In a moment of nighttime wakefulness on a late-winter backpack trip, I look skyward through the arching branches of the surrounding blue oaks. Deneb, Altair, and Vega, the corners of the Summer Triangle that will dominate the evening sky several months from now, are overhead. Seeing this iconic stellar feature this time of year means morning’s first light can’t be far away. I’m only about 25 miles from downtown San Jose, but the path of the Milky Way through the Summer Triangle is as crisp and bright as if I were on a desert island. I have seen no one in days, and there is likely nobody within 10 miles of me. I am as alone as I have ever been.

At morning’s first gray light I sit up to look across a gentle rolling landscape. Winter rains have greened the grasses and renewed the South Fork of Orestimba Creek, which is sliding gently past me on its way to the Central Valley and the San Joaquin River. The warmth of the sun rising above Mustang Peak finally lures me from my sleeping bag. In utter stillness and silence, I munch my granola, thinking only of which direction to wander.

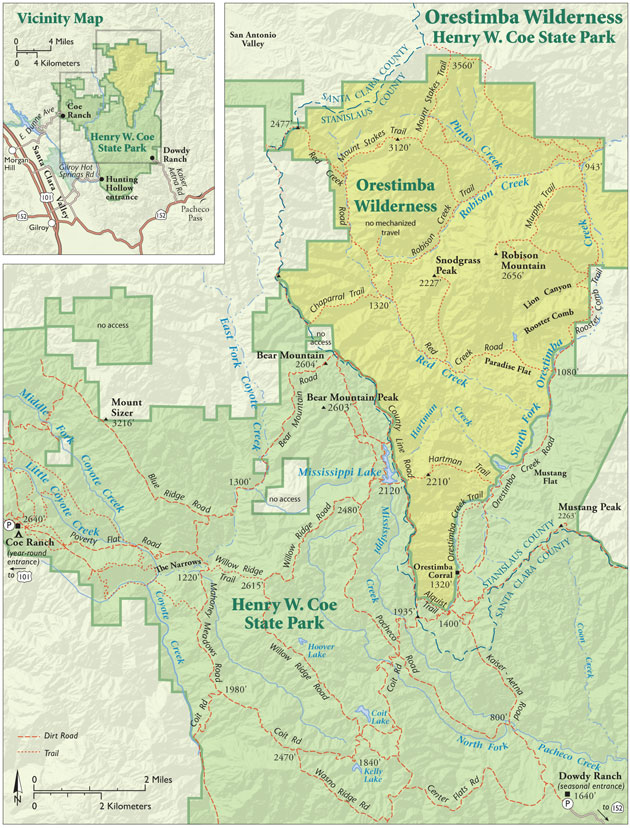

This landscape and this solitude wait in the heart of the Diablo Range south of Mount Hamilton. The 22,000-acre Orestimba Wilderness, tucked away in the remote northeastern portion of Henry W. Coe State Park, is one of the Bay Area’s most secluded natural areas. Moments of utter solitude are the Orestimba’s calling card. Wherever you might travel in the American West, you are not likely to find a place more isolated.

The special solitude of the Orestimba Wilderness is no accident. The boundary to most wilderness areas is just steps away from a parking area, but when you leave your car at Coe Park headquarters, you are still 12 tough miles from Bear Mountain and your first view of the wilderness. To get there, you must cross steep and rugged country over trails that were formerly ranch roads, cut at steep gradients that can break a hiker’s heart.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

GETTING THERE:

The Dowdy Ranch Visitor Center and park entrance, seven miles from Highway 152 on a dirt road, is generally open on weekends but check coepark.net for current status. Park headquarters is on the west side of the park, 14 miles east of Highway 101 at Morgan Hill.

Coe Outings are volunteer-guided excursions into the remote eastern portion of Coe Park. Info at coepark.net.

Gavilan College Community Education offers occasional one-day trips into the Orestimba led by the author. GavilanCE.com or (408) 852-2801.

Looking east from the top of Bear Mountain, you will see that the rugged and deeply corrugated topography so characteristic of Coe Park relaxes in the Orestimba Valley into a broad, gently rolling blue oak “savanna.” Names like Mustang Flat and Paradise Flat hint at a softening of the terrain.

The derivation of the word “Orestimba” itself is uncertain. “Ores” means “bear” in the Mutsun dialect spoken by the Ohlone people who lived in this area, but that is all historians know for sure.

The land that would become the Orestimba Wilderness was part of the acquisition of the Mustang-Gill Ranch by California State Parks in 1981. Central Valley interests opposed the purchase over concerns about the loss of private cattle ranchland and lost development possibilities, which reduced the overall size of the acquisition to 34,800 acres. The approval of Coe Park’s General Plan in 1985 excluded cattle from the park and designated the 22,000 acres of the Orestimba as wilderness.

I clearly remember the first time I saw this place. It was spring, so the grass was green and the creeks were running. Warm morning light dappled the forest floor through the porous canopy of blue oaks just beginning to leaf out. Larkspurs, shooting stars, purple owl’s clover, and lupine decorated the lush forest floor, but I was most moved by the surprisingly gentle and accessible terrain. At the source of the South Fork of Orestimba Creek, the steep chaparral-choked country began to give way to a landscape that reached out with open arms and promised a warm and comfortable passage. The contrast was striking. No more sweat-soaked, heart-pounding miles to travel. Instead, I walked comfortably through relaxed country that unfolded before me like a pastoral landscape painting.

Recently, I lured Barry Breckling, who was a ranger at Coe State Park for 30 years before retiring in 2007, out of his Sierra foothill home and back to the park for a return visit to the Orestimba with me. A passionate naturalist, Barry seems to know every shrub and hidden feature of this vast park. We entered at the Dowdy Ranch entrance off Highway 152 west of Pacheco Pass, the closest to the Orestimba. This entrance is generally closed to the public except on weekends, but as a uniformed park volunteer, I was able to get permission to enter through the locked gates at Bell’s Station.

We drove past the Orestimba Corral, a relic of the region’s historic cattle ranching days, along a road that follows the gentle descent of Orestimba Creek and the wilderness boundary. On the slopes that rise from the valley floor, gray pines, buckeye, and California juniper rose above interior goldenbush, buckbrush, and a host of other chaparral species.

As we rode past the confluence of Red Creek and the South Fork of Orestimba Creek, I remembered my campsite there on the last night of a backpack trip years ago. I was part of a group of park volunteers that had spent the weekend clearing coyote brush, buckbrush, and chamise from an overgrown Mt. Stakes Trail. Sunday evening, everyone else headed home while I stayed behind to backpack down the 10-mile length of Red Creek.

Born at the very north end of Coe Park, Red Creek is one of the three main streams that drain the Orestimba Wilderness. This is unlike the open terrain along Orestimba Creek: Hills rise steeply from the banks of Red Creek, cutting off any distant views. While eating dinner on the first night of my trip, I went to investigate a matted-down area I saw in the grass near my sleeping bag. The dismembered skeletal remains of a deer carcass were strewn all about, testament to a life-and-death drama that had taken place here not long before. The next day, farther down the trail, I found still more evidence of lion kills, and I started noticing many spots along the creek that looked like perfect ambush sites. In all my years of exploring every corner of Coe Park, I have never seen a mountain lion there. But I’m pretty sure that they have seen me.

Barry and I drove on, and he soon remarked that the hills showed almost no scars from the massive Lick Fire. In September 2007, a hunter’s debris fire on private property adjacent to the park escaped and burned 47,760 acres — more than half of Coe Park. I remember watching massive columns of smoke rise over the park from my Morgan Hill home. This area of the park had not burned in a half-century, and the fuel buildup, combined with the heat and rugged terrain, repelled every attempt to contain it. Finally, firefighters were forced to retreat to the road Barry and I were now on — a defensible position — and wait for the fire to come to them.

At the time, we had worried that the intensity of the fire would severely damage the landscape. But, in fact, the blaze left a mosaic pattern that proved to be an ecological benefit to the region. Some chaparral hillsides burned fiercely, leaving a barren moonscape; other areas burned cool beneath tree branches or completely avoided the flames. Coe Park volunteers later did a fire recovery study and found a robust springtime display of whispering bells, a wildflower not seen in the area for many decades. The only evidence of the burn that Barry and I saw on the slope up to County Line Road was a few black snags standing above a fully recovered landscape.

At the end of the road, we parked beneath the Rooster Comb, the most distinctive geologic feature of the Orestimba Wilderness. Here, the gentle landscape we had just crossed ended and rugged relief returned to view beneath the system of ridges and hills that cascade down from nearby Robison Mountain. The Rooster Comb, a forty-foot-high ribbon of radiolarian chert, rolled up and down along the crest of the ridge above us. This band of reddish brown rock was formed from an accumulation of countless protozoan skeletons that collected on the seafloor 90 to 120 million years ago. The powerful forces of shifting and colliding tectonic plates transported the rocks from hundreds of miles away, bent and folded the layers, turned them on end, and exposed them here in a striking way.

Barry and I stepped across the dry streambed of the South Fork of Orestimba Creek and into the Orestimba Wilderness. The trail rose toward the Rooster Comb through a spacious blue oak woodland. We paused beneath one oak covered with so many small wasp galls — as many as twenty to a leaf — that the blue-green foliage took on a reddish hue. Farther on, up at the base of the Rooster Comb’s sheer wall, it took us a while to find an old mine shaft we knew was there. Barry called it the “two-second” shaft and then tossed a rock down the dark vertical bore to make his point. Sure enough, one Mississippi, two Mississippi … whack!

There are a number of old mines in the Orestimba Wilderness, but as park historian Teddy Goodrich points out, “prospecting in the area was driven by market demand,” so what prospectors were looking for in any particular shaft depended somewhat on when it was dug. The predominant commercially valuable mineral in the area is cinnabar, but magnesite and manganese are other important minerals present in the Orestimba.

As we descended the far side of the Rooster Comb, Barry pointed to the dried tassels of seedpods on a California ash, a tree I had never seen in the park. We continued down through a thicket of hollyleaf cherry until we stood beneath the rising hulk of Robison Mountain. On the far side of the mountain and out of our view, Robison Creek, the third principal drainage of the Orestimba Wilderness, runs between Robison Mountain and Mount Stakes on its way to the South Fork of Orestimba Creek near the northeast corner of the wilderness.

We would not reach there this day, but I remember a hike up Robison Creek with Barry years ago to its junction with Pinto Creek, where the valley widens into another broad pastoral expanse so remarkable in these rugged hills. On that day, we ate lunch on a wide grassy bench set several feet above the valley floor. It was a beautiful setting shaded by huge gray pines. Until Barry pointed them out, I hadn’t noticed several shallow oval-shaped depressions — maybe 20 feet across — dug in the soil long ago by resident Native Americans. The Yokuts people dug them to increase the volume of their shelters, which were framed with willow and thatched with bunchgrasses and tule. After Barry brought them to my attention, this lovely spot seemed to vibrate with the spirits of the community that once dwelled here. It was strange to imagine such populated vitality in a place now so utterly remote.

The Orestimba is a wilderness in the fullest meaning of the word. As a longtime volunteer at Coe Park, I have visited the Orestimba Wilderness many times over the last 20 years. I have startled groups of tule elk, seen countless coyotes, bobcats, and golden eagles. In spring, when the hills are green and the creeks are running, I have crossed fields ablaze with shooting stars. I have watched the setting sun ignite the Rooster Comb, and a little later, I have lain down beneath a star show of stunning clarity. In most wilderness areas in the lower 48 states, there would probably be another camper a mile or two down the trail. Not here. In the Orestimba Wilderness, I’m not far from home, but the solitude is so complete, it’s almost unnerving.