Biologist Denise Cadman was in college when she first heard of the Laguna de Santa Rosa. Her water-skier boyfriend had a brainstorm: dam the seasonal wetland and turn it into a water-ski slalom course with jumps and platforms. Her boyfriend’s brother nixed that one fast when he reminded the pair that the Laguna was where the city dumped its sewage. Little did Cadman imagine she would one day be in charge of protecting and restoring the Laguna’s habitats, from farmlands to creeksides to marshes. And little did anyone in 1983 imagine that the public’s perception of the Laguna would shift from swampy dumping ground to natural treasure, or that restoring the Laguna would feature in the city of Santa Rosa’s wastewater treatment program.

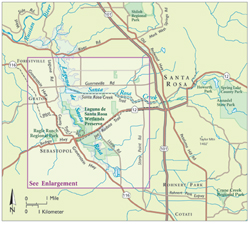

The name, Laguna, refers both to an actual waterway—a slow and sinuous 14-mile ribbon that is the largest and southernmost tributary of the Russian River, which it joins at Forestville—and, more broadly, to the 7,500-acre floodplain that spreads from Santa Rosa east to Sebastopol and from Cotati north to Forestville. This patchwork of open water, riparian forest, seasonal wetlands, grassland, and vernal pools seems in summer to be a host of separate, unrelated locations; but in winter, water connects it all to form the largest freshwater wetland complex on the North Coast. The Mexicans who named the place obviously saw it in winter, when extensive swaths of grassland and even the massive valley oaks stood under several feet of water. Nowadays, the eastern two-thirds of the floodplain does little to hold or slow down rainwater—like most heavily populated areas, it’s all about pavement and concrete storm-water channels. The real work of flood control is done by the remaining one-third of the Laguna that is more or less intact. Its floodplain can store up to 80,000 acre-feet of storm water, enough to lower Russian River flood levels by 14 feet. To hydrologists it may be just an incidental bonus that the Laguna also provides fabulously rich wildlife habitat.

On a sunny Saturday in spring 2005, more than 50 people showed up for a rare guided walk around normally off-limits Delta Pond, west of Santa Rosa. The pond itself was not the draw—the mile-long man-made pond holds 1.5 billion gallons of fully treated discharge from the sewage plant, which is released gradually into the Laguna in the winter or, in other seasons, shunted via pipeline to city-owned farms and parks for irrigation. Its depth and steep banks are deemed a liability issue by the city—hence the restriction on public access. But the wide trail around the pond is high enough above the surrounding Laguna to provide spectacular views, including, at the west end, the only clear vantage point into the canopies of huge valley oaks that house a thriving rookery of great blue herons, great egrets, and double-crested cormorants.

- Denise Cadman (foreground) leads much of the restorationwork in the Laguna. Here, she and a crew of volunteers are removinginvasive purple loosestrife. Photo by Don Jackson, www.donjackson.com.

Cadman, who is the City of Santa Rosa’s natural resource specialist and a board member at the Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation, has been observing the rookery since 1995, when there were just two nests in these big trees. In 2005, there were almost 150 nests. When the herons and cormorants arrive in late January, Cadman photographs the twiggy piles in the bare branches to help her locate the nests later when the trees have leafed out. In late spring the canopy revealed only the nests at the upper edges. Heron chicks big enough to be gangly but still covered in fuzzy down peered over the rims of twigs. The filmy breeding plumage of great egrets billowed around parents standing in their nests, illustrating the appeal that drove them to near-extinction for the sake of hat decorations a century ago. The cormorants, which nest at the top of the canopy, seem unlikely neighbors for herons and egrets. Their webbed feet make gathering nest materials a difficult proposition—unless they steal sticks from nearby nests, which makes the arrangement handy as all get-out, at least for the cormorants. There is safety in numbers for the whole rookery, with many parents ready to sound the alarm when they spot a hawk or other predator. Even when peace prevails, the constant clacking and chirring identifies the rookery as a large and lively community.

Cadman tracks the progress of each nesting pair throughout the breeding season for Audubon Canyon Ranch, spending a full day at Delta Pond twice a month. “How often does anyone get to sit and watch a bird for eight hours?” she asks happily. Other birds could be seen coasting above the Laguna or cruising the shallow water below—ospreys, white-tailed kites, black-necked stilts, shovelers, a mallard with 11 ducklings. An important stopover on the Pacific Flyway, the Laguna shelters a wide array of birds at every season. Timber Hill, a wooded bump just west of Delta Pond, was the home of legendary birder Gordon Bolander, who set a high standard for yard lists (birder lingo for number of species seen in one’s own yard) with 229 species over the course of his 26 years there. The Laguna also hosts a relative abundance of vernal pools, where hardpan soils create seasonal wetlands home to many rare plant species, including Sebastopol meadowfoam and Burke’s goldfield, which grow nowhere else.

Of course, even this abundance barely touches the condition of the Laguna just 200 years ago. All the grand descriptions of pre-European California—streams packed solid with returning steelhead, thousands of pronghorn undulating across the grasslands, clouds of migrating ducks so dense they blocked out the sun—all this occurred in spades at the Laguna de Santa Rosa. The North Bay also had some of the densest populations of people in the Americas, with a history of continuous human habitation going back at least 11,000 years, according to archaeological evidence.

The degradation of the Laguna came so fast that newcomers hardly noticed what we had before it almost entirely disappeared. The first Mexican land grant here was in 1833, but development didn’t gain much momentum until the Gold Rush created a boom economy. In the late 1870s, draining and channelization of the Laguna provided solid ground for the railroad. Settlers cleared the 150-foot-tall valley oaks that anchored the riparian woodlands in order to plant hops, grain, and orchards. Commercial hunters supplied the burgeoning population of San Francisco (in 1892, one hunter recorded killing 6,200 ducks for market). Farmers pumped increasing volumes of water from the Laguna in summer. The 20th century brought apple canneries and factory-size dairies to Sebastopol; they lined up along the Laguna with their waste discharge pipes out the back. As Cadman puts it, “we literally turned our back on the Laguna.”

While people began recognizing the problems with dumping sewage into the Laguna by the late 1800s, it took polio and diphtheria outbreaks in 1943 for the channel to be closed to swimming, and it wasn’t until 1978 that Sebastopol closed its sewage facilities in the Laguna. Residential development began to boom in the 1950s, and the busy work of the Army Corps of Engineers in the following decade drained more acreage. Concrete channels moved storm water through Santa Rosa quickly, but also caused erosion and sediment buildup in the Laguna and more flooding of the Russian River. Every new building or paved street added to the runoff and subtracted from the water-holding sponge that had made up the Laguna, until by 1990 only 8 percent of the Laguna’s former riparian areas remained.

While much has been lost, there has recently been a very snappy about-face. A small group of local residents began the Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation in 1989; it has become a guiding force for the Laguna’s future, and the major educator about the Laguna. Also in the late 1980s, Santa Rosa’s Reclamation Department, in charge of sewage and storm water for Cotati, Rohnert Park, Sebastopol, and Santa Rosa, began to look at wetland restoration and creation as an inexpensive and environmentally sound way to deal with its daily average of 20 million gallons of treated wastewater. The department built Kelly Demonstration Wetlands and brought Denise Cadman on board to monitor the experiment; her steady behind-the-scenes expansion of the city’s restoration activities has had an enormous cumulative impact. The treatment plant in west Santa Rosa pumps half its finished outflow 43 miles north to the Geysers Reclamation Project, where the added steam at the hot springs generates electricity for 80,000 homes. The remaining 5 million gallons per day travels from the holding ponds to irrigate 6,000 acres of parks, golf courses, dairies, and four city-owned farms. The city farms are under conservation easements, with wildlife areas set aside; creek, hedgerow, and woodland restoration projects are in progress. Creeks replanted with willow trace dense ribbons of green, and patches of young valley oaks thrive in low spots, bringing back the riparian woodland that led settlers to call these trees mush oaks‚ because of their tolerance for winter inundation.

Though public access to the Laguna is limited, work has begun on new trails that will greatly expand hiking and birding opportunities, mainly using restored parts of the city-owned farms. Trails open now include two popular east-west traverses between Santa Rosa and Sebastopol. Santa Rosa Creek Trail is a raised gravel road under the shade of old oaks, with views of dairy pastures, vineyards, and the creek. The Joe Rodota Trail’s paved surface makes it popular with bicyclists, rollerbladers, and parents with strollers, as well as with pedestrians; it includes a wide wooden bridge across the Laguna waterway.

At the Laguna de Santa Rosa Wetlands Preserve in Sebastopol, one of the few public access points to the waterway itself, hundreds of volunteers have planted willows and Oregon ash in the wettest areas, oaks and California black walnuts a few feet higher, and once-plentiful shrubs like elderberry and wild rose that provide wildlife with food and shelter. In just the past seven years, the preserve has been transformed from dumping ground to home for river otters, waterbirds, and 18 species of dragonflies. Some plantings, especially those boosted by self-propagating poison oak and Himalayan blackberry, have already reached the tangled, impenetrable state of prime bird habitat, though several miles of looping trails keep it accessible to human visitors.

The foundation offers regularly scheduled docent-led walks into wilder parts of the Laguna not often open to the public. For those who want to get more deeply involved, there are the Laguna Keepers and the Learning Laguna school program.

Laguna Keepers spend one Saturday a month from September to April (bird-nesting season is time out) doing restoration activities like gathering and planting acorns in parts of the Laguna not otherwise accessible. Laguna Foundation docents are trained to guide hikes and lead the Learning Laguna two-part educational program for elementary school students.

Friends of the Laguna are confronting two challenges to the wetland’s integrity, one botanical and one human in origin. The botanical menace is an invasive water primrose, a species of Ludwigia. Four years ago it appeared as small clusters in several locations. Now it covers nearly 300 acres in a solid vegetative mass that extends four to five feet out of the water and plunges to an equal depth, choking out every other plant, preventing waterfowl from landing, and sheltering the particular mosquito that carries West Nile virus. An aggressive campaign of aquatic herbicide, followed by heavy equipment to remove the dead plants, was carried out this summer on Santa Rosa and Rohnert Park infestations.

The other challenge remains encroaching development. In Sebastopol, a proposed 140-unit housing project called Laguna Vista has remained mired in controversies over traffic and environmental concerns for years. The conflict boiled over in spring 2005 when the endangered Sebastopol meadowfoam was found on the site. The state’s determination that the wildflower had been illegally transplanted to the site only intensified the debate, especially when state biologists refused to give reasons for the decision on the basis that the information might encourage copycats. The development still faces other hurdles, including a pending lawsuit brought by a group of neighbors against the city of Sebastopol for violating its own open space ordinance.

Not far away, the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, Coast Miwok descendants of the original Laguna dwellers, have proposed a casino and resort complex on part of a 271-acre site off Highway 101 near Rohnert Park. In mid-August, the tribe announced that it had shifted its proposed development out of the Laguna’s 100-year floodplain and into the designated urban growth boundary around Rohnert Park.

Overall, the future of the Laguna looks like collaboration rather than combat. The Laguna Foundation is in the last half of a two-year restoration planning project funded by a hefty Coastal Conservancy grant. In addition, a Sonoma County quarter-cent sales tax goes to the Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District, which cultivates relationships with Laguna landowners, letting them know about options for selling development rights, putting restrictions in deeds, or selling outright to the city. The district is planning a series of connector trails to provide greater public access to the Laguna. And to provide a central focus for the Laguna’s diverse ecosystems, the Laguna Foundation has leased buildings on the city-owned Stone Farm to eventually house the Laguna Learning Center, which will focus on the ecology of the Laguna, and also include Native American cultural exhibits and demonstrations.

In an unprecedented action of good will, the Graton Rancheria Indians have stepped up with a $100,000 donation toward the learning center, all the more generous because the money comes from the tribe’s loan for its as yet unbuilt casino. Environmental restoration and education—that’s where we’re going to put our profits,” says tribal chairman Greg Sarris. “We’re coming back as caretakers of the land and water,” he adds, “indigenous people and people who’ve come here, working together—this is a model for the world. We’re happy and fortunate that we’re still around to do this.” With so many people recognizing the jewel that is Laguna de Santa Rosa, and with its robust mix of stakeholders, the area could become a blueprint for managing complex, interconnected environments for the benefit of all—birds, animals, and humans alike

Getting There

- Ben Pease, www.peasepress.com

The Joe Rodota Trail: In Santa Rosa, start at the western end of Sebastopol Road. From Sebastopol, the trailhead is just south of Powerhouse Brewing Company on Petaluma Avenue (Highway 116 north).

Santa Rosa Creek Trail: From Willowside Road (between Hall Road and Guerneville Road) the trail goes both directions.

Laguna de Santa Rosa Wetlands Preserve: Take Highway 12 to Sebastopol, turn right at Morris Street (the first stoplight), then right at the Community Center. Parking and trailheads are behind the Youth Annex. Be sure to check on the cliff swallow colony on the back wall of the Youth Annex during spring and summer.

- Ben Pease, www.peasepress.com

Check the Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation website for information about docent-led hikes, Laguna Keepers, or volunteering with Learning Laguna: www.lagunadesantarosa.org.

.jpg)

-300x225.jpg)

-300x202.jpg)