Text and research by the California Center for Natural History

2020 Spotlight Species

California ground squirrels (Otospermophilus beecheyi) are integral to the diversity of birds and plants in Bay Area grasslands, like those growing in Sunol Regional Wilderness and Brushy Peak Regional Preserve. Squirrel burrowing breaks up an otherwise uniform landscape, creating areas with more bare ground, shorter vegetation, and more grass; this affects the diversity of animals living near squirrel colonies. Such habitat islands have more centipedes and ground beetles, for example, which may attract insect-loving grassland birds like the threatened burrowing owl. These species, along with the squirrels, become the prey of larger predators. Unlike many burrowing squirrels, some California ground squirrels stay aboveground for much of the winter, becoming an important meal for raptors like the ferruginous hawks overwintering in the Bay Area.

An Ancient Arrival

Every fall the ancient bird species known as the sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis) arrives in the Delta and Central Valley and stays through winter, eating in fields, grasslands, and open spaces. You can see the juveniles—they lack the red crown and white cheeks of adults—through the winter hanging around with their parents, who usually mate for life. At night the cranes roost in wetlands, often in huge flocks. The best times to view these famously stunning congregations in all their flapping, leggy glory are sunrise and sunset. View the cranes at Woodbridge Ecological Preserve and the Cosumnes River Preserve.

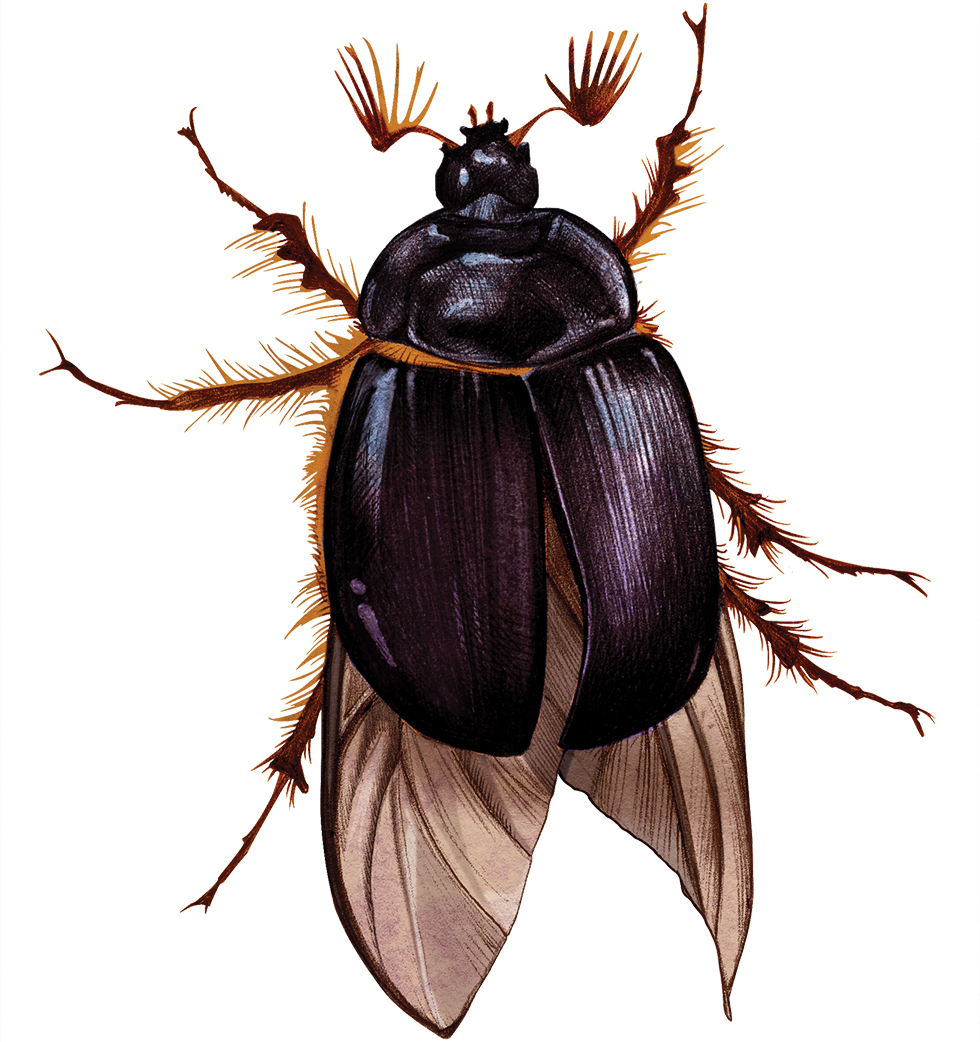

Beetle Mania

As unusual as it is for insects to fly in the rain, adult rain beetles (Pleocoma spp.) are known for it. They emerge from soaked ground in search of mates, their purpose-driven peregrinations reflected in their anatomy: they have no mouthparts or digestive organs and survive on body fat built up during their eight- to 13-year subterranean larval stage. Once males emerge, they have a handful of days and just enough energy to fly a few hours, as they search for flightless females, who emit pheromones and wait for them at the openings of underground burrows.

Calypso the Deceiver

You’ll know you’ve spotted an inexperienced bumblebee when it settles on the lip of a fairy slipper orchid (Calypso bulbosa) for a meal. This single-flowered perennial usually blooms here by March, and if you were a bee you’d probably be lured by its purple petals too. But soon most bees learn the fairy slipper is, like a lot of orchids, a “pollinator deceiver.” Duped by the flower’s sweet smell and yellow hairs, the bee inadvertently picks up the flower’s pollen sac while looking for nectar…but there is none. Even though the reproductive odds seem against C. bulbosa, it grows in undisturbed northern forests around the world, the only species in the genus. Look for our western variety, C. b. var. occidentalis, in redwood and Douglas fir forests.

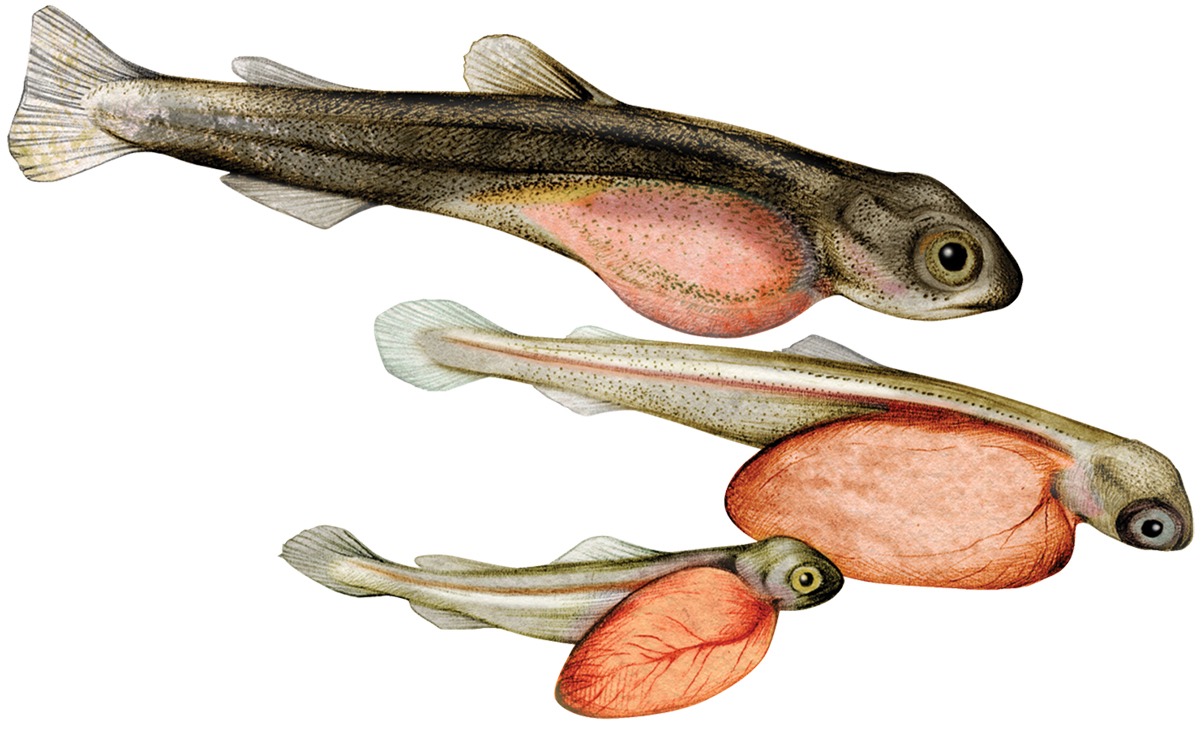

From Winter to Spring

After coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) return to their birthplace by early winter and spawn, it’s only a matter of weeks before they succumb to exhaustion from their journey and drift downstream. Scientists have traced what happens to the salmon carcasses—they literally infuse the surroundings as nutrients. Nitrogen isotopes that occur in ocean salmon are found nearly everywhere in the stream—the trees and vegetation growing along the banks, other fish, microbes covering rocks, and local insect populations. Once salmon eggs hatch, the tiny alevin live amid the gravel, taking sustenance from their attached yolk sac before entering the open stream, now fertilized by their parents.

One World

The giant skyborne rivers of water traveling from the tropics to the West Coast during the winter and spring account for about 30 to 50 percent of California’s rain. These atmospheric rivers need particles—seeds of ice, dust, pollution—to help pull the water into droplets that fall as rain, and a 2019 study finds that dust from China’s northwestern Taklamakan Desert reaches Northern California about 500 times a year. The big question researchers are asking: Does China’s dust seed our rainfall?