—the section that opened shortly after the start of the Bay Trail project’s slow and steady 30-year effort to unify the region by trail.

»Richmond-San Rafael Bridge

A four-year pilot program will create a 10-foot-wide protected path across the bridge, separated from freeway traffic by a movable concrete barrier. This six-mile segment, expected to open in 2019, will become the sixth toll bridge to join the Bay Trail.

»Corte Madera Creek

An important bicycle and pedestrian bridge near the Larkspur Ferry Terminal will be widened to 12 feet across and be open in 2020.

»Ravenswood Bay Trail

This small but mighty 0.6-mile Bay Trail segment will unite 80 contiguous miles of trail, from Bedwell Bayfront Park south to Alviso and across the Dumbarton Bridge to Fremont. Pending construction permits, it’s slated to be completed in 2020.