Porcelain crabs are adaptive critters. As they scuttle around the intertidal zone, they have to withstand wide swings in daily temperature and ocean water acidity.

But even a hearty porcelain crab may be susceptible to the extremes brought on by climate change. Researchers at San Francisco State University’s Romberg Tiburon Center have just published a paper showing that these ubiquitous crabs, which inhabit nearly all the world’s oceans including Northern California coastal waters, can run out of energy for much beyond survival when their environment becomes too warm and too acidic, even for a brief period of time.

The study, published last week in the Journal of Experimental Biology, has been billed as the first of its kind to measure the combined effects of spikes in higher temperatures and higher water acidity on an intertidal zone organism. The conditions were meant to mimic the future ecological conditions this species may face under climate change.

“We know these animals are adapted to really extreme environments, and one of the things we’ve learned from crabs is that with respect to temperature, they are already living close to what they can tolerate, so they don’t have much of a safety margin,” said Jonathan Stillman, a biologist at the Romberg Tiburon Center, whose lab conducted the study.

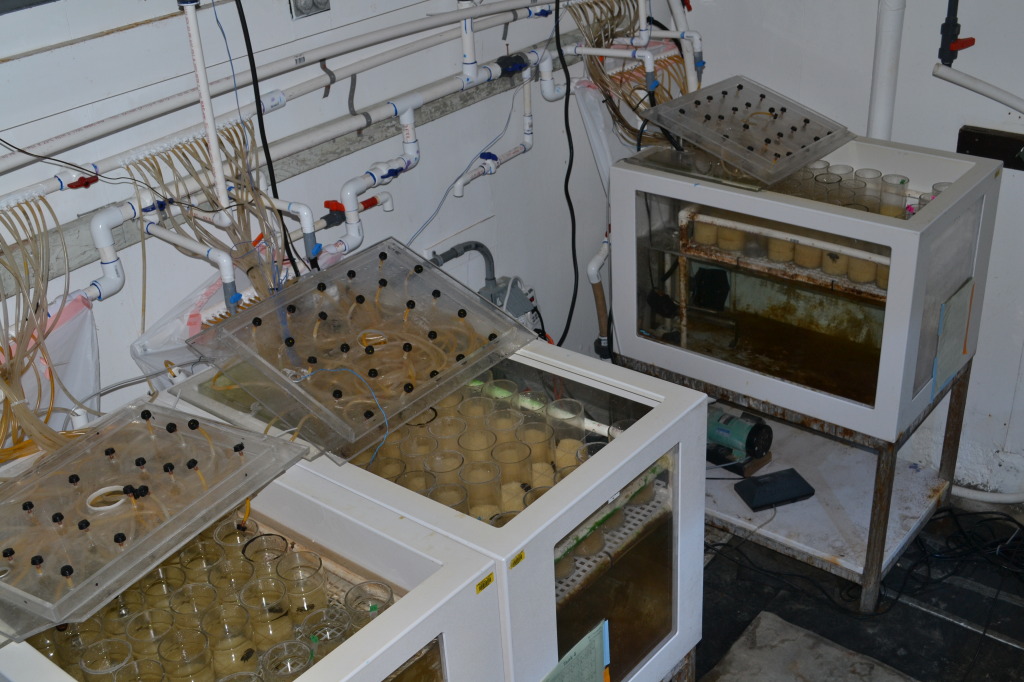

To do the experiments, Stillman and his colleagues built a special aquarium at the Romberg Tiburon Center that allowed them to simulate the seashore environment, including tidal changes. They collected porcelain crabs from Fort Ross and put them in the tanks. Then they simulated a low tide during the daytime, exposing the crabs to variations in air temperature to replicate the day-to-day changes a crab would typically face on a cloudy or sunny day.

They also simulated a nighttime high tide with the crabs submerged in water and exposed to varying levels of acidity. Crabs often experience natural fluctuations in water acidity as photosynthesizing aquatic plants slow down the absorption of carbon dioxide during low light conditions.

Then the researchers dialed up the extremes. Some crabs got low-tide temperature spikes of as high as 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) that was meant, at an extreme, to simulate a heat wave of the future. Some also got extreme dips in water pH from a baseline of pH 8.1 to as low as pH 7.15 (a level that’s seen in some parts of the world and could happen on the California coast as well under ocean acidification).

The crabs were individually placed in vials while a respirometer measured oxygen consumption rate, a standard way of estimating the metabolic rate.

An interesting thing happened. Extreme water acidity alone had no bearing on the crabs’ respiration rates, perhaps given the natural ability of crustaceans to internally regulate pH in their hemolymph (the equivalent of blood for invertebrates) and by way of leg membranes that aid in pH regulation and passive respiration. As expected, extreme air temperatures bumped down respiration, in this case by 17 percent.

But the combined effects of extreme acidity and extreme temperature reduced respiration rates by 25 percent — a notable hit for the species.

The paper speculates that while intertidal organisms may be able to withstand the effects of climate change, there would be some negative effects on performance.

“The take home result is that in the future their overall energy budget is going to get smaller,” Stillman said. “They had a lower metabolism after being exposed to big extremes in temperature and CO2 and they were spending more of that energy on just staying alive.”

Stillman said the impacts might be seen at the cellular level, whereby the cellular machinery begins to falter. Or it could be more of a physiological reaction, in which an organism slows its response to its environment in order to acclimate to the stress. He compared the crabs to long-distance runners.

“If a person is a runner under benign conditions — a flat road — they run as fast as they can. There’s no reason to vary their running speed, so they are going at a high rate,” Stillman said. “At some point they start to encounter a lot of hills and need more energy to get up or down, so they might slow down in the flat areas so they have energy to spare when they hit the hills.”

He added:

“Under conditions when the environment is more variable, they slow down the basic speed so they have the capacity to respond to extreme environmental periods.”

What happens under climate change when extremes in water acidity and temperature become more frequent? Will the porcelain crabs, and other intertidal species, be able to adapt?

Porcelain crabs are extremely diverse, and species within the group are suited to many different local conditions with varying temperatures and pH. You could say they’ve been adapting well for a very long time. But the pace of climate change may be too much for them.

“The rate of adaptation is probably orders of magnitude slower than the rate of environmental change in the world because of the burning of fossil fuels,” said Stillman.

He noted that marine invertebrates tend to have large populations spread out over wide areas, making it more difficult for natural selection to act quickly on a species. A follow up set of studies out of his lab will measure the impacts of high heat and acidity on growth, reproduction and behavior — all aspects of the ecological performance of the crabs.

“Something has to give. They don’t have infinite amounts of energy to do all that stuff, so there have to be some tradeoffs,” Stillman said.