Tucked away in a back corner of San Francisco’s Presidio, below the bluff where Inspiration Point gathers itself into the Tennessee Hollow watershed, the legendary waters of El Polin Springs still run.

They drain from the headwaters through deep fractures in the underlying serpentine, charged by winter rain and diminished by summer drought, braiding themselves into three distinct threads, of which El Polin is the only one with a name. Here the water tumbles over colonial-era brickwork in a seasonal cascade that oscillates with the year: abundant in April, a trickle in October. Scattered stands of willow and wax myrtle mixed with native clovers and rushes testify to the high water table here; no other site in the Presidio has a greater diversity of birdlife. Hummingbirds buzzing in the bee plant lend the tableau an erotic air, while the voice of the spring as it pours from the earth tells the story of all that renews itself in nature.

Whispers about this place have permeated San Francisco history from the earliest times.

When Captain Anza claimed this land for Spain on founding the Presidio in 1776, small settlements of Ohlone still lived beside the three shifting freshwater springs that flowed at the base of the steep elevations less than a mile southeast of the main post site. A legend began to circulate among the conquistadores about one of those springs, where the waters were so magical that any maiden who drank from them (especially under a full moon) obtained great fertility and was sure to have an abundance of twins, while any man so imbibing enjoyed a jolt of pre-Columbian Viagra. The Spaniards called this potent wellspring El Polin, after their word for the great phallic rollers used dockside to load cargo aboard ships. Sources hint at Ohlone origins for the legend, but the nickname is 100 percent macho Spaniard.

On taking command of Alta California in 1794, Governor Diego Borica remarked upon the general fecundity of the Bay Area, citing El Polin as the freshwater spring in the Presidio to whose marvelous virtues he attributed the large families of both the Spanish and the Ohlone. He noted that the spring and its qualities were known to the Indians from a remote period and were famous throughout California. Recalling this, Mariano Vallejo wrote in his 1876 Discurso Historico: “It gave excellent water of miraculous qualities. In proof of my assertion, I appeal to the families of Miramontes, Martinez, Sanchez, Soto, Briones, and others, all of whom several times had twins; and public opinion, not without reason, attributed these salutary effects to the water of El Polin.”

Today, El Polin seems more forlorn than fecund. At the spring itself, the water falls from its brickwork cascade and meanders across a lonely picnic area into a dilapidated cobblestone well, where vandals have stolen the copperplate sign that summarized the Spanish legend. A few barbecue grates and tables stand nearby, usually empty. The water trickles away for another 20 yards or so, then falls into a drainpipe and disappears beneath MacArthur Avenue.

It was not always so. Layered beneath these recent decades of obvious neglect, artifacts recall a long history of humans living here in harmony with the natural environment. And today’s Presidio, busy reconfiguring itself from military base into modern urban national park under the aegis of the Presidio Trust, aims to preserve the post’s architectural character, endangered species, and open space while still accommodating the recreational needs of the public and the commercial demands of financial self-sufficiency.

That complex mandate includes an ongoing effort to restore parts of this landscape to some semblance of former glory. In Tennessee Hollow, the park’s largest watershed at 270 acres, land managers seek to rehabilitate an entire riparian system—from the remarkable serpentine grasslands in the headwaters that host the endangered Presidio clarkia, to El Polin and other seasonal springs, all the way down to the bayshore drainage at Crissy Field, the Presidio’s signature restoration project.

“This is a unique chance to restore nearly an entire watershed in the city,” says Peter Brastow, director of the nonprofit Nature in the City and a member of the Presidio’s Environmental Council. “It is developed, yes, and has a long history of disturbance, but still this is mostly open space where we can restore a healthy indigenous ecosystem.”

The Question of Landscape Design

We humans have always shaped the land surrounding our settlements, even as the landscape shapes us. Evidence shows that the Ohlone burned grasslands (such as those found at Inspiration Point above El Polin) for hundreds if not thousands of years to maintain an abundant supply of grass seed, the principal ingredient of their food staple called pinole; to promote edible bulbs like soaproot and Ithuriel’s spear; and to prevent the succession to coastal scrub, a less productive plant community. Native American burns were outlawed by decree of the Spanish governor of California in the late 18th century, and legal deeds from that time forward document the manipulation of the landscape for agriculture and animal husbandry. Early in the 19th century, members of the Miramontes family built their adobes beside El Polin Springs, planted orchards, and raised cattle. They kept a house here into the early 1850s, when they were evicted by the U.S. Army.

Almost immediately, the American military set about transforming much of the Presidio’s landscape. This sandy, windblown environment posed logistical obstacles, so quick-fix decisions pulled rank. In the 1880s, thousands of blue gum eucalyptus were planted into the headwaters of the Tennessee Hollow Watershed as a fast-growing windbreak and a symbol of military might; these thirsty “historic forests” now suck the water table dry, and their acidic fallen-leaf-and-bark detritus blankets the understory, choking out native plants. “Fill Site 1,” a midcentury landfill cradling El Polin to the southeast, contains hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of mostly unknown composition but confirmed to include medical waste dating from World War II, cyanide, lead, and other toxic surprises; “Landfill 2,” another huge deposit of mystery contents, lies southwest of the spring and Inspiration Point, forming part of the headwaters of El Polin.

That toxic soil lies like a wet blanket over a long history of interwoven human and environmental threads, raising an interesting angle on the question of restoration: which layer of the palimpsest shall we bring to the surface? And what shall we contribute to the long and complex chronicle of human use and stewardship of El Polin and its watershed?

A Woman Ahead of Her Time

Recent investigations have peeled back the veneer of military history to reveal some of the site’s more distant past. Archaeologist Barbara Voss and her team from Stanford University have conducted several digs here, sketching in details from the early years of the colonial era and, especially, from the life of Juana Briones, a fascinating character who helped shape both the culture of the early city and the physical contours of El Polin.

Briones lived at El Polin Springs starting from the 1820s, when Mexico first gained independence from Spain. Her mixed-race parents (African and Hispanic) emigrated from Baja with the Anza expedition, and had three daughters born up north. Juana’s older sister married a soldier named Miramontes, and in the mid-1810s they moved to El Polin Springs, where they are the first recorded residents.

Juana married a Mexican Indian footsoldier in 1820; both were illiterate, signing documents with the mark of the cross. They lived in the main quadrangle of the Presidio for a few years, then moved in with the Miramontes family at El Polin.

Despite her lack of education, Juana soon emerged as a leader, obtaining first more land to expand the family’s orchard and ranching enterprises, then a commercial lot in the newly established pueblo of Yerba Buena (now San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood) to sell beef, milk, fruit, vegetables, and medicinal herbs. She soon developed a reputation in town as an experienced midwife and healer fluent in African and Mexican Indian ethnobotanical traditions, and her business prospered.

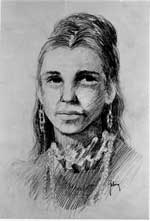

- The only known representationof Juana Briones, based on her niece, who was thought to look much likeher. Photo from the collection of the Los Altos History Museum.

Her marriage, alas, did not enjoy similar success. In 1844, after 24 years of abuse by a drunken husband, she petitioned for ecclesiastical separation, a feminist feat of unprecedented audacity for that time; she henceforth used only her maiden name and was referred to as a widow. Undeterred in her ambitions, she used the proceeds of her businesses to purchase ranchos and residential lots in present-day Los Altos, Santa Clara, and Palo Alto, where she and her sisters and daughters built homes. They lived as women independent from men, led by Juana “with no help from a worthy mate, no aid of son-in-law, no assistance of note from her three sons,” in the words of a 1957 article by historian Jan Bowan. She broke with the established patriarchy of Mexico and Spain to live on her own terms as the head of a family governed by its women, a feminist pioneer ahead of her time.

The Briones adobe at El Polin Springs today is completely buried. But Voss’s excavations there have revealed evidence of a pluralist household, where the sisters not only blended their African heritage with the Mexican Indian heritage of their husbands but also adopted at least one Ohlone orphan and incorporated other adult Ohlone into their extended family through baptismal sponsorship, intermarriage, and long-term labor- and land-sharing relationships. Another finding of interest was the degree to which the Miramontes and Briones families shaped this environment. “We’re learning that the landscape of El Polin Springs was modified more than we would have deduced from documents in the historic record,” says Voss. “The water impoundment, the cuts into the hillside—we did not expect to see these things, and they give us a better picture of how people were relating to the landscape at that time.” Many recovered artifacts remain under study for further conclusions, which Voss hopes to include in a book forthcoming in 2008.

Restoration Versus Design

“Restoration” of a landscape often implies a return to a previously pure state, while “design” connotes moving forward to a new, planned manifestation. Both meanings overlap in the Tennessee Hollow watershed, where the Presidio Trust— the federal agency that runs the park in partnership with the National Park Service—has embarked on a number of ambitious remediation projects to clean up army pollution while bringing back pieces of San Francisco’s dearly departed native landscapes.

- A team led by Stanford archaeologist Barbara Voss conducts a dig at the Briones home site. Photo courtesy Stanford University-Tennessee Hollow Watershed Archaeology Project.

The vision includes removing culverts and landfill to sculpt a trio of seasonal creeks, from El Polin and other nearby springs, joining into a single open waterway that will flow to the Crissy Field marsh. One of the lowest segments of this stream, north of Lincoln Boulevard between Halleck and Girard at an area called Thompson Reach, has already been daylighted—80,000 tons of fill and a 72-inch drainpipe were removed in 2005 and replaced with a winding creek bed, its sandy banks replanted in 2006 and 2007 with over 100 species of native plants grown from propagules collected inside the park.

Trust ecologist Mark Frey notes that the stickleback, a highly adaptive fish living in both salt- and freshwater environments, has already migrated upstream from the Crissy Field marsh into the redesigned creek.

“This restoration is a great opportunity for public awareness and education about one of San Francisco’s best remaining natural areas and its important role in the history of the city,” says Allison Stone, senior environmental planner for the trust. “Our restoration of Tennessee Hollow speaks to deep and essential relationships between the water, the earth, and the people, plants, and wildlife that depend on them.”

But the project also brings controversy. The most difficult issue involves the Morton soccer field on the eastern fork of the watershed, which needs to be relocated to make way for a restored creek. The prospect of losing the field brought out the public in droves to a meeting last fall, creating fear that the whole project could hinge on finding another pitch for the soccer players.

The Presidio Environmental Council, which includes representatives of several local environmental groups, sent a letter in late 2006 pushing for a “maximum possible restoration option” in a forthcoming revised plan for the watershed. That would mean removing all army dump sites and nonhistoric structures to make way for restored riparian and upland habitats.

Meanwhile, as many as five landfills in the watershed still need remediation, including the toxic mysteries of Fill Site 1 and Landfill 2 in the headwaters of El Polin. Those two sites are scheduled for removal in the summer of 2010.

The Power of Allegory

History is written by the victors, and the cultural identities of people and places are defined by the stories we tell about them. Tales from the Tennessee Hollow watershed, and from El Polin Springs in particular, could fill many volumes. From the time when the Spanish first founded the Presidio and bundled the Indians off to the missions, those stories have tended to minimize the Ohlone’s long and symbiotic relationship with the landscape. But shellmounds and ancient human burials discovered at Crissy Field speak to the legitimacy of the Ohlone claim as the first human inhabitants here.

El Polin’s often-contradictory chronicles do reveal a common thread: the mythic and magical qualities we assign to water. Every human culture has used water in religious ritual, often marking a passage from the profane to the sacred—a transformative quality that elevates water from element to allegory. Little wonder that a splash of water on the forehead can turn a heathen into a Christian, or that a small freshwater spring on the farthest frontier of the Spanish empire could rise to such stature as laudable multiplier of the garrisons.

It remains to be seen if water in a seasonal creek can restore the landscape of the Presidio to a semblance of itself as it was in the times of the Ohlone and early Spanish settlers. But whatever shape this land assumes, one hopes that the architects of its redesign will hear the tales that El Polin has to tell. Those old stories can let the dead sit up and talk like unknown, remembered channels linking the past to the future. Such deep connections form the true substance of our collective legacy.

.jpg)

-300x196.jpg)

.jpg)

-300x186.jpg)