The Pinnacles formation of the Gabilan Mountains is hereby charged with abandonment. Once a volcano bound it in welded bliss with a twin sister in Los Angeles County. Then the Pinnacles portion hopped a geologic freight train moving north and never looked back.

The structure of their initial relationship was forged when rock and ash spewed forth in violent explosions between 23 and 22 million years ago, building a heap like Mount Lassen.

The vulcanism was caused, as it commonly is on the Pacific Rim, by the clash and heave of tectonic plates. Off the coast of present-day Los Angeles, a gap behind the heavy and old Farallon Plate, which was being squeezed between the North American and Pacific plates, allowed magma to well up from the earth’s mantle and erupt.

In this area where the three plates met, both subduction (when one plate over-rides another) and lateral shifting (where one plate grinds past another) were taking place. In the process, fault systems were created, including a major crack we now call the San Andreas Fault. Movement on the San Andreas ripped the volcanic mass of the old Pinnacles volcano in half, and the coastal side began to slide north.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Getting There

For the east side, take Highway 101 and Highway 25 south through Hollister, continue 30 miles, then right on Highway 146. Turn left into the campground. For the west side, take 101 south to Soledad, then 146 east 14 miles. Find out more at the Pinnacles website.

The halves did not turn out to be a good match for each other, anyway. No flock of tourists now travels to “ooh” and “ahh” over Neenach, the name of that stay-at-home, southern portion of the old volcano. Meanwhile, the entity that shifted 200 miles north to lodge near Salinas and Hollister now enjoys fame as Pinnacles National Monument. It sees 170,000 visitors per year despite being remote from large population centers. This park amply justifies the 130-mile drive from the San Francisco Bay Area.

As it crept north at a modest pace of a few centimeters per year, the Pinnacles underwent a major makeover.

Down south, Neenach stayed exposed to air and eroded into a set of low hills. But the Pinnacles rode upon a geologic freight car of a “graben,” a fault block that sank and was covered up by sediments, and was thus saved from millennia of erosion.

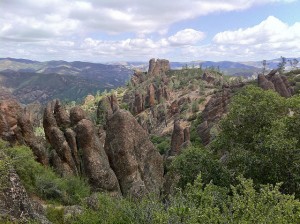

Eventually, that graben with its cargo of volcanic rock was uplifted once more, cleansed of sediment, then sculpted by wind, rain, and frost to stand revealed as a natural theme park full of priapic spires, jagged cliffs, and boulder-choked canyons.

At Pinnacles, geologic action has bestowed a volcanic mass seven miles long and 2.5 miles wide, ranging from 824 feet to 3,304 feet in elevation. This giant, corrugated slab also dives below ground; it’s more than a mile thick, in total, constituting more than three cubic miles of volcanic ejecta.

That last word is key. The Pinnacles volcano did not spread in sheets of black lava like a Hawaiian shield volcano, but instead coughed up a mix of hot chunks and fine particles that set like concrete as it all accumulated and cooled. This material hardened further with ongoing exposure to air and moisture. The net result is a thick, hard rock called breccia that covers 80 percent of the monument.

This breccia generally presents a pinkish-brown cast, due to the presence of oxidized particles of iron. After primitive life forms took a lichen to these cliffs, shades of yellow, green, red, and brown were added to the palette. Some 90 species of lichen now paint the rocks and assist erosion as they gently digest their home. Dabs and streaks of white guano accent the artwork, courtesy of the feathered friends of the Pinnacles, including California condors, prairie falcons, great horned owls, golden eagles, and peregrine falcons — all drawn to the protected aeries of these peaks, with their flight-boosting updrafts.

Each species has its own modern survival story. The most epic is that of the condor. With a wingspan that approaches ten feet, these “thunderbirds” of Native American mythology flew all over the Pacific Coast and some distance inland in the early 1800s, but only 22 individuals were left alive by 1982. A massive and expensive effort was launched to halt their dive into extinction. This program had its pratfalls, but the upshot is that 366 condors now exist, 186 of them in the wild, landing on beaches to scavenge dead sea lions, soaring over inland canyons to search out deceased cattle and deer. They have begun to mate in and around two of their ancestral homes to the south of the Bay Area: Pinnacles and Big Sur.

Park personnel experienced a frisson of excitement when a Big Sur and a Pinnacles bird began to court in late 2009, then mated. Now, their nest was nothing special–just a classic, unfurnished “condorminium.” Condors commonly select a rock niche with gravel on the floor, then plop a four- or five-inch-long egg right on the dirt. But a fluffy chick did hatch in spring 2010, the first born in the wild at Pinnacles in more than a century. Enthusiasm diminished when researchers found the chick and its dad bore high levels of lead in their blood. They had to be captured and brought to the Los Angeles Zoo for treatment.

A ban on use of lead ammunition–which contaminates the carrion eaten by these scavengers–has been in place for years in the areas that condors cruise. Yet lead bullets and shot remain the most likely cause of this ongoing problem, according to chemical tests done at UC Santa Cruz. Because a condor’s daily cruise can extend up to 150 miles, the precise locations of these contaminations are difficult to pinpoint.

In many other respects, the Pinnacles seem pristine. Set aside by Teddy Roosevelt in 1908, during the same month he preserved Muir Woods and the Grand Canyon, this monument is among the nation’s oldest.

“Because it’s been protected so long, the Pinnacles are an oasis for many different native plants and animals,” says Carl Brenner, the monument’s chief of interpretation. He’s been here 12 years, and has no plans to depart. “There’s rock zones (with sparse vegetation), oak woodlands, streams, five types of chaparral communities, plenty of ecological niches for all sorts of creatures. There’s so much variation. Every season has something special to offer.”

The monument grew in a series of bounds to its current size of 26,245 acres. Designated wilderness accounts for 61 percent of that total. A century of protection, along with distance from urban influence, has kept native plant communities intact and exotic species at bay. Most streams trickling through the park have their headwaters here too, so riparian zones are fairly healthy.

The biggest threat to native biota was an invasion by feral pigs in the 1960s. These “hooved locusts” descend from hogs used as traveling larders by Spanish explorers, as well as escaped domestic pigs of the pioneer families, and European boars imported to Monterey County as game for hunters. This mix produced fecund hybrids eager to chomp down acorns, root up bulbs, and munch on insects, reptiles, and anything else under their snouts. The burgeoning problem was stanched by building 24 miles of pig-proof fence. Completed in 2003, the barrier must be patrolled to ensure its integrity. More miles of such fencing are planned.

If they could breathe out a sigh of relief–not simply their pleasing fragrance–the 500 species of native plants at the Pinnacles would probably do so.

Most of the hillside acreage, 82 percent, is furred with various types of chaparral, with chamise (sometimes called greasewood) and ceanothus dominating. But there’s a surprising number of trees, especially gray pine (whose roots can writhe more than 150 feet in quest of moisture), buckeye, cottonwood, sycamore, and blue, valley, and coast live oak.

They provide welcome shade to visitors daring to approach in July and August, when daytime temperatures often soar above 90 or even 100 degrees. (The swimming pool at the east side campground also offers relief.) However, most visitors choose to arrive in fall for hiking and climbing, and in spring to view abundant wildflower displays.

“People always ask when I think the peak of the wildflower season will be,” says the park’s wildlife biologist, Paul Johnson. “I answer with another question, ‘What do you want to see?’ Some native plants bloom at the end of winter, others in early fall. For a weather-typical year, March is best for annuals, April for perennials. February through May is a pretty good bet.”

My most recent visit occurred this past June, following a spring sprinkled by late, cool rains. Vistas along the park’s 30 miles of trail were brightened by purple puffs of coyote mint, the yellow trumpets of sticky monkeyflower, mauve quilts of elegant clarkia, spikes of wooly bluecurls, pale chalices of butterfly mariposa lily, and the green-gold-white coontails of chamise blossoms.

Just as the rugged crags draw birds of prey, abundant native plants nurture an abundance of insect life–which attracts yet more birds. Bird watchers, too. Birders can see the expected (like acorn woodpeckers, California quail, canyon wrens, scrub jays, and wrentits) but also glimpse more exotic fare like California thrashers and Lawrence’s goldfinches.

An inventory in the 1990s counted some 400 bee species here, the world’s highest known diversity per square mile. There are also 69 types of butterflies, 40 species of dragonflies and damselflies, and an estimated 1,000 kinds of moths.

Consequently, this park provides a happy hunting ground for 14 different bat species. Pinnacles both spreads a smorgasbord and offers superior habitat. The most famed caves are the (long) Bear Gulch Cave on the east side, and the (shorter) Balconies Cave to the west. These talus caves were assembled when eroded blocks of stone (talus) tumbled into narrow creek canyons, blocking out light and creating narrow, twisting passageways that invite exploration.

But this being a national monument, protection of the resource takes priority over satisfaction of human curiosity. Bear Gulch Cave is closed to visitors mid-May through mid-July, when maternal colonies of Townsend’s big-eared bats pup their young, and again in winter when they hibernate in clusters. Balconies Cave, which has fewer bats, is closed only when the ephemeral creek on the cave’s floor goes into flood.

Bats flit through the night, resembling balled-up rags of black silk flung by unseen hands. First to emerge are the tiny canyon bats (aka western pipistrelles, about two inches long), then come larger pallid bats that hunt crickets and scorpions. Bats use chirps to echolocate prey (like a submarine’s sonar). The western mastiff bats–three times larger than a canyon bat–can produce chirps low enough for us to hear.

We may hear only the mastiffs, but Johnson says the moths that bats hunt can likely hear them all, and respond.

“Studies have shown that many moths, if hit by a bat’s echolocation, simply fold their wings and drop,” Johnson says. “But, that’s nothing! Some moths are able to jam that signal, to send a matching vibration back out to confuse the bat.”

The nocturnal charms of the Pinnacles, as well as the heinous heat of some afternoons, have prompted park managers to allow hiking 24 hours a day, including a new program of guided night hikes that will be offered summer through fall. Participants can see those flitting bats, bioluminescent critters like glow worms, and reflection of the stars upon the still waters of Bear Gulch Reservoir. This is the park’s sole lake, formed by a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) stonework dam during the Great Depression. Views of stars directly overhead, by the way, are impressive, since rural isolation shields Pinnacles from urban light pollution.

By day, visitors can enjoy short, intricate loops such as the Moses Spring Trail, harder hikes like the seven miles of the North Wilderness Trail, the six-mile path out to South Chalone Peak, or strenuous jaunts like the High Peaks Trail, which traverses the park’s crest using steps carved into stone and steel railings installed by those same CCC workers.

For the truly adventurous, Pinnacles offers multiple rock-climbing routes. Chunks of rhyolite, projecting from the breccia, provide multiple hand- and footholds for good “face” climbing.

“It’s very beautiful at Pinnacles,” says Royal Robbins, a veteran lead climber from Yosemite’s “Big Wall” heyday. For Robbins and his climbing pals in the 1960s and ’70s, Pinnacles offered a warm place for ascents in spring and fall. “That rock can be exciting, the caves are strange and interesting, and I’ve had good wildlife sightings. The fact that no road crosses the park helps it stay wild. Once you get atop those formations, the park has a wonderful sense of isolation.”

Although Robbins cites rattlesnakes among his sightings, the Northern Pacific rattlers that live here are a relatively docile breed.

Besides, as Brenner says, the major threat to visitors here is not bats, bugs, or snakes, but inattention. “Our number-one injury is twisted ankles. People get so excited about what they see all around them, they often stop watching where they put their feet.”

-300x201.jpg)

-300x221.jpg)