If you’re driving north on Highway 101 from San Francisco, you first see Sonoma Mountain as you approach Petaluma: an abrupt and massive upswelling of the terrain, more like the prow of a great ship than a peak. It dominates the eastern horizon all the way to Santa Rosa, changing constantly with the light and the season. This part of the North Bay is heavily populated, the lowlands a vast tessellation of exurbs, vineyards, and pastures. But from the freeway, the flanks of the mountain look almost untouched. Dark woodlands are interspersed with rolling uplands, golden in the summer and fall, green as emeralds and jade during winter and spring. The mountain looks wild, and it looks close. It seems that a short hike could take you from the congestion of the 101 corridor to a different time and place.

This is not mere illusion. Sonoma Mountain is wild, and its wildness is all the more precious for its proximity to Petaluma and Santa Rosa. I speak here from experience. I lived on the mountain’s heavily forested north slope for more than 10 years, in a small cabin on a 35-acre vineyard—or “grape ranch,” as the local parlance had it. We heated with eucalyptus and oak from the property; we raised most of our food. I could look down to Santa Rosa, seven miles away, with its traffic, noise, commerce, and congestion. But from my vantage, it was just a static diorama; I heard nothing but the soughing of the wind through the black oaks. I was reluctant to leave the mountain, even for necessary shopping or business. Everything I wanted, and most of what I needed, was there.

I tracked the mountain’s … not cycles so much, but fluctuations. Some years, the deer, or the gray squirrels, or raccoons, or valley quail, were up. Others, they were down. One year, feral pigs rampaged through the vineyards and gardens. During some winters, mallards, widgeon, and scaup were thick on the pond the owner used for irrigation. Others, they were almost absent. One duck-related incident remains particularly vivid. The pond teemed with small bluegills, the descendants of a few fish dumped there long ago by the kid of a neighboring rancher. One cold winter morning, I strolled down to the pond and found it carpeted with common mergansers. They were conducting a mighty slaughter, consuming the bluegills as fast as they could cram the fish down their gullets. They fed for three days, then abruptly decamped, leaving nothing but a few floating, finned carcasses.

Other memories intrude whenever I look at the mountain—which is often, given that I now live in Santa Rosa. I remember the varied thrushes flitting through the California laurel and redwood groves in late winter and the Bullock’s orioles trilling in the eucalyptus lining our driveway in the spring. I remember the lust-crazed black-tailed jackrabbits chasing each other through the vineyards once winter had broken—literally mad as March hares.

I must admit I found the mountain’s enforced isolation attractive. In other words, I enjoyed the fact that people were largely excluded. Virtually all the mountain was privately owned; there was no public access. I could roam at will, because the grape rancher was friends with all the neighboring property owners. But I also felt, deep down, there was something inequitable about this arrangement. Sonoma Mountain was and is too great of a treasure to be hoarded. Somehow, there had to be a means of allowing access while protecting its incomparable beauty and largely intact natural systems.

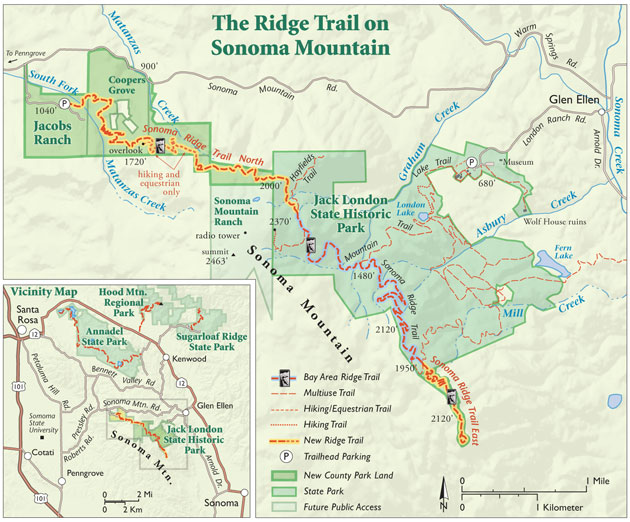

That was — more than two decades ago. For all those intervening years, most of Sonoma Mountain has remained off-limits to the public. But that’s about to change. Soon, you’ll be able to hike more than eight miles across the mountain, from a trailhead at Jacobs Ranch on the northwest slope to Jack London State Historic Park on the northeast side of the mountain. The trail, the end product of a collaboration of the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District (SCAPOSD), Sonoma County Regional Parks, the Bay Area Ridge Trail Council, LandPaths, and the state Department of Parks and Recreation, is largely completed and is a linchpin component of the regional Bay Area Ridge Trail.

I recently hiked the new Ridge Trail segment on the mountain’s north slope with John Aranson, trail steward for the Bay Area Ridge Trail Council. Aranson, as his title implies, knows trails: He was the field inspector during construction, monitoring everything from the route surveys to the construction of the elaborate rock drains that divert water from the trail to minimize erosion.

We met at the Jacobs Ranch, the trail’s staging area, not far from the hamlet of Penngrove. This property, formerly owned by the late Sonoma Mountain cattleman Bill Jacobs, was acquired by SCAPOSD in 2003. I had known Bill. He was a massive man, with a chest like a keg, hands that could grip a basketball like a grapefruit, a booming foghorn voice and an omnipresent 10-gallon hat jammed down on his head. It was strange to visit the ranch in his absence. I half expected to see him striding from the ranch house where a park ranger now lives, bellowing a greeting, one hand raised, the other grasping some horse tack or a hay hook.

“To a real degree, ranchers kept this area undeveloped,” Aranson says. “It was their early stewardship that ultimately made the establishment of the trail possible.”

The trail was engineered with moderate gradient and minimal environmental disturbance in mind, and it traverses virtually all the mountain’s diverse and lovely biomes. Rather than attempting to dominate the natural topography of the mountain, the trail accommodates it. In the rare instances where switchbacks are necessary, they are long and gentle. As noted, expertly constructed rock drains divert water away from the route. Walls of pressure-treated lumber reinforced with h beams maintain the trail’s gradient across steep and unstable ground. In cases where significant excavation was necessary, the overburden was moved to stable locations near the trail, contoured with the existing slope, and seeded with native annuals and perennials.

“We had a licensed contractor handle most of the construction, but we also used Conservation Corps North Bay crew members and local youth volunteers wherever possible,” Aranson says. “Sonoma County has a huge trail and open space constituency, and a project this ambitious generates a lot of support and excitement.”

Our hike took place in mid-spring, and the mountain was at the peak of its vernal glory. Despite the drought, the slopes burned with a dazzling palette of greens. A few last puffballs yielded their spores at the margins of the track, and wood satyr butterflies flitted among lush stands of yarrow, lupine, blue-eyed grass, California poppies, and buttercups. We followed the trail across broad meadows, past several vernal pools, and through groves of bay laurels and black oaks. Redwoods grew along the Matanzas Creek gorge, and as we gained elevation, we passed into a mixed woodland of Douglas fir and madrone.

At one point, we saw a large flock of turkeys ghosting through the trees, and later we heard the crazed yammering of a pileated woodpecker. We walked through an expanse of small, twisted oaks and native bunchgrasses growing between piles and windrows of volcanic stone covered with moss and lichen. The scene almost looked cultivated, like a meticulously tended Kyoto rock garden. One of the oaks supported an active honeybee colony. The air around the tree was perfumed by honeycomb and pollen and resonated with the low susurrus of returning bees. And at every open vista, we were treated to spectacular views of the Santa Rosa plain, nearby Taylor Mountain, and the Mayacamas range to the east. Far to the west, the coastal mountains lined the horizon, and turkey vultures and red-tailed hawks wheeled on thermals across the bowl of the sky.

In short, the trail is spectacular, and it seems inevitable that it will become a priority destination for hiking and equestrian enthusiasts regionally and beyond. But again, such a remarkable recreational resource begs a couple of questions: How do we preserve it? As its reputation grows, could we end up loving it to death?

“This is a fairly long trail in a sensitive environment,” says Kim Batchelder, the natural resources planner for SCAPOSD. “This isn’t a build-it-and-forget-it situation. Monitoring impacts on an ongoing basis is an essential part of trail management. We’re committed to ongoing evaluations of everything from erosion to wildlife movement.”

I had noticed several small cameras discreetly placed along the trail. Batchelder confirmed they were integral to research on the mountain’s wildlife. “Sonoma Mountain supports both a rich diversity and large numbers of wild animals, including black-tailed deer, coyotes, mountain lions, and bobcats,” Batchelder says. “The cameras are motion-activated, and they’re providing excellent data on animal distribution that will really help managers protect the mountain’s wildlife.”

Completing the trail required that scaposd acquire 783 acres on five separate properties. While the district is now in the process of transferring ownership of the land to Sonoma County Regional Parks, SCAPOSD will retain the conservation easement for the property.

“We’ll do regular site visits to ensure that the terms of the conservation easement are met,” says Sheri Emerson, the stewardship program manager for scaposd, “but long-term land ownership and day-to-day management fall more within the portfolio of Regional Parks.” A Sonoma County Regional Parks ranger is permanently stationed at the former Jacobs Ranch and the department is eager to open the new property to the public. “This park will be amazing,” says Caryl Hart, director of the regional parks department. “It’s adjacent to densely populated areas, but has a real wild feeling, and it gets people close to the top of Sonoma Mountain, where the views are phenomenal.”

From the beginning, says Emerson, the trail “has been a collaboration. The Open Space District, Regional Parks, the Ridge Trail Council, State Parks, LandPaths, and the State Coastal Conservancy, all contributed. So did the Jacobs family and other landowners who wanted to see the essential character of Sonoma Mountain preserved. It took about 18 years to put all the pieces together, and it wasn’t always easy. Without everyone working together, public agencies and private citizens, this never would have happened.”

Bill Keene, SCAPOSD’s general manager, observes that such partnerships made it possible for his agency to do what it does best: punch above its fiscal weight. “We employ a variety of funding mechanisms,” Keene says, including “the district’s unique local sales tax revenues — which we also use to obtain matching funds from other sources. Basically, it’s about leveraging funding to that point where large, important projects like the north slope Ridge Trail can move forward. We couldn’t do it alone. Our partners are essential at every juncture.”

For Aranson, this new trail closes a critical gap in the larger Bay Area Ridge Trail route. But he’s hardly resting on his laurels. “Now we need to close the four to five miles that will connect us from Jack London State Park to Annadel State Park, where there are about eight miles of dedicated Ridge Trail,” Aranson says. “When the project is completed, we’ll have some 550 miles of trail circling the Bay Area. So far, we have nearly 350 miles. We aren’t going to finish this in my working lifetime, but I know we’ll get there eventually.”

Part of getting there will be the dedication, in spring 2015, of the mile-long east slope Ridge Trail segment, which will adjoin Jack London on the mountain’s southeastern flank and bring the total length of the Ridge Trail on the mountain to over nine miles. It also moves the Ridge Trail one mile closer to connecting Sonoma Mountain with Petaluma Valley, but that’s a future story.

Certainly, it will be a remarkable thing to be able to hike the circumference of the entire Bay Area, from Morgan Hill to Calistoga. But there’s no need to wait; the benefits of the work of the Ridge Trail Council and its partners can be — should be — enjoyed now. Each leg accessible to the public offers respite from the travails and stresses of urban life. And if the entire Bay Area Ridge Trail can be viewed as a crown that is slowly being fitted to the region’s brow, the Sonoma Mountain Ridge Trail will shine as one of its loveliest gems.

During my hike, we stopped for lunch in a narrow declivity shaded by Douglas firs and hardwoods, next to one of Aranson’s delta-shaped rock drains. It was a masterpiece of stone masonry, and it was a pleasure to eat my sandwich and contemplate its meticulous joinery. Some bushtits squabbled in a thicket of laurel behind us.

The air was sweet with the tender vegetation of late spring. It tasted green and pure. I was flooded with memories: of Bill Jacobs and other mountain residents. Of the faint soundings of a gong at daybreak, calling acolytes to meditation at Genjo-ji, the Zen monastery up the road. Of black phoebes and western bluebirds perched on the grape stakes of the vineyard. Of dozing in front of a woodstove charged with blazing eucalyptus while a freezing rain pounded the tin roof of my cabin.

I realized I would never live on the mountain again, and the thought was deeply melancholic, like remembering a great amour, or the passage of youth. But very soon, this trail will be open to the public. I can come back whenever I want. I can visit. And maybe that will be enough.

Check ridgetrail.org for updates and news about other new and existing trail segments.

-300x244.jpg)

-300x162.jpg)