On the edge of the tidal marsh fringing Suisun Slough, a streaky dark-brown sparrow gleans seeds of tules and other rushes from the exposed mud. A shadow passes: a northern harrier, cruising for mice. The sparrow vanishes into a tangle of winter-brown stems. The bird is a Suisun song sparrow, and its presence is part of what makes the Rush Ranch Open Space Reserve a biodiversity hotspot. Biodiversity often evokes images of exotic rainforests and coral reefs. But there are places close to home that hold a surprisingly rich sample of life’s variety. Rush Ranch, south of Fairfield in Solano County, protects one of the few remnants of estuarine marsh in the Bay Area and shelters at least a dozen plant and animal species that are either officially rare or endangered, or have been proposed for listing.

Cupped between Suisun Bay to the south and the gently rolling Potrero Hills to the north, Rush Ranch’s 2070-acre mosaic includes both pasture and native grassland. But the marsh is the heart of the place. Located near the mouth of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, Suisun Marsh was once the largest estuarine marsh in the continental United States. Now most of it is seasonal brackish wetland (often dry in summer), managed as waterfowl habitat, and only 10 square miles is left in its original tidal state. A tenth of that lies within the Rush Ranch preserve.

Tidal marsh, defined by the confluence of fresh and salt water and the influence of rising and falling tides, exemplifies the richness of ecotones, or edge environments where two natural systems meet. It’s a prodigiously productive habitat. Plant detritus feeds small invertebrates, which feed fish, which in turn feed herons, cormorants, and river otters. The sloughs that thread Suisun Marsh serve as nurseries for delta smelt and other fish. Before European colonization, its bounty sustained the Patwin people, whose seasonal villages bordered the marsh. Today at Rush Ranch you can see a grinding rock (a flat sandstone outcrop pocked with mortar holes) where Patwin women processed dried meat, salmon and sturgeon, mussels, and seeds.

Inhabitants of the marsh have adapted to its brackish water and tidal changes; some are endemics, found nowhere else. The marshes of Suisun Bay are home to the entire population (estimated at 58,800) of the Suisun song sparrow, a sedentary subspecies that never strays far from its small patch of tules and bulrushes. The song sparrow is a protean species, varying in size, plumage, and habitat preference ranging from the Aleutians to the highlands of central Mexico. Of the 30-odd subspecies, the Suisun song sparrow has the darkest coloration, the widest bill, and lives in uncommonly high densities, up to four pairs per acre. Because their kidneys concentrate and flush the chloride component of salt, they can drink the marsh’s brackish water. This subset of song sparrow genes reflects the fresh- salt balance of a healthy tidal marsh. Ornithologist Nadav Nur, who is studying the subspecies for the Point Reyes Bird Observatory, says the population appears stable for now, although many nestlings are lost to predators. However, any major change in Suisun Bay’s salinity could put the birds at serious risk.

- Suisun thisle, a Suisun marsh endemic. Photo by Brenda Grewell

The purple-flowered Suisun thistle is another marsh endemic. Similar to the exotic and more prevalent bull thistle, it is distinguished by its hairless leaves. Rush Ranch may have the last surviving stand of this endangered plant, which is threatened by competition with another exotic, perennial peppergrass. The Suisun aster and other rare plant species share the thistle’s habitat; all of these must be able to withstand the high salinity levels that come from periodic tidal inundation of their slough-side location.

Another endemic, the Suisun ornate shrew, is rarely seen- even by biologists. This four-inch-long predator lives fast and dies young, stoking its metabolic fires with up to three times its weight in insects and crustaceans daily. In winter, when food is scarce, the shrew shrinks, reducing its body mass by one-third to one-half. The shrew is an annual mammal; most die early in their second year, soon after breeding.

The Marsh Trail at Rush Ranch is the best point of entry to the world of the song sparrow and other marsh dwellers. An easy 2.2-mile loop that is open year-round, the trail runs from the old ranch buildings to a low hill overlooking Suisun Slough, which is a good place to sit and watch the boat and bird traffic. Below the hill the trail transects a corner of the tidal marsh, with a side path where some marsh plants, including several confusingly-similar members of the rush family, have been labeled. (The ranch is named for the pioneer Rush family, not the plants.) Even on weekends you may have the trail all to yourself, your tranquility disturbed only by the occasional jet from nearby Travis Air Force Base.

The marsh yields its secrets slowly. It’s easy enough to spot the sparrow (it will pop into view along the edge of the trail, delivering its musical trill from a tule or cattail perch in spring and summer). Other inhabitants- salt marsh common yellowthroats, marsh wrens- are more difficult to spot, though you’ll probably hear them. With luck, you may hear the staccato call of the rare California clapper rail; a small population of this endangered marsh bird here appears safe, so far, from the red fox predation that has devastated them elsewhere. An American bittern may flap heavily out of the marsh or freeze in place, bill skyward, trying to escape detection. Although river otters are more active at night, there’s visible evidence of their presence: otter slides where plants are bashed down, grass tufts used for scent-marking, and piles of dung-spraints- studded with bits of crayfish shell.

- Several years ago, the brackish diked wetland along Marsh Trail wasdredged for levee repair. The following spring, it was carpeted withbrass buttons (Cotula coronopifolia). The marsh is now mostly filled in with sedges and cattails. Photo by Terry Chappell

The Marsh Trail also leads you to another ecotone: the boundary between marsh and upland. Here, native purple needlegrass persists among imported forage grasses. Shrubby vegetation at the marsh’s edge shelters sparrow-sized California black rails, salt marsh harvest mice, and shrews when high tides flood their homes in the pickleweed. Burrowing owls find housing and food on grassy slopes, and golden eagles cruise for larger prey. Red-tailed hawks, northern harriers, white-tailed kites, and American kestrels are year-round residents. Winter visitors from the north include short-eared owls, ferruginous and rough-legged hawks, merlins, and the occasional peregrine falcon (Katit, the creator spirit of the Patwin).

Harriers- long-winged, low-flying hawks with a distinctive white rump patch- perform their spectacular courtship flights here in early spring, while wildflowers blanket the hills. The endangered Contra Costa goldfield, a sunflower relative, blooms in March and April in seasonal wetlands along Spring Branch Creek, which intersects the South Pasture Trail. Later as the grasses brown, the marsh vegetation turns green. Come midsummer, the Suisun thistle and Suisun aster bloom, western kingbirds and loggerhead shrikes bicker along the pasture fences, and alkali bees build their volcano-shaped nests near a spring-fed alkaline pond along the Marsh Trail. Fall brings southbound shorebirds to the reserve’s wetlands; at least 14 species remain as winter residents. Barn owl encounters are possible at any time of year; these spectral birds have moved into the 19th-century barn, the stable, and even the tractor shed. Unfortunately, they have added clapper rails to their diet.

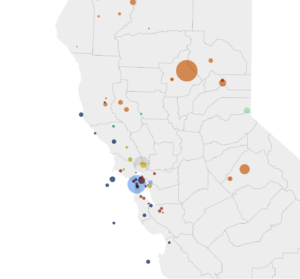

- Map by Benjamin Pease

All in all, with its surprising biodiversity, mix of upland and marsh habitats, human history, and secluded setting so close to the I-80 corridor, Rush Ranch is a significant- if still little known- addition to the Bay Area’s public lands. It’s currently a candidate for National Estuarine Research Reserve status; joining other such areas managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration would bring new resources for restoration and education to the reserve. Rush Ranch was purchased by the Solano County Farmlands and Open Space Foundation in 1988 with a grant from the Coastal Conservancy and seems to be a personal favorite of Foundation staffers and volunteers. “It’s a real jewel,” says Land Steward Ken Poerner, “A place to enjoy the solitude.”

Getting There: From I-80 northbound, take the Rio Vista exit onto State Highway 12. Turn right onto Grizzly Island Road and proceed two miles to the Ranch. The reserve is open daily, 8 am to 6 pm. A small visitor center displays Patwin artifacts, ranch history, and flora and fauna, and dispenses leaflets for the Marsh and South Pasture trails. The Suisun Hill Trail begins on the other side of Grizzly Island Road. The Rush Ranch Education Council has an active docent program; for information call (707) 432-0150, or visit their website (www.rushranch.org). They also publish the Rush Ranch Handbook ($5), which contains plant, bird, and butterfly lists and illustrations, as well as a useful introduction to the human and natural history of the ranch.

.jpg)