A restored tidal marsh might be described as a primal mud pie, rich and fertile enough to sprout a meringue of fresh toppings. An array of native critters is then lured to the meal, where they proceed to feed, nest, roost, and breed as in ages past. The shoreline of San Francisco Bay’s northernmost lobe—called San Pablo Bay—has begun to dish out an ample buffet of such sites.

The result is a swath of refreshed habitat that forms a major way station for waterfowl on the Pacific Flyway in the near term and will provide the Bay Area with one of its last, best chances for helping wildlife adapt to climate change and sea level rise over the long term.

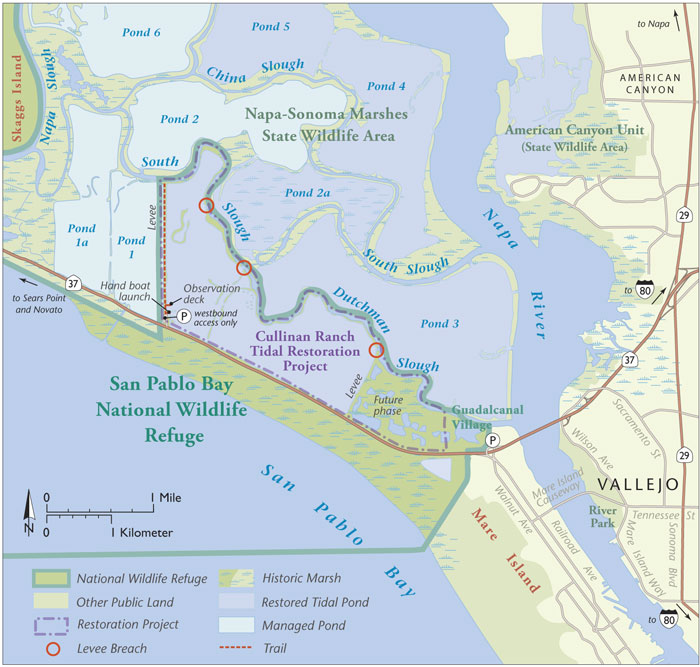

Cullinan Ranch, recently opened for public visitation as part of the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge, is a crucial link in the midst of this lush, gold-green arc of pickleweed, cordgrass, brush, and brackish water stretching from the broad estuary of the Petaluma River to the Napa River’s eastern bank.

On a bright, clear Saturday morning in late September, three people drove out to Cullinan to savor the result of a decades-long effort to escort nature back onto tidelands where it had once reigned supreme. “Soon, this whole region will be a birding mecca,” predicted Megan Elrod, a field biologist with Point Blue Conservation Science, one of the groups that advised the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) on the Cullinan restoration. “This site is already on people’s radar. We just need the plants to take hold, the sloughs to form, and more public access points like this one.”

We prepared to launch a craft from Cullinan’s small-boat dock, a prominent feature of a new visitors’ facility that also includes a fishing deck, parking lot, and 1.4-mile-long hiking and biking route along a levee-top road. Megan and I planned to paddle out into Cullinan’s 1,200 recently sculpted and flooded acres, while Mark Dettling, an avian ecologist who also happens to be Megan’s husband, planned to drive and hike along other levee trails nearby to score his own observations with a spotting scope.

A visitor can explore this broad 14-mile-long crescent of tidal, brackish, and freshwater marshes around the northern shoreline of San Pablo Bay by either land or water. However, Cullinan—as a large tidal pond linked to sinewy sloughs—makes kayaking or canoeing a particularly inviting way to undertake your exploration.

Because it’s now linked to the Bay, water here perpetually rises or falls with the tides, which means one must take those yo-yoing water levels into account when planning an outing. Within Cullinan itself, you’re generally better off launching on a flood tide (when the water is rising) than on an ebb. That way, should you happen to get stuck in a shallow or on a mud bank, all you need do is wait a bit before you can float off.

If you happen to feel more adventurous and are able to burn a full day, you could launch at peak high tide, ride the ebb out of Cullinan and into the larger sloughs that snake through the surrounding Napa-Sonoma Marsh complex, wait out the slack tide in some pleasant location, then ride a flood back.

I’d tried that a week earlier, finding my way out of Cullinan via one of the intentional levee breaches that were used to flood its sprawling pond last January. I rode the ebb out into Dutchman Slough, which writhes along the northern levees of Cullinan, and down to the broad lower reach of the Napa River estuary, then south to the launch ramp in Vallejo, where I hauled out, ate lunch, and did some reading. After the tide turned, I reversed my course to achieve a round trip of about 16 miles in some seven hours, including wait time for the tidal shift.

Besides many fine close-ups of San Pablo Bay’s resident birds which Elrod dubs, “the usual suspects”—least sandpipers, great blue herons, great egrets, and assorted ducks, gulls, wrens, and sparrows—on that outing I scored unusual sightings of a mated pair of mute swans and a glimpse of an errant Steller sea lion bull who startled me by making a loud snort as he surfaced right beside my kayak in Dutchman Slough.

For the briefer outing with Elrod, I selected from my modest fleet of watercraft a two-seat, hand-built, cedar-strip canoe, which Dettling helped me tote over to Cullinan’s new small-boat launch dock. “It’s the first time I’ve used this dock!” Elrod exclaimed. “It was installed well before they breached the levee and flooded the ranch. For months I saw it out here just sitting down on the dirt.”

Now the dock peaceably bobbed on the recently filled thousand-acre pool of beige water. We launched, and a few paddle strokes brought us abreast of a tiny island, where a roosting great egret eyed us dubiously.

“Those little islands are called ‘high-tide refugia,’” Elrod told me. “We’re starting to see them being built in restoration sites all around the Bay. Refugia can jump-start colonization by marsh plants. As vegetation grows on them, song sparrows and common yellowthroats move in, then black-necked stilts and American avocets, and eventually black rails—which will be exciting.” The egret apparently felt so secure on his little island refuge that he didn’t even bother to take wing as we drifted by.

With every paddle stroke, it felt as though we were gliding further back in time. Road noise receded behind us while wide marsh vistas unfurled before us. There’s something about wide-open spaces dotted with wildlife that’s soothing to the soul. We were only a few miles away from the city of Vallejo, yet the distance felt far greater. We might’ve glimpsed only remnants of the vast storms of airborne waterfowl reported by pioneer George C. Yount on his trek through this region in the 1830s, but it seems clear that those remnants can now increase, making this place a tranquil refuge for humans as much as for wildlife.

When astronauts in science fiction hope to colonize a planet, they tend to begin with a process called “terra-forming”—applying measures to encourage biologic life as we know it to root on alien soil. When scientists on Earth try to restore wildlife habitat, they engage in a similar process. But in the case of tidal marshes, gaining skill at it has been a learning process. The first attempt at restoration along the shore of San Pablo Bay—the 300 acres of the Sonoma Baylands (southwest of Sears Point)—encountered challenges establishing the tidal flows needed to form natural sloughs and receiving the sediments necessary for native marsh vegetation to take hold.

So at Cullinan Ranch, Ducks Unlimited—one of ten outfits cooperating with USFWS on the restoration—was asked to help with the design. Russ Lowgren, an engineer with DU, has eight years’ experience crafting habitat restoration in California. A big part of his job at Cullinan was protecting Highway 37, which forms the unit’s southern boundary, from the impact of erosive forces. This was achieved by burying blocks of “geofoam” (expanded polystyrene) at the proper angle to dissipate wind and wave energy along the edge of the roadway. These blocks were sealed in a special membrane to reduce potential decay from fuel spills or oil leaks.

Another key concern was exactly how much tide influx to permit. The right amount would allow the waters to drop sediment and build up natural mud banks and sloughs; too much would scour these structures and stymie the growth of native vegetation. “I decided the solution was to connect this bathtub with a straw,” Lowgren told me.

This decision means the thousand acres of water constituting the main Cullinan pond are filled and drained through just three levee breaches. For the paddler, this means two things. Currents inside the pond are negligible, so if the tide is high enough to float your boat, you’re pretty much good to go. However, currents at the breaches can grow potent, on the order of a Class II whitewater rapid. So if you plan to navigate through them, “going with the flow” is a rather important principle.

On this occasion, though, Elrod and I never even neared a breach channel. We simply stroked a mile-and-a-half north and admired least sandpipers, double-crested cormorants, and a huge raft of white pelicans. Then we swung around and faced a light breeze on our way back to the dock. Wind, by the way, should also be taken into account in this broad, flat, and open area. I’d advise paddling here only when wind speeds are predicted to be 15 mph or lower…unless arm-wrestling Aeolus happens to be your thing.

But if strong winds don’t threaten and you wish to travel more miles than we did, you can circumnavigate the entire perimeter of the flooded Cullinan unit for a full round-trip of about seven miles. Keep an eye out for that trio of levee breaches, especially during an ebb: If you get slurped out of the main pond, hours might pass before you can get back in. And how near you get to noisy Highway 37 on your return leg is, of course, entirely up to you.

As pretty as Cullinan Ranch and the surrounding preserves are now, they are slated to only improve in both size and biologic values.

Don Brubaker, manager for San Pablo Bay NWR, has been the ringmaster overseeing all the changes here for the last six years. In August, he led a public tour of refuge facilities that was tantamount to Cullinan’s coming-out party. “You’re looking at one-fifth of the refuge staff,” he said, as he introduced himself. “Right now, we manage a total of 19,000 acres in the San Pablo refuge, 11,200 acres of which is open water at the north edge of the bay, leased to us by the State Lands Commission.” He waved an arm at the rippling expanse of gold-green vegetation and water that stretched out all around him. “There’s 9,000 other acres inside the refuge’s authorized boundary that we’d like to add, when it becomes available from willing sellers.”

Although Brubaker’s budget, like his official staff, is tiny, robust enhancements and enablers for the expansion project are readily available from a host of highly involved and motivated government agencies and conservation organizations. The latter include the aforementioned Point Blue (formerly Point Reyes Bird Observatory), Ducks Unlimited, and Sonoma Land Trust—which bought and restored the nearby Sears Point Ranch, 1,000 acres at the south end of the Lakeville Highway. (This area was sculpted, breached, and reintroduced to tidal flows at the end of October.) The trust is also working to transfer 1,100 acres of the old Haire Ranch on Skaggs Island to the refuge, adding to the 3,300 acres of the former Skaggs navy base already included.

The former include the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), which is figuring out ways to use dredge materials scooped from shipping channels to raise and sculpt wetlands within the refuge, and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, which manages 15,200 acres of the Napa-Sonoma marshes between Sonoma Creek and the Napa River.

Right now, San Pablo Bay NWR is seen as a little sister to the much larger Don Edwards San Francisco Bay NWR in the South Bay. However, with predicted sea-level rise, dominance in that relationship could shift. The reason? Don Edwards is hemmed in by communities and infrastructure, so it will prove difficult for marshes to migrate inland. Whereas, with the notable exception of Highway 37, the marshes of San Pablo Bay have room to move, and refuge planners are already figuring out how to accommodate rising waters. At which time, San Pablo will be transformed into a major national wildlife refuge in every sense of all four words. And Cullinan Ranch will form one of its most accessible jewels.

“For people who want to see wintering waterfowl and shorebirds, I’d recommend this place, definitely,” Megan Elrod told me as we packed up. “In fact, I’d like to see it added as a site for the winter shorebird census right now.”

In all, I’ve been drawn to visit Cullinan Ranch and its adjacent marshes more than a dozen times, and not always by boat: Some of the best photos I’ve taken here were scored by walking quietly and slowly along the levee trails, or lingering for a while on the viewpoints, so visiting on foot is certainly an enjoyable option. However, it’s those many long, dark sloughs, writhing off mysteriously, deep into the marshes, that beckon me the most this winter, as the clouds of migrating birds return. That allure shall compel me to once again pore over a tide book, pick up a paddle, and go exploring.