We’re peering down into a ravine carved out by Lagunitas Creek, looking for North American river otters. According to official California Department of Fish and Wildlife records, last updated in 1995, we are officially fools; there are no otters anywhere near here. They are “non-occurring,” wiped out from most of the Bay Area long ago by trapping, pollution, lack of prey, loss of habitat—any and all of the difficulties that wild animals contend with in urban areas.

But according to the data collected in the last four years by Megan Isadore and her corps of citizen otter spotters, these little fish-eating predators are all over the place, particularly here in Marin County. On the website of her small nonprofit River Otter Ecology Project, the reports of sightings pour in, from anglers and dog-walkers and nature lovers and amazed suburbanites: Hey, I just saw an otter! As of 2016, ROEP has catalogued more than 1,730 sightings and added to that tally close to 5,000 camera-trap videos and photos and roughly 1,300 samples of otter scat.

And this just seems like an ottery kind of place—a creek full of fish and crayfish, banks dense with shrubby growth, a place that feels wild enough for a sneaky little carnivore to hunt and hide and play. Isadore and her volunteers-in-training, Emma Sharpe and Jeffrey Wang, current and former wildlife biology students, crane their necks over the embankment. Nothing here. But farther up the path, in an outfall below a big dam, we find a tidy pile of fresh scat, the highest standard of otter evidence. Yes, they’ve been here too.

Isadore saw her first otters in 2002, in the moonlight on a tributary of Lagunitas Creek. Soon they seemed to be everywhere, and yet, officially, nowhere.

The fact that otters are back in the Bay Area of their own accord without any reintroduction program to help them looks like a reason to declare victory. It seems to be proof that cleaning up watersheds makes a difference, that restoration works, that species will bounce back if we only push hard enough. “Their recovery in the Bay Area is, I believe, the result of conservation and restoration activities: the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, all these things we did that had a positive effect,” Isadore says.

An otter seems to live for pleasure, gliding in and out of the water, rolling and romping, loudly crunching on crayfish, clowning around. That this joyous creature has returned to the Bay Area seems like sweet reward for the years of hard work by conservationists and environmentalists, a sign that we won—won the wriggly, furry, goofy jackpot.

But in truth, it’s not yet clear how many local otters there are or why they came back, which means no one has determined how to protect or maintain them here. That’s why Isadore launched ROEP. “We don’t know where they are, how many, whether populations are increasing or we just think they are,” she says. “That was the impetus.” If people have the general impression that there are a lot more otters around than there used to be, and in places where they weren’t seen before, that’s one thing. It’s far more useful to have data—systematically collected evidence. With only a minuscule budget, ROEP depends on the natural charms of otters and the enthusiasm of volunteers to collect as much high-quality information as possible.

There’s reason to think the return of the otters may be tenuous. That’s why these three are clambering up and down banks, climbing under docks, exploring culverts, poking every bit of scat along the way. Can we breathe a sigh of relief? Are the otters here to stay? We don’t yet know.

Sharpe and Wang put fresh batteries and data cards into a motion-sensitive wildlife camera and strap it to a redwood tree near the outfall. Isadore demonstrates how to scoop up bits of fecal material into glassine bags for future study. These two volunteers, and dozens more, will revisit this spot and others for the rest of the summer and into the autumn, wading up and down Lagunitas Creek, scouting out lagoons and beaches, kayaking and biking to remote field sites. This is the slow, painstaking work that can begin to explain the return of the otter.

A North American river otter weighs on average 20 pounds and is roughly three feet long from extremely whiskery front end to oddly flattened tail. (“Much smaller than you’d think,” Isadore says.) It features what must be the most boopable snoot of any mammal, a large flattened moist “rhinarium,” or nose pad. A river otter is a mustelid, like a weasel or a badger. But in terms of physique, it splits the difference between land and water mammals. It swims and runs passably well but is neither as adept as a seal in water nor as stealthy as a mink on land. With no blubber, it relies on a dense, luxurious coat of fur to stay warm. As it humps along a shoreline, the overall impression it creates is something like a Slinky in a fur coat.

Until 1961, river otters in California were trapped for that fur. In Humboldt and Mendocino counties up north and in the Delta, otters managed to hang on. But from San Francisco Bay south, they vanished.

Hunting was probably only part of it; water pollution may have been a big reason for the decline. Pesticides, heavy metals, and other water pollutants can make otters sick, reduce their breeding success, and kill off the fish they depend on. The Eurasian otter offers a useful comparison. In southern England, those otters vanished even though they were never hunted, apparently due to pollution such as mercury and organochlorine pesticides like DDT derivatives, dieldrin, and lindane. Once the rivers were cleaned up, the otters came back.

In the Bay Area, rumors of river otter presence began in the late 1980s, but there was no bulletproof sighting until Rich Stallcup, a founder of the Point Reyes Bird Observatory, spotted them just south of the town of Tomales in 1989. (“I was stoked and elated to find three of these excellent creatures,” he wrote.) They might have arrived from the Delta or possibly from up north. Either way, it was surprising but not shocking: River otters are known to travel long distances, particularly when young males disperse in the spring, while water runs high. They follow creeks, even through culverts and tunnels, but will also cross dry land; they might have even hopscotched down the coast.

Isadore saw her first otters in 2002, in the moonlight on a tributary of Lagunitas Creek. Soon they seemed to be everywhere, and yet, officially, nowhere. River otters aren’t endangered, so they aren’t a focus of conservation money and planning. But Isadore knew that without collecting baseline data on them, it would be impossible to monitor them—to know if their populations were increasing, stabilizing, or crashing, or to come up with plausible ideas about why.

She realized someone would need to step up in order to make sense of what was really going on. Isadore had worked with SPAWN, a salmon-restoration nonprofit in Marin, for 13 years, learning field biology and stream ecology and eventually becoming lead naturalist. Focusing on otters seemed to be the obvious next step for her. “The vision was to establish where they were in the Bay Area, and then do population studies,” she says. ROEP began in 2012 as a science-based, data-gathering organization. Her co-founder Paola Bouley, a wildlife biologist, was the first executive director; Isadore’s husband, Terence Carroll, a longtime conservationist, would be president.

Isadore and Bouley also banked on otters’ natural charms as a great way to get Bay Area residents invested in the watersheds in their backyards. “The river otters are such perfect ambassadors, because they’re so playful and adorable, and a little bit elusive,” she says. (People who study otters, unlike other biologists, don’t even pretend that their subjects aren’t cute.) Otters could be a gateway drug.

ROEP now counts otters in two ways. Anyone can report an otter sighting online by providing enough details to rule out mistakes. But that only tells you where otters are. In order to get other dimensions of information—what they’re doing, what their niche might be—the group also trains and sends out volunteers who visit specific field sites weekly throughout the summer and early fall, when mothers have brought their new pups out from their dens and most other otters tend to stay put in their territories. Using an app designed to capture otter data, volunteers record the locations of signs (latrines, paw prints, tail drag marks, slides, dens), maintain motion-activated camera traps, and review the footage to document family life and behavior. (The cameras have caught other creatures too: bobcats, a badger, a merlin, baby foxes, and once a woman skinny-dipping.)

This method provides a more granular view of otter life across various shorelines of Marin, stretching from Rodeo Lagoon just north of the Golden Gate, along the Pacific up to Abbotts Lagoon, including sites along Tomales Bay, all the way up Lagunitas Creek to the reservoirs, as well as other marshes, lakes, and creeks. Volunteers also gather scat samples for two projects: monitoring for Vibrio and Salmonella—bacteria common in other aquatic mammals—and DNA analysis.

Some sites are wild, but others are right off of major roads, because otters can put up with quite a bit of human contact. In the East Bay, they loll around in Oakland’s Lake Temescal, in the shadow of two freeways. One has been seen at the lake next to the Hilltop Mall in Richmond. And then there was Sutro Sam, who took up residence at San Francisco’s Sutro Baths in 2012. He spent months devouring the fish in the ponds there, undeterred by the legions of fans who came to see him, some bringing trout from the nearby Safeway. It wasn’t until the fish ran out that he left.

Out in Point Reyes National Seashore, Isadore has her own field site at Abbotts Lagoon, where salt water and fresh water mix down near the sea. We’re walking along a trail toward a passage between two lagoons when Isadore suddenly stops and hisses, “Look! Otters!” The carpet of whorled marshpennywort in the shallow end of the lagoon quivers. Then suddenly a lithe brown body bursts from the water and lopes up the steep sand dune. It’s followed by another, and then another, and now there are six—a carnival of otters snorting and rolling in the sand. We have a perfect view of them, and it’s hard to know where to look amid the frolicking.

Two slink their way up the slope, inspecting a latrine where other otters have left their scat. One defecates with great enthusiasm, waggling its hindquarters vigorously and stamping its hind feet. The other toboggans on its belly down the dune into the water, and then, just as abruptly as they appeared, this tangle of sleek brown creatures is gone.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

TO SPOT AN OTTER

Want to spot an otter? When you’re near a shoreline — a wetland, creek, lake, bay, or the ocean — look for the following tracks and signs. And then keep your eyes open for a fast, sinuous motion in the water, at or just below the surface.

Tracks

A perfect set of river otters tracks will show the webbing between its toes and the indentations from its nails. The back paws are slightly larger than the front. Also look for a thick, long drag mark behind the tracks made by the otter’s tail.

Slides

Otter slides can be spotted in sand, grass, mud, and even snow. Depending on the frequency of use, the slides can range from roughly 8 to 12 inches wide and be as long as 25 feet.

Scat

Otter scat can vary in shape from a tube to a patty, but it is almost always full of fish scales, and smells, well, fishy. It is frequently found on top of soil or debris mounds.

They’re Everywhere

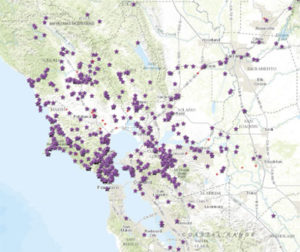

The River Otter Ecology Project maintains an interactive map of Bay Area otter sightings reported by citizen scientists. To expand the map and read about each submission, or even submit your own sighting, visit the ROEP online.

Photos (from top): Sharron Barnett, marinnature.com; Scott Doniger; Kim Cabrera.

Map courtesy River Otter Ecology Project

Three of the group are now hunting the shallow water along the edge, and we follow parallel on shore to watch. We see nostrils, eyes, whiskers, and teeth, then the curve of a small back as it dives. One surfaces, making plaintive little peeps. Another pops up to devour some prey, crunching away like a svelte brown Cookie Monster.

Based on their sizes and contact calls, there could be two adult females accompanied by a few new pups, Isadore guesses. The other two could be last year’s pups, or even older daughters. (Otter family composition is flexible but generally does not include fathers, who leave after mating.) Each season is its own little mystery; as Isadore watches this group over the summer she’ll gradually figure out who is related to whom.

With otters, there aren’t many rules. They do perfectly well alone, but loose groups are also common; they tolerate one another, sharing overlapping turfs, and may even hunt cooperatively. Males may form “bachelors pods” of as many as a dozen, hanging out together for otter parties: piling up vegetation to pee and defecate on it.

Otters hunt at night, or at dawn, or during the day. They’re smart enough to target particular species when they know those fish are sleeping. They prefer shallow areas, but will hunt any area with easy-to-catch fish—streams, lagoons, ponds, estuaries, even the ocean. They often rest on banks with shrubby, dense growth, but will nap on a beach if they feel secure. In general, they stay close to shore; theirs is a linear world, a thin boundary strip of water and land.

The only unbreakable rule of being a river otter is to eat a lot. These creatures consume 12 to 15 percent of their body weight each day—far more than most mammals of similar size. So although they prefer fish, they’ll eat nearly any meat, including frogs, crayfish, shellfish, insects, small mammals, and birds. ROEP volunteers find the feathers of pied-billed grebes, coots, and cormorants in scat; at Rodeo Lagoon, otters have been witnessed killing brown pelicans.

These little carnivores live on a metabolic knife’s edge, suggest studies conducted by Hans Kruuk, honorary professor at Scotland’s University of Aberdeen and perhaps the world’s preeminent otter expert. To eat, they must swim in cold water. To stay warm without blubber, they must fuel the body furnace with calorie-dense food. Otter life is a Catch-22 of hunting to stay warm and staying warm to hunt. On top of that, otters have a low reproductive rate, with an average of only one to three pups a litter, and they generally don’t breed every year. And many river otters have short lives. While they can live as long as 25 years in captivity, the median age of a population in Prince William Sound in Alaska was only four years. The average annual mortality for adults is about 27 percent, according to one study in western Oregon.

This is why it’s so important to know more about Bay Area otter populations, says Isadore. What kinds of fish do they depend on? Are they breeding successfully, and how often and where? In an otter’s life, there’s little room for error. Given their extraordinary metabolisms, they require plentiful prey and may be particularly sensitive to slumps in fish populations that occur as a result of climate change or other shifts.

It’s important to know how many otters are around for the sake of other creatures as well. Top predators, they scarf up crayfish and fish, particularly slow bottom-dwellers like sculpin. “They eat them like potato chips,” says Isadore. For that same reason, otters may be a boon to other species. Eelgrass beds provide nurseries for many baby fish, including salmon smolt. As otters prowl through the eelgrass, they ignore the tiniest fish, but snap up the bigger fish that prey upon the little ones. The impact of otter predation on Bay Area ecosystems is unknown and is another subject Isadore would like to study.

How they interact with other animals is likewise not very well known. Coyotes might prey upon otters under some circumstances, but the interactions between the two are not always straightforward predator-prey relationships. One of Isadore’s most fascinating camera-trap videos captures the meeting of an otter and a coyote. The coyote trots across the otter’s beach—her territory. The two circle one another on the sand, then chase each other round and around a rock, just like in a cartoon. Are they threatening one another? Checking each other out? Neither one looks frightened. Rather, they both seem wary, but curious—maybe even a little bit playful.

Isadore has shown the video to several otter specialists, and none of them were sure what’s going on either. “We can’t bring ourselves to say, ‘Yes, they’re playing,’” she says. “But we all want to.”

We leave the otters to their breakfast and return to the dune; Isadore is eager to get some of this supremely fresh scat.

For the record, otter fecal material does not smell like the turds of carnivores you may be more familiar with. It has a musky, fishy, wild aroma, not unpleasant if you don’t mind the smell of low tide, and it’s flecked with fish scales and bits of shell. Otters also excrete a jelly-like substance that apparently protects their guts from sharp shell fragments and fish bones. There’s plenty of that stuff here too, looking like blobs of blackish Jell-O. Isadore scoops up some as well.

A key thing to know about river otters: Excretions are a very big deal for them. Latrines are communication stations, where animals frequently stop by to leave small symbolic fecal deposits, make scent secretions using the glands in their hind feet, and investigate what else has been left behind. (Kruuk reckons that no carnivore produces scent-mark feces more frequently than an otter does.) It’s sort of an otter Foursquare: a brief record of who was here and what they had for lunch.

Consequently, otter scientists are also deeply interested in poop—examining it, testing it, even playing tricks with it. In one set of experiments, Humboldt State University wildlife biologists Jeffrey Black and Alana Oldham added scat from faraway otters to a local latrine, then documented the response. When the regulars returned, they obsessed over the foreign poop, investigating it and covering it with their own. “There were 20 times as many paw prints, all around the new scat,” says Black. “They pee on top of it, and leave their own scat.” Exactly what otters learn from scat is not clear, but it might include gender, hormonal status, and other updates.

For scientists, these deposits provide a dietary record; researchers dig through scat for otoliths, the characteristic bony structures in vertebrate ears, to identify which fish species otters eat. With other kinds of testing, scat can reveal pollution exposure or, through DNA analysis, a map of genetic relationships.

So researchers like Isadore are thrilled when they find brand-new scat—it’s a bigger database with more information. Usually that’s left to chance, but one enterprising Canadian research group developed a way to identify the freshest, most testable scat by scattering latrines with a layer of glitter. The next day, new productions would be obvious: glitter-covered scat was old; scat without glitter was new.

But poop is just part of otter science. Ideally, the information it yields is combined with other types of data. More than 15 years ago, Black began the first otter-spotter project in California in Humboldt and Mendocino counties. Sightings from his spotters, primarily former biology students, anglers and outdoorspeople, are cross-correlated with scat DNA analysis. With this two-dimensional method, Black found a high density of otters in Humboldt Bay, somewhere between 41 and 44 in a study area stretching along 28 miles of coastal habitat. Importantly, the genetic data suggested that the otter-spotter data alone undercounted this population considerably. “What we learned is that citizen scientists are seeing about 50 percent of what’s really out there,” he says; the information is really just a pointer to where otters are, not a full census.

ROEP doesn’t yet have the resources to execute such a study, but it has pulled together results from its citizen science and trained volunteer projects in a paper published last year in Northwestern Naturalist. The upshot: Otters have been spotted in every county of the Bay Area except San Mateo. The ROEP study area of Marin County hosts approximately 50 otters total, with a minimum of 0.21 otters per 0.6 miles along the coast from Rodeo Lagoon north and a higher density in Tomales Bay alone, at around 0.32 otters per 0.6 miles. (There was less data on inland regions along creeks and in reservoirs, so population density was not calculated for those areas.) These densities are minimum figures. They’re lower than Black’s and could reflect a rebounding population, or they could be an underestimate.

More data will come from a genetics study now under way; Jordan Arce, a graduate student at the Genomics/Transcriptomics Analysis Core at San Francisco State University, is using scat samples to measure the genetic diversity of North Bay otters. The analysis will estimate the male/female ratio and will read mitochondrial DNA, tiny loops of genetic material passed from mothers to offspring that can be used to estimate the relatedness between individuals. Roughly speaking, more diversity and less relatedness indicates a healthier population. “It can tell us a great deal about the status of the species and how it’s functioning, and also the status of the ecosystem,” says Arce.

By comparing samples from four sites in the North Bay, he also intends to figure out how groups are related—and by implication, how otters have spread. Samples from Sutro Sam, for example, could confirm whether he arrived in San Francisco from the Marin Headlands, as Isadore suspects, or from the Sacramento River Delta. It seems likely that East Bay otters came from the Delta, but determining that for sure is a project for the future.

Meanwhile, Isadore is making sure the data she and her crew have collected gets on the desk of anybody who might need it for management decisions. Knowing where otters are is important for many reasons—for example, protecting endangered species that can be otter food, like coho salmon or the chicks of Ridgway’s rails. The data is also needed to prepare for oil spills, says Michael Ziccardi, director of the Oiled Wildlife Care Network at UC Davis, which coordinates the responses of dozens of organizations statewide.

With a considerable increase in the amount of oil being shipped via train into Martinez and other sites near the Bay, a spill becomes more likely—but without accurate maps of otter populations, a rescue response might be inadequate. Otters are highly sensitive to spills: Not only does oil kill off otter prey, an otter with oiled and matted fur will soon be too cold to hunt. “Knowing that otters are in the general vicinity is of value, but the more fine-grained data that we can have, that can help us know where priority areas are should a spill occur,” Ziccardi says. After the Cosco Busan oil spill in 2007, otters were seen feeding on oiled pelicans. But with no census from before the spill, it’s impossible to know whether their population in the Bay Area took a hit—or how bad it might have been.

Otters are usually their own hype men—they need no support. But this is a tough crowd here at the Star Academy, a high school for students with learning differences in San Rafael. These ninth and tenth graders and their teachers have been monitoring a nearby site all year. Isadore is coming to thank them in person.

She cues up a video—a series of camera-trap clips of otters playing, snuffling at the camera, and generally being irresistible. It’s followed by a beautiful animation. But she gets only a few laughs. It’s June, and these kids just want the school year to be over.

We all go out to the site, at Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District reclamation ponds, to look for otters and their evidence. As they walk the dirt roads, the students brighten up. One of them, a student, tells me he’s become expert at otter detection: “I can walk right up to it and know it’s scat.” Others goof around, imitating the death throes of the grebe they saw get killed by an otter earlier in the year.

This spring will be ROEP’s five-year anniversary. In 2014, Isadore was awarded the Environmental Leader of Marin gold medal; the group won a conservation award from the John Muir Association. But documenting otters in the Bay Area is only phase one.

There are now more new questions to answer. There are hints that river otters on the coasts have distinctive patterns, habitat needs, and diets. Researchers want to learn more about that. Will they keep spreading southward? Last year brought one unconfirmed sighting in the Santa Cruz Mountains and one in Los Gatos, around Vasona Lake. Historically, otters were found all the way down to San Luis Obispo.

Isadore sees otters as a way in to understanding relationships between other things—how otter prey like the endangered coho rise and fall, whether local improvements in water quality outweigh the new pressures of climate change for otters. As an animal that relies on land and water, fish and fowl, it’s a species that can tie a lot together.

She’s plotting to do a study to link pollutant loads around the Bay with otter reproductive success, reading river otters like a sentinel for water quality. “River otters are an enormous treasure chest of information,” she says. “I’m impatient to have the staff and the money to do all these studies and drill down into it.”

Because it’s not enough to celebrate that otters are back, she says. “Too often people in conservation, people like us who live in this beautiful area, we can get a little bit insular and pleased with ourselves. We can look around and say, ‘We live in paradise and we’re fixing it!’ We have to do more.”

She’s counting on the otters to do it. And they work in mysterious ways. As we walk along the berms with the Star Academy students, one girl sidles up alongside Isadore with a question. Earlier, she looked bored. But now she wants to know: Could she get a copy of that video, the one with the gorgeous animation? She wants to be an artist, the student says, and someday make videos like that one.

That’s how it works, Isadore says later: Efforts have ripples and consequences that you never anticipate. By showing a high-school student a video, you might awaken an interest in art and environment. By cleaning up a watershed, you just might find yourself surrounded by otters. “I want people to understand we have the ability to work for positive effects, as well as [have] the negative effects,” she says. “I want people to believe we have the ability to change things. That’s what I’m constantly trying to get across.”