The Delta sky is as open as a giant blue eye. A posse of damselflies rides in the lee of my kayak and a hundred geese broadcast their squeaky-barn-door cries overhead. I am less than a mile from the confluence of California’s two greatest rivers and only a stone’s throw from one of the fastest-growing urban areas in the country. This is the intersection of powerful natural and man-made forces: salt and fresh water, land and sea, northern and southern species of plants and animals, an explosion of development, and a tug-of-war over California’s largest supply of fresh water. Yet it is deceptively peaceful here; time seems to have stopped. The blue eye does not blink.

- The rare Antioch Dunes evening primrose blooms for only one night, andonly here, on the remnant sand dunes of the Delta shoreline. Photo byJohn Game.

This is Big Break Regional Shoreline, the 1,648-acre mostly-offshore piece of the Delta that is the newest addition to the East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD). The park is in Oakley, just east of Antioch, and it serves as both gateway to the region’s extraordinary aquatic landscape and a living museum of its ecosystems and wildlife.

Ten thousand years ago, as the glaciers of the last ice age began to melt, sea level rose, filling the low-lying river basin that would become San Francisco Bay and inundating the lower reaches of an immense triangle of wetlands with braids of fresh glacial runoff, seasonal rains, and melting snow. As sea level rose, so did the tules, racing to stay above water. Thousands of generations of the plants piled on top of one another, creating the thick carpet of peat soil that underlies most of the Delta today. It is meters deep and punctuated with mineral-rich layers brought down from the Sierra and deposited by the rivers’ periodic floods.

In this prehistoric era, the ancient Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers entered at the Delta’s northeastern and southeastern corners. As the vast Central Valley drainage flattened out, the rivers lost their single-mindedness, spreading out into great marshes cut by a tangle of sloughs and low, tule-covered islands. The dispersed waters, draining about half of California’s landmass, finally reunited at Suisun Bay and then passed into San Francisco Bay at the Carquinez Strait. When summer’s low flows from the mountains met with high tides from the ocean, salty water would make its way up into the Delta, as far inland as Big Break. It was the ever-moving interface between fresh water and salt water, known as the “null zone,” that made Delta habitats so unusual and led to such extraordinary adaptations in many of the organisms that evolved here.

When Europeans arrived here, the Delta was a place of incredible fecundity. At the bottom of the food chain were huge quantities of phytoplankton that thrived in the shallow waters. The prolific native fish fauna included freshwater species, those that could tolerate salty estuarine waters, and anadromous fish—like salmon and steelhead—that returned from salty marine environments to the fresh water of inland rivers to spawn. The most impressive display would have been the massive annual migrations of chinook salmon that, according to early observers, clogged the Carquinez Strait on their way to their upstream spawning grounds. The most abundant freshwater fish were probably the Sacramento perch (now largely supplanted by alien catfish and carp), hitch, and thicktail chub.

- The Delta is home to California’s largest concentration of beavers. Photo by Jeffrey Rich.

“Before the era of reclamation [the Delta] was a veritable paradise of wild fowl,” says an early California Fish and Game Commission report. Ducks, tundra swans, many kinds of geese, and other waterfowl were all superabundant, says the report. River otters, raccoons, skunks, coyotes, badgers, cottontails and jackrabbits, beavers, tule elk, and bobcats all avoided the giant grizzly bears, which lorded atop the food chain.

Sharing the top of the food chain were thousands of Native Americans who lived along the Delta. They used tule boats to navigate its waterways, hunting elk and waterfowl with bows and arrows, and fishing with spears and nets. The coming of Spanish explorers in the late 1700s undermined the ways of the Delta’s native people. Because the native population’s decline was so speedy, and few of the Spaniards were concerned with anthropology, little is known about the local people of the region, though they resided here for more than 4,000 years, according to anthropologists today. Scientists are currently studying human remains and artifacts that appear to be associated with a village site at Big Break and archaeologists say it may provide insights into the lives of the people who lived here from A.D. 300 until about 1700.

Early European visitors had a profound impact on the Delta’s native fauna and flora as well. By 1800, the once-common grizzly bears were all dead. American and French-Canadian beaver and otter trappers took tens of thousands of pelts out of the region in the 1830s, driving these furbearers to extinction in little more than a decade. The giant herds of tule elk were hunted out by 1850.

- Sunrise at Big Break Regional Shoreline. Photo by Steve Bobzien.

But it wasn’t the pursuit of fur or meat that led to the most fundamental alteration of the Delta. The discovery of gold in the Sierra foothills in the mid-1800s drew thousands of fortune seekers through the Delta up into the hills. Gold mining had a dual impact on the Delta. First, hydraulic mining methods, which used water pressure to “wash” gold out of the hillsides, flushed huge amounts of sediment down into the Delta, where much of it settled over the peat, altering the makeup of the soil and hydrology. Even more important was the subsequent flow of humans; as the Gold Rush tide began to ebb, thousands of frustrated miners returned to settle the San Joaquin and Sacramento River floodplains. Having failed to find wealth in gold, they sought an agricultural paradise instead. The Delta’s floodplains had some of the richest soils anywhere and an abundance of fresh water, a rarity in California. By building an elaborate network of levees against water intrusion, the settlers “reclaimed” islands of dry, fertile land in the shallow sea of Delta wetlands. By 1930, about 550,000 acres had been drained and converted into farmland, much of it below actual sea level. Since then, the Sisyphean tasks of levee building and maintenance has continued unabated.

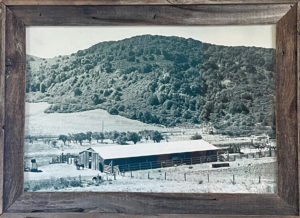

Big Break itself was “reclaimed” from marsh in this way in the late 1800s when farmers built levees against the waters of Dutch Slough and the San Joaquin River. The marshland was pumped dry and asparagus planted and grown there for decades. In 1928, portions of the levee crumbled following heavy rains, causing a “big break.” Water rushed in and two-and-a-half square miles of asparagus were lost. By the time the owner pulled together enough money to repair the levee, the state had annexed the now-submerged farmland as a part of its waterway system.

In the 1950s, federal and California water projects, among the biggest of their types in the world, began diverting huge quantities of water from the Delta, reducing the flow of freshwater through Carquinez Strait by about half in dry years. With all the diking and diversions, the Delta of today is largely an artificial environment. The uninterrupted miles of marsh and tangled sloughs are gone, replaced with orderly farms, framed by elevated roads, and laced with waterways. Most of the latter are channelized and businesslike, though a few still follow their original, aimless contours.

These changes have had a big impact on the Delta’s plants and animals. For instance, there’s the Delta smelt, a tiny, steel-blue fish that relies on the Delta’s null zone, where salt water and river water meet: Its eggs hatch upstream, but its larvae spend the summer eating zooplankton in the shallow marsh areas near Big Break. When the state’s water project draws too much water out of the Delta, the null zone moves upstream, disturbing the smelt’s ability to reproduce. The Park District hopes to manage this smelt habitat in a way that will maximize its value to the species.

The Delta’s native species also face competition from invasive aliens, such as the Chinese mitten crab, which first appeared in the Delta in the 1990s and has made its way as far upstream as Big Break. The predominant plant in the aquatic portion of Big Break today is an exotic form of water hyacinth, which has choked out many natives. On land, introduced red foxes, feral cats, and starlings are among the creatures that have displaced many natives.

While human hands have radically altered most of the modern Delta, there are still a few places reminiscent of the richness and wildness of the old days. Unfortunately, public access is notoriously scarce. The East Bay Regional Park District is hoping to change that. For instance, plans to install trails, a boat launch, and a science center at Big Break should help give amateur naturalists a way in to this extraordinary place.

The shallow aquatic part of Big Break is shaped like a two-and-a-half-mile-long, one-mile-tall boar, its squarish snout facing east. The pig’s tail touches the San Joaquin River almost where it meets the Sacramento. On its southern border, Big Break’s waters are rimmed by freshwater marsh, also now managed by EBRPD. Very few acres of freshwater tidal marsh remain intact in the Delta, making those at Big Break an extraordinary asset.

At its southwest corner, beneath the boar’s tail, is the Lauritzen Site, the 40-acre upland portion of the new park, home to 12 special-status (state or federally listed) plants, including heartscale, rose mallow, and Delta mudwort. The Antioch Dunes evening primrose is one delicate and unobtrusive plant whose white and pinkish flowers unfurl at dusk on their one-night-long chance to be pollinated. With the break of dawn, they blush and wilt. The nearby, postage-stamp-size Antioch National Wildlife Refuge, one of the primrose’s last holdouts, is surrounded by a mine, a power plant, and a wallboard factory.

The primrose is one among several rare species that rely on sand dune islands in the Delta. Thousands of years ago, when sea level was lower, the Sacramento and San Joaquin flowed as rivers all the way to Suisun Bay, where the funneling of their waters at Carquinez Strait caused the deposition of sand that had accumulated in the rivers as they traveled from the Sierra Nevada. Winds off the Pacific drove that sand back upriver, dropping it near modern-day Big Break and forming islands of dunes in oceans of peat. It is here, in remnant pockets of these dunes, that the Antioch Dunes evening primrose resides. The California silvery legless lizard also takes refuge here. Although the lizard does not occur at Big Break, the EBRPD maintains dune habitat in the Legless Lizard Preserve, about a quarter mile south of the park.

Seventy bird species are known to live at or visit Big Break. It is common to count over 30 species, from raptors to sparrows, in a couple of hours there, says park naturalist Mike Moran. On the Lauritzen Site alone, white-tailed kites, yellow-breasted chats, northern harriers, and black rails all nest. The last two present a special management challenge: Both are listed species, but northern harriers are unmoved by the plight of the rails and eat as many as they can get their talons on.

Another EBRPD park about 20 miles west of Big Break, Martinez Shoreline, is also an excellent place to view birds. There are recreational areas, including a famous bocce court (where mostly older birds in white cotton plumage gather), but there is also a restored marsh area near the outlet of Alhambra Creek. It is close enough to the Bay that the water is much saltier than at Big Break; hence salt-tolerant pickleweed, dodder, and salt grass dominate. One of the restoration’s primary objectives was to make more habitat for the federally listed salt marsh harvest mouse, which is notoriously difficult to see. However, there are exceedingly visible snipes, avocets, egrets, killdeer, western sandpipers, hawks, white pelicans, and a huge variety of ducks that populate the park’s new marsh.

If Martinez Shoreline is too public, a short paddle from the Pittsburg Marina will get you to Browns Island, another East Bay Regional Park. Here, a network of sloughs penetrates the island’s dense tules and blackberry thickets, giving access to some excellent wildlife viewing and a sublime sense of solitude. Otters and muskrats frequent the island, as do harriers and kites and ducks. Marsh wrens and red-winged blackbirds are common there, and it’s possible to catch site of the rarer tricolored blackbirds, too.

And then there are the beavers that excavate their homes in the levees and islands—such as Browns—throughout the Delta. I’ve been exploring and writing about California wildlife for more than a decade, but I was amazed and delighted to learn that the state’s highest concentration of beavers was in the Delta, only about an hour from my Oakland home.

It is in pursuit of some quality time with these waterborne members of the rodent family that I have come out once again to Big Break’s Lauritzen site. I pull my kayak ashore and throw my sleeping bag under a grove of cottonwood trees near a little marsh inlet. I take a seat beneath the trees as the setting sun casts shadows from the water’s whitecaps. A tree, recently downed by the beavers, stretches out over the water halfway to the intriguing wreck of a clam-dredge barge. With darkness comes the creaky heartbeat of calling crickets. I sit, notebook in my lap, and wait to catch sight of the bucktoothed wonders.

Just after the first stars appear, a beaver’s V-shaped wake glides silently across the water in front of me. When I approach the shore for a closer look, the beaver whacks its tail on the water and disappears. It’s 20 minutes before it reemerges, followed a few minutes later by two or three others. It’s more than fun watching them come and go, criss and cross in the water, busy as, well, beavers. These playful mammals, the largest rodents in the world, are considered pests by many Delta residents, given their penchant for undermining the integrity of levees and damming irrigation channels. Maybe it’s an instinctual sort of civil protest. After all, they’ve been here a lot longer than people have, and may well know something we don’t about how the Delta ought to be.

The breeze rises with my mood and it begins to whirl gently through the trees. Much later, as the night grows old and I leave the beavers to their happy business for the comfort of my sleeping bag, the gentle rustling of cottonwood leaves becomes a pulsing roar and I am swallowed whole by the Delta’s nocturnal rhythms.

Getting There:

Big Break Regional Shoreline will soon feature multiple trails, a boat launch, parking, rest rooms, and the Delta Science Center, a floating research and public education center currently in development. For the moment, hiking and biking access is limited to a mile-long paved trail that offers splendid views of freshwater marsh and is an excellent place to see all kinds of birds. Street parking is available at the trailhead, at the intersection of Jordan and Fetzer. From Highway 4 (Main Street) exit in Oakley to Vintage Parkway, turn left, cross railroad tracks to Walnut Meadows. Turn right on Walnut Meadows, follow to Jordan Lane, turn left, and proceed one block.

.jpg)