The California Current ecosystem in the ocean off our coast is a dynamic place with distinct seasons, one of which usually peaks near the autumnal equinox. The northerly winds relax then, and the water and air temperatures warm. This is the time for humpback and blue whales to arrive near our shores to feast on a massive abundance of krill.

Another phenomenon, equally fabulous but much lower in the food chain, can also occur in the ocean at this time of year: bioluminescence, or “living light.” A veritable light show may manifest in the water as early as June, becoming more frequent by September. In some years, displays begin as early as April and may continue well into November or beyond.

Among humans, an urge to understand bioluminescence generally follows close upon a first encounter with it. Perhaps you are sitting on a dune or bluff at night, far from city lights, entrained by the breaking waves; when darkness finally inks the sky, the surf takes on a greenish white glow or even a roiling, bright pearlescence. Or, your beach walk has gone longer than planned, and a dense cloud cover soaks up the last ambient light; then your footfall in the wet sand generates bursts of ethereal sparkle, sometimes lasting seconds and flashing many inches outward. Kicking and splashing and general merriment may ensue.

Boaters sometimes encounter the phenomenon in the ocean, lighting up their vessel’s wake or streaming off the backs of dolphins that ride the bow wave. Nocturnal kayakers in coastal estuaries find explosions of light as they glide through the water. Here the primary consideration is safety: Fog banks that coincide with dark night skies (when the “living light” shows up best) can obscure the route back to shore. But those who take the proper precautions bring back seductive tales of their encounters: of drifting above eelgrass beds illuminated by the splashing of the paddles; of bat rays winging their way through the shallows, resembling starships traversing a twinkly galaxy; and of the sleek forms of harbor seals passing by underwater, glowing. Any motion in the water will light things up when bioluminescence is “on.”

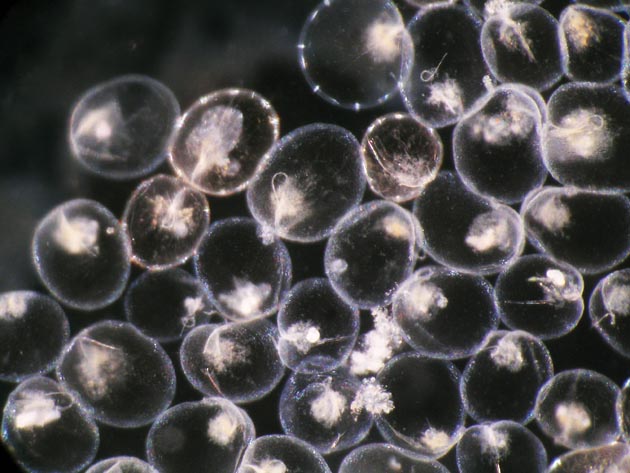

The “bio” behind this particular luminosity consists of a marine microorganism, a single-celled creature that is a kind of dinoflagellate. Along with much other life in the fertile California Current, these tiny organisms explode into profusion during the long days of May, June, and July. Seasonal upwelling then brings nutrients up close to the surface, propelling the biodiversity of these waters. Though present year-round, the dinoflagellates multiply in earnest near the summer solstice and reach their greatest abundance in September and October. Then they can concentrate in dense clouds in surface waters and shallow shoreline basins. That’s when human “biolume” aficionados head for accessible bays and beaches on dark nights.

As a group, dinoflagellates have varied arrangements vis-à-vis the food web. Some can photosynthesize, like plants. Some capture and ingest other creatures, like animals. Some go both ways. All of them get their name from a pair of threadlike whips, wrapped around their tiny midsections, which they may flail to slightly control their drifting positions in the water column.

Our local bioluminescent dinoflagellate has both a scientific and a common name that are poetically right on. Typically dubbed Noctiluca for its genus, it has the species name scintillans, giving us the Latin (roughly) for “glistening night light.” And the little creature’s best known common name is, appropriately, sea sparkle.

Noctiluca’s glowability most likely has to do with defense. Everything in the food web needs certain equipment not only to find prey but also to avoid becoming prey. Suppose that Noctilucas are floating around en masse, encountering beings even smaller than themselves, to eat. The approach of a larger creature, potentially the enemy, is quickly revealed, as its movement jiggles the water and thus the dinoflagellates’ cell membranes. They suddenly, collectively, light up, exposing the intruder’s location and even its size and shape. Chances then improve for the next predator up the food chain to pounce. In this big-fish-eats-little-fish-eats-tiny-prey-eats-dinoflagellate scenario, a flash of light can interrupt the sequence right before “tiny-prey-eats-dinoflagellate,” to Noctiluca’s advantage.

The purposes that life forms have for emitting light, especially in the ocean, are so basic that the trait is common there. On land it is much rarer: the best-known terrestrial group to bioluminesce are the beetles called fireflies (and their larvae, called glowworms). In the marine environment, however, some 90 percent of residents—jellies, squid, fishes—can glow or flash or somehow signal using living light. Since the vast majority of them live in total darkness, in water far deeper than sunlight can penetrate, bioluminescence is equivalent to sight (for creatures with optic nerves).

By now you must be wondering just how sea sparkle works (while scheming how to get some on your very own toes).

Essentially, two compounds stored in a body—be it multi- or single-celled—mix together in the presence of oxygen, and voilà—a cold bright strobe of visible light is produced. The two ingredients involved are a light-emitting compound called luciferin and an enzyme called luciferase that serves as the catalyst. Both of their names derive from the Latin lucifer, meaning “light-bearing.” (A more famous entity with that name was a certain high-ranking angel who fell from grace but retained the name synonymous with his erstwhile luminosity.) There are several types of luciferin, and the dinoflagellates have their very own (distinct from the luciferin in fireflies or deep-sea fish), which is a chemical derivative of chlorophyll.

Bioluminescence happens when the catalyst luciferase ignites the luciferin, like a match put to kindling. The light-emitting reaction that results is a cold one, unlike the incandescence of a burning candle or electrical bulb. Because heat is not a byproduct of bioluminescence, the light produced is essentially 100 percent energy-efficient.

The mechanics of all this have understandably commanded people’s interest for millennia. The explanation for “living light” eluded scientists until 1887, when Raphael DuBois found a fairly simple way to separate luciferin and luciferase (which he so named) derived from a Caribbean cricket. In a famous demonstration at the Paris International Exhibition of 1900, DuBois filled sconces in a dark room with bioluminescing stuff and produced enough light for people to read Le Monde (or the like).

Since then, people have explored applications for bioluminescence, from miners’ lamps to nocturnal naval advantages (recall Noctiluca’s strategy when it lights up an enemy). The scientific effort to purify and thus analyze luciferin found in a glowing jelly in the Pacific Northwest ultimately earned the Japanese biochemist Osamu Shimamura a Nobel Prize and precipitated a revolution in the science of molecular biology.

Which may be a long way to travel, in our mind’s eye, from the sand beaches of north-central California. Yet the general fascination with bioluminescence is a proper backdrop for one’s own local quest for contact with sea sparkle; for ventures to the cold water of our home place in the sea-season of summer through early fall; at night, when the moon is small or has set, far enough from city lights, perhaps under a good dense fog layer. It’s then that we may cavort in wet sand at the sea’s edge, seeking to excite the “sea sparkle.” Perhaps the shore will be limned with rapid jets of light expressing the pure energy of sea waves. The brilliant water will beckon, the surf all a-tumble with chaotic glow. If conditions are known to be safe (check for undertow; bring a friend), this may be the moment for the skinny-dip of a lifetime.