he origins of great ideas, the moments of inception, are always hard to pinpoint. The environmental movement, for example: did it begin with Earth Day in 1970, or with Rachel Carson and her publication of Silent Spring in 1962? Young historians, still wet behind the ears, sometimes argue for these dates. “Way too late,” old-timers in the movement insist. They suggest that a better case can be made for 1949 and Aldo Leopold’s publication of A Sand County Almanac, in which that great forester spells out his “land ethic.” Or even earlier, 1924, when Leopold established our first designated wilderness, the Gila, 872 square miles in which Aldo’s ideas about our moral obligation to the land acquired territory, an actual foothold on the Earth. And then there is Thoreau, Leopold’s literary and philosophical inspiration. A case can be made that environmentalism began in 1854 with Walden and Thoreau’s musings beside that pond.

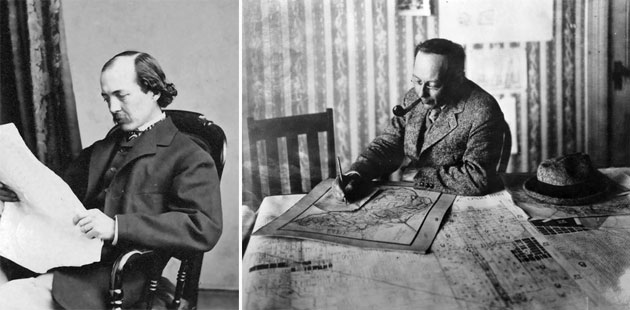

IN 1863, NOT A YEAR AFTER Thoreau’s death, Frederick Law Olmsted, king of American landscape architecture, looked into the hills east of San Francisco Bay and saw that they were good. He imagined a park up there.

Seven decades later, in 1930, Olmsted Brothers, the nation’s first landscape architecture company—a firm founded by the great man and now run by his sons, Frederick Law Jr. and George—drew up a plan, “Proposed Park Reservations for East Bay Cities.” Their scheme would grow far beyond anything any Olmsted ever imagined. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD), a far-flung system of 65 parks. If this great experiment, or binge, in park creation had a moment of inception, then perhaps it came as Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. faced east toward the hills.

The year 1863 had been a busy one for Olmsted. In spring he wrote up a prospectus and sought funding for The Nation, a progressive journal that still thrives, our oldest continuously published magazine. His plans for Central Park in Manhattan—he was both designer and superintendent—had been put on hold by the Civil War but were still percolating in his imagination. In August 1863 he resigned his post as general secretary of the US Sanitary Commission, where for three years he had been responsible for sanitation in all camps for Union Army volunteers, and he headed west to run the Mariposa Mine in the Sierra Nevada.

Visiting Yosemite, next door to Mariposa, Olmsted was smitten. In the valley he saw an apotheosis of the harmony and wholeness for which he always strived in his landscape architecture. Yosemite was “the union of the deepest sublimity with the deepest beauty of nature, not in one feature or another, not in one part or one scene or another, not in any landscape that can be framed by itself, but all around.” In 1864, when Lincoln ceded Yosemite to California, Olmsted became one of the commissioners charged with oversight of the new reserve. His 1865 report, “The Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove,” was the finest expression yet of what would eventually become the national park idea. Yosemite, he wrote, should be a refuge for the physical and spiritual health of the people. It should be a park for everyone and for all posterity. It should be an exercise in democracy; in fact it was an obligation of the democratic state. Parks, he wrote, are about the pursuit of happiness, and he shrewdly identified the enemy: “It is the main duty of government, if it is not the sole duty of government, to provide means of protection for all its citizens in the pursuit of happiness against the obstacles, otherwise insurmountable, which the selfishness of individuals or combinations of individuals is liable to interpose to that pursuit.”

FROM HIS MARIPOSA MINE, Olmsted occasionally retreated for R & R to a house he owned in San Francisco. Asked by the College of California to review plans for a campus near the village of Berkeley, and then design a park for it, Olmsted tossed the whole scheme. The site, facing San Francisco, was nice, he said, “judiciously chosen,” but the plan was defective all the same. “Although it has the advantage of being close by a large town, however, the vicinity is nevertheless as yet not merely in a rural but a completely rustic and almost uninhabited condition, two small families of farmers only having an established home within half a mile of it.”

The first requirement of a revised plan, Olmsted wrote, would be inducements to build a neighborhood of “refined and elegant” buildings around the college. Olmsted had a place in his heart for refined and elegant buildings—he was, after all, an architect—but his passion was parks. What he really cared about was that “rustic and uninhabited condition” to the east. In his imagination he could see a road extending from the college toward the rustic hills. To either side of the imagined road, along the stream it followed up into the hills, a park took shape in his head.

ENVIRONMENTALISM HAS NO CLEAR MOMENT of inception, maybe, but it has its terrains. The wooded shores of Walden Pond, in Massachusetts; Aldo Leopold’s farm in the sand hills of Wisconsin; Yosemite and Yellowstone; the region around San Francisco Bay, where so much of modern environmentalist theory and activism had its start. The 115,000 acres and 1,250 miles of trails in the East Bay Regional Parks grew out of that local fervor and they substantiate it. With establishment of these parks, the environmental movement here became landed; it acquired territory, an actual foothold in the California earth.

On Wednesday evenings for the past eight years, a small group of EBRPD enthusiasts have met in the archive at the old headquarters on Skyline Boulevard in Oakland, where, gathered in a kind of quilting bee, they attempt to whip the Park District’s history into shape. Recently I dropped by to interview three of the participants. Presiding was Jerry Kent, burly and Falstaffian, a manager who worked forty-one years for the District and then, upon retiring a decade ago, immersed himself in its history and became an acknowledged expert. The second quilter was Richard Langs, slimmer and less Falstaffian, a retiree from the transportation industry who is writing a history of Tilden Park. Langs wears a mustache somewhat fuller than the pencil mustaches popular in the 1930s, when Tilden Park originated, but somehow evocative of that time. The third quilter, Brenda Montano, works in public relations for the Park District. She did not seem anachronistic in any way, except maybe for a vaguely thirties-style pin curl in a couple of ringlets of her hair. The archive is Brenda’s domain.

“I STARTED WORKING here in 1962,” Jerry Kent told me. “I made up history my whole career at the district. Some of it’s accurate and some of it’s not. So Richard and Brenda are here to make sure it’s accurate.”

“You made it up off the top of your head?” I asked.

“Sure. When you’re the assistant general manager, you can just say something, and people believe it.”

It was good, then, that Richard and Brenda were on hand to keep their colleague’s imagination in check. I opened my notebook to the first of my questions: If they had to pick a moment of inception for the Park District, I asked, what would that be?

“Robert Sibley,” said Kent. “He was chair of the Contra Costa Hills Park Association. Robert Sibley, as soon as he learned that EBMUD [East Bay Municipal Utility District] was going to get rid of 10,000 acres.”

“A light went on?”

“Yes. Sibley was a UC grad, and he had a heart condition. His doctor told him to go hike in the hills. He would go up to the end of Euclid Avenue, go over the fence and the ‘No Trespass’ signs that East Bay MUD had out, and hike in the hills. As soon as he heard they were for sale, he wanted to preserve them. It was either going to be real estate development, or it was going to be preserved as a park. Sibley was probably the light that got it going.”

Richard Langs shifted in his seat and cleared his throat. “I differ, a little bit,” he said. “The light was Arthur Davis.”

“Arthur Davis?” said Kent. “Who’s Arthur Davis?

“Arthur Davis was the chief engineer for East Bay MUD.”

“Engineers don’t have lights go off in their heads!”

Everyone laughed at the truth of this observation—or, if you like, laughed at Kent’s gleeful expression of this unfair stereotype. Then Langs defended his theory: “When EBMUD was successful at completing Mokelumne Dam in the Sierra, or Pardee Dam, as it’s now called, some of the local watershed became surplus. Arthur Davis, without getting permission from the EBMUD board, sent letters to the mayors of the cities. ‘This land’s going to be available. It’s up for grabs.’ There had to be a park idea in his head. For this he got in a fight with George Pardee, the president of the EBMUD board, and he left. He went off to Russia to do water projects there.”

Jerry Kent remained skeptical that Arthur Davis belonged among the District’s founding fathers, but he was willing to listen. I loved the Arthur Davis story, myself. For one thing, it was an anecdote. I was desperate for a few of those, for the lives of many figures in the early history of EBRPD had proven disappointingly sketchy. Here at last was a fragment of narrative. Arthur Davis was a nephew of the great John Wesley Powell, explorer of the Colorado River and founder of the federal agency that would become the Bureau of Reclamation. Davis himself had served as director of that bureau and had planned several dams for the Colorado before coming out to California to work for EBMUD. Davis, in spilling the beans about the surplus land for the good of the public, had risked the enmity of George Pardee, EBMUD president and former governor of California. For his troubles Davis had been banished to water projects in Siberia, or thereabouts. For another thing, I liked what the Davis story had to say about the small contingencies that jigger the course of history—suppose those letters to the mayors had never been dropped in the mail? For a third thing, any enemy of George Pardee was a friend of mine. In the 1902 election for governor of California, Pardee had crushed the Socialist candidate, Gideon Brower, my great-grandfather, by 146,332 votes to 9,592.

“RICHARD’S PROBABLY RIGHT,” Kent conceded. “Did the light go on in just one person, or did it go on in a whole bunch of people?” We tossed that one around for a while. Then Kent asked another question, for me the best one of the day.

“Why was the Olmsted Brothers plan successful here in the East Bay,” he wondered. “When their park plan for Los Angeles failed? Up here they did a little $5,000 study that took six months. Down there they spent two years doing an $80,000 study for Los Angeles County. Here it succeeded. Down there it was pigeonholed and died.”

Solving Kent’s riddle, I realized, would be a clean way to frame my EBRPD story. In the next days, talking the matter over with Brenda Montano’s archive team and other park staff interested in EBRPD history, I distilled a two-part theory for the success of the East Bay’s regional parks: Plumbing and Community.

Plumbing was the lesser factor, but it played a role. East Bay parks were lucky, Richard Langs pointed out, in how fast Pardee Dam and its aqueducts were completed and came on line, delivering Mokelumne River snowmelt to East Bay reservoirs. “They beat San Francisco and Hetch Hetchy Dam,” he said. “It took them just four years, instead of the fifteen for Hetch Hetchy.” The 10,000 acres of watershed in the East Bay hills became available at just the right moment, as other ducks were lining up in a row. (The fact that those acres were water district land did not hurt either; the land necessary for the Olmsted park plan in Los Angeles was in private ownership, a much more difficult and expensive proposition.)

But community was what truly made the difference. A convergence of forces in the East Bay—the nascent conservation movement, engaged scholars at the University of California, and resident expertise on national, state, regional, and urban parks—combined to make fertile soil for the seed of the regional park idea.

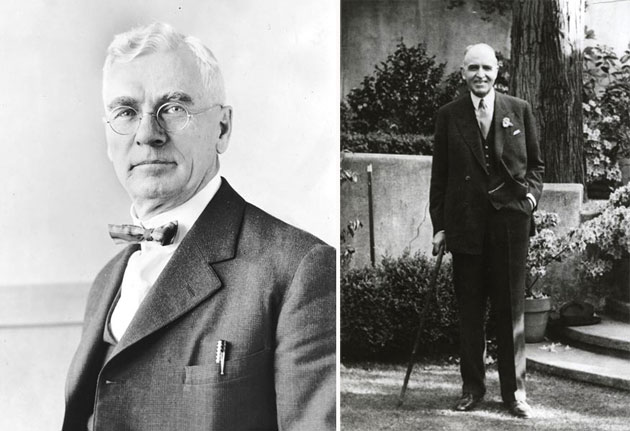

For the conservationist faction, the realtor Duncan McDuffie was point man. Tall, distinguished, eloquent, an eminent residential developer in the Bay Area, McDuffie was also an outdoorsman. He loved the Sierra Nevada and had wandered the range with Little Joe LeConte, the UC professor who had cofounded the Sierra Club and who, upon Muir’s death, became its second president. In 1908, LeConte and McDuffie spent a month hiking and mapping a 230-mile route across the High Sierra from Yosemite to Kings Canyon. McDuffie made the first ascents of Mount Abbot, 13,736 feet tall, and Black Kaweah, 13,754. He was a man who knew his way around in the wilderness. As with Olmsted, his experience of wild nature informed his philosophy on space and landscaping in his projects.

“MCDUFFIE WAS A UC ALUM,” Jerry Kent told me. “He was president of the Save the Redwoods League and became president of the Sierra Club. He was chair of the California State Parks Committee, which began lobbying to create a California park system in 1927, and he chaired the $6 million bond campaign for that cause. That same year, 1927, Clement Calhoun Young became governor of California. McDuffie had employed Young at Mason McDuffie, so he had an in with the governor, who referred to the realtor as his ‘park man.’ McDuffie also knew Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. He had used Olmsted to design some of his residential developments. In 1927, at McDuffie’s urging, Olmsted Jr. was hired to do the state park plan at the same time he was designing the plan for Los Angeles County. Then in 1929, those two plans completed, McDuffie telegraphed Olmsted Jr. requesting that he prepare a park plan for the surplus EBMUD land.”

Olmsted came up from Los Angeles and met in Berkeley with McDuffie, Robert Sibley, and UC political science professor Samuel May, who, as director of the UC Bureau of Public Administration, had obtained a $5,200 grant to pay for the report. On hand as well was Ansel Hall of the National Park Service.

“Olmsted Jr. had encountered problems with his Los Angeles park plan, just as his father had years earlier with his plan to make Yosemite a state park. In both cases, powerful political and economic interests opposed these beautiful plans and buried them,” Bob Doyle told me, picking up the story later. Doyle, who has worked for 35 years in the EBRPD, is now in his fourth year as general manager.

“So Olmsted was suffering the loss of this fine, visionary plan. He had to be convinced to do this little Podunk plan for the East Bay parks. I’m sure McDuffie had a big role in that. He and Olmsted were friends, and they were connected through their work on the state park plan. But the bigger role, I think, was Ansel Hall’s.”

Hall had graduated from UC in 1917 with a degree in forestry. He started his career in the National Park Service, an agency then just one year old, with a brief stint as a ranger in Sequoia National Park. He left to fight in France in the First World War, then returned to become park naturalist in Yosemite. He rose quickly through the ranks: chief naturalist for the NPS, then senior naturalist and chief forester—the first to hold that position—and finally chief of the Field Division. He was a great teacher, creative thinker, charmer, and fund-raiser. In 1929, when Olmsted Jr. came up to Berkeley to meet with the backers of East Bay parks, Hall was dispensing advice to state and local park agencies out of NPS Educational Headquarters at 213 Hilgard Hall.

“I think this story’s remarkable,” Bob Doyle told me. “Because nobody even thinks about it—that national parks had such a role in Berkeley, or that Berkeley had such a role in national parks. The first naturalist in Yosemite ends up having an office at UC Berkeley! And the naturalist ends up being the one sent out to scout the hills and reassure Olmsted. It was really Hall. He was the one to say, ‘Yeah, this is worth a plan! These would be really nice parks.’”

Hall would confide to his son his own opinion on who dreamed up the parks. Not Sibley, or Arthur Davis, or any Olmsted. The idea for the 22 miles of ridgetop parks, he told the boy, was his own. The park study, researched and written by Ansel Hall and George Gibbs, a planner with Olmsted Brothers, was approved by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and published in December 1930. The new park system was conceptually launched.

Robert Gordon Sproul, president of UC, represented the university in the fight for parks, heading up the successful election campaign for formation of the EBRPD. But the truth is that almost all the campaigners—McDuffie, Sibley, Hall, May, and many others—were graduates or employees of the university. They were interconnected with one another, as well, and they overlapped in their affiliations.

In studying the resumés of the protagonists, I am struck by how times have changed. Many of the principals in the creation of the Park District were developers: McDuffie, the Olmsteds, George Gibbs. They were Republican businessmen. It was an age when “conservatism” and “conservation” resonated not just phonically but ideologically. That age is now cold and dead. One wonders why this had to be. Was a Duncan McDuffie possible only because California was still roomy enough that both dreams could exist in one head?

If one man, in his person, subsumes all the convergent forces that spawned the East Bay Regional Park District, then my candidate is Frederick Law Olmsted the First. Olmsted was an academic, a nature lover, a progressive, an urban park specialist, a national park innovator. Jerry Kent does not consider either Olmsted to be a founder of the Park District—Senior came too early, in Jerry’s opinion, and Junior was too remote from the action. Kent favors what he sometimes calls “the water carriers” and other times “the heavy lifters.” The boots on the ground. The people who got it done.

Bob Doyle, who now manages the legacy of the District, seems to lean toward a broader definition of authorship.

“From the first time Olmsted Sr. laid his eyes on the East Bay hills in the 1860’s the idea of parks in those hills never went away. The Organic Act, which established the National Park Service, and which Olmsted Jr. helped write, came in 1916,” he told me. “And in 1927 came the state park plan. And in 1930 came the East Bay Regional Park plan. Olmsted’s key lines in the Organic Act, about public enjoyment and physical stimulation, and so forth, were definitely incorporated into the thinking of this Park District I manage. It’s just there. It’s all over it, whether you see his signature there or not.”

FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED, FATHER AND SON, transformed how we think about parks. We need muddy boots on the ground—can’t do without them—but we also need visionaries and prophets who change the very air we breathe.

Berkeley-based nonfiction writer Kenneth Brower, the eldest son of environmental leader David Brower, is the author of more than a dozen books about people and the environment. His latest book is Hetch Hetchy: Undoing a Great American Mistake (Heyday, 2013).