By all accounts, the 2007 Lick Fire was a firestorm, with towers of flame and plumes of smoke thousands of feet tall. In the end, it consumed 47,000 acres, most of it in Henry W. Coe State Park, east of Gilroy. Just days after the fire, Coe Park’s volunteers were on the scene. Biochemist (and long-time Coe volunteer) Winslow Briggs, retired from the Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford, organized a team to monitor the dramatic changes and subsequent recovery of the landscape. Two years later the “fire followers” of Coe Park are still at it, and even in the face of park budget cuts, they hope to keep their research going for years to come.

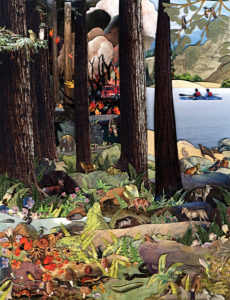

Coe’s large size (at 87,000 acres, it’s the largest state park in Northern California) and rugged topography give it wide gradients of altitude, temperature, and moisture that in turn nurture diverse ecosystems–from chaparral to oak woodlands to riparian corridors to ponderosa pine forest. Twenty volunteers are tracking changes at 30 different sites across the park to see how a single fire has affected many different habitats.

Each site contains five half-meter plots pinpointed with GPS coordinates. The purpose of these sites, says Briggs, is to “try to record everything coming in,” from long-dormant seeds to opportunistic invasives. Volunteers have already found a few plants that had not been seen here in decades. Apparently, their seeds had been lying dormant for almost 50 years, since the last major fire in 1961.

- White mariposa lilies bloom in one of the marked plots volunteers are using to study post-fire regrowth. Photo by Winslow Briggs.

Volunteers visit their sites about every six weeks to record species, numbers, and the state of the plots with photos and GPS information. Another volunteer has even tapped into NASA satellite photos to track changes in photosynthesis data recorded in Landsat imagery.

Besides these 30 sites, Briggs has also set up another 32 plots where he and his wife, Ann, keep tabs on a half dozen species of bulb plants and record their post-fire behavior. One of the biggest surprises, says Briggs, is the profusion of flowering bulb plants after the fire. “Mariposa lilies, globe lilies, and star lilies would flower occasionally before the fire, but they exploded afterward,” says Briggs. “It was just an astonishing display. I had a 1.5 meter by 1.5 meter plot with something like 30 mariposa lilies, but the ground around them was bare.”

Briggs, ever the biochemist, just received park staff approval for a more advanced study on these sites to examine the role of a recently isolated chemical compound in smoke that may trigger some species’ seed germination. A focused look at the role of smoke in regeneration could produce new data that would be valuable for future ecological restoration efforts. But Briggs is characteristically modest: “Even if the data from the study never gets published, at least we’ll have a group of volunteers who know a lot about natural history.”

The volunteer researchers are part of the Pine Ridge Association, and Briggs’s fire-follower study is just a small slice of what they do. The association has about 400 members, about a quarter of whom become uniformed volunteers at the park. These volunteers, among the most active in the state, support the handful of employees who manage the park. The group puts in 20,000 hours of work annually, equal to 10 full-time employees.

Participation in the study requires a huge commitment of time and energy, but Briggs says it was easy to recruit his research team. “They just jumped on it,” he says. “There’s a certain prestige to it–we have to have uniforms and special four-wheel-drive training. Some of these sites are 11 or 12 miles from the nearest trailhead, so it gets people into the backcountry where many of them wouldn’t be able to go otherwise.”

But all of this–including the fire-follower study–may come to a screeching halt if the park is shuttered due to the state’s budget crisis. When I ask Briggs, who has been volunteering at Coe for more than 30 years, about the threat of the park’s closure, the curious scientist prevails: He says his study, and the hundreds of hours logged in data collection, will really be useful only if he and his volunteers can keep at it for another five years. Or more.

Learn more about the fire research at coefire2007.info and more about the park at pineridgeassociation.org.

.jpg)