When I started visiting Point Reyes in the 1970s, the landscape from Limantour Beach up to the crest of Inverness Ridge had a special appeal. I had spent my early childhood in the New England countryside in the 1940s, so vestiges of the pre-Seashore ranching days made me nostalgic–homestead sites, dammed lakes, fence lines, timothy hay growing in old fields. On the other hand, watching the wild ecosystem come back, with its brush rabbits, jackrabbits, quail, hawks, and bobcats, was endlessly fascinating.

Yet I wasn’t too clear about what that wild ecosystem was. I knew that north central Point Reyes supported a forest of bishop pine, Pinus muricata, a species confined to areas of relatively dry and nutrient-poor soils along the Pacific coast. Granitic bedrock and proximity to the ocean (where the trees benefit from fog drip) make the Limantour area a good place for it. Like its close relative, Monterey pine, it is a closed cone species, the firmly attached asymmetrical cones remaining on the branches instead of opening to release their seeds and then falling off as with most pine species. Named for San Luis Obispo (“obispo” being Spanish for “bishop”), where it was first identified, bishop pine now occurs in scattered stands from Santa Barbara to Humboldt County, with an isolated population in Baja California. Fossils show that its ancestors were more widespread during drier times over the past two to five million years.

Hiking the Limantour area back in the 1970s, I saw plenty of bishop pines. Yet the pines on the crest and west slopes of Inverness Ridge seemed a little too peripheral and vestigial to be considered a “bishop pine ecosystem.” Point Reyes’ main bishop pine forest occurred on the ridge’s east slopes, down to Tomales Bay. I knew places along the Inverness Ridge Trail where bishop pines were large for a species that seldom grows over 50 feet tall or lives more than a century, but few young pines grew in the understory of huckleberry and other shrubs. Although hot weather or gray squirrels can open some cones, those factors don’t release enough seeds to regenerate a pine forest, and bishop pine seedlings compete poorly with other tree species in their parents’ shade. Saplings of hardwoods like bay laurel, wax myrtle, madrone, and oak mainly grew there, and the largest pines seemed senescent.

There were places on the ridge’s west slopes where small pines predominated, but these spots were shallow-soiled granitic out-crops and the little pines were dwarfs, older than they looked, growing where few other woody plants could survive. On deeper-soiled sites, Douglas fir saplings poked up here and there among grass and brush. Although the landscape changed little from year to year, the overall plant succession seemed headed toward the mixed hardwood and Douglas fir forest that grows on the sandstone and shale bedrock to the south in Point Reyes.

Then came the wildfire of October 1995, which consumed the vegetation from Mount Vision west to Limantour Beach with astounding thoroughness, partly because the pines burned so readily. The fire burned more patchily in the Douglas fir and hardwood forest south of Kelham Beach. Standing on a headland a few weeks after the fire and seeing almost nothing but blackened earth in every direction, I felt less inclined than before to take plants for granted. And the astounding speed with which the plants reclaimed the area over the next few years made me take them even less for granted. They began to seem less vegetative and more dynamic–almost animated. Bracken fern and coyote bush sprouted from charred bases days after the fire. Grasses and forbs like trefoil, lupine, clover, and rush-rose covered the soil by the summer. Shrubs and vines–blueblossom ceanothus, huckleberry, manroot, blackberry–shaded out many of the herbs by the summer after that. Some patches of blueblossom grew six feet tall in that time.

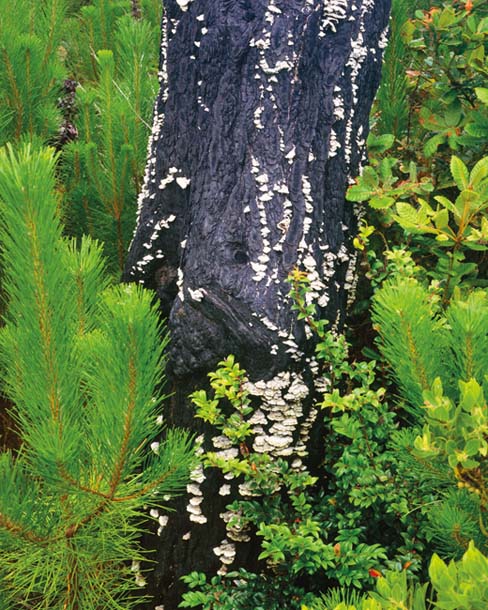

No plant species in the post-fire Limantour area seemed more dynamic, however, than Pinus muricata. The fire killed almost all the existing pines in the burn area. Yet its heat freed countless seeds–which can stay viable for decades within their sealed cones–by melting the resin of the cones, thus opening the scales. Fiery updrafts sent the winged seeds showering onto the westward slopes and headlands, including many places where pines had not occurred. Pine seedlings started appearing a few months after the fire and a year later formed large, irregular patches in sites where grass, brush, or Douglas fir had seemed the permanent vegetation.

Those seedlings seemed different from the bishop pines I’d known before. The pre-fire trees had a lot of character, both the picturesque, umbrella-shaped large specimens and the gnarled, persistent little ones. But they were a bit drab–their needles plain green; their trunks, branches and cones grayish. The post-fire bishop pines had an electric quality, as though some plugged-in current was emanating from them, making bark and needles glow.

A phenomenon in the soil may have contributed to this impression of enhanced vitality. Mycologists found that the fire stimulated a population explosion of fungi that live symbiotically on the roots of young bishop pines, which helps them absorb mineral nutrients in return for photosynthesis-produced food. Uncommon before the fire (when other fungi species performed this function for the mature trees), the young fungi–Rhizopogon and Tuber–grew abundantly from spores that probably had been resting in the soil for decades.

Looking east from Limantour Beach toward Inverness Ridge in 1997, I saw few of the farmland vestiges that had made me nostalgic before the fire. The burned landscape reminded me more of Yellowstone National Park. The headlands and slopes now had a similar shaggy look, like a landscape for elk rather than cattle, and in 1998 the park service did indeed introduce some tule elk here from the Tomales Point preserve.

Although flames temporarily decimated vulnerable species like the mountain beaver (not a beaver but a uniquely primitive rodent species with a race endemic to Point Reyes), the post-fire landscape seemed to attract and stimulate wildlife. Butterflies and other insects thronged the burned area even before the wildflowers bloomed, as though anticipating the feast to come. One insect species, a small black moth, proved new to science. Soon after the fire, I had my first and only sighting of a golden eagle–listed as rare at Point Reyes–at the park. Near Limantour I saw the only long-tailed weasel I’ve ever encountered in the park, although that may just have been due to the enhanced visibility post-fire. Meadow voles underwent one of their periodic population explosions, probably encouraged by the wealth of leguminous forbs.

There was no doubt after the Vision Fire that the Limantour area is a bishop pine ecosystem, just as there was no doubt after its 1987 fires that most of Yellowstone is a lodgepole pine ecosystem, also dependent on fire for renewal. I understood now how Pinus muricata‘s ancestor dominated a prehistoric landscape that included mammoths, sabertooths, and ground sloths as well as the surviving elk, deer, and mountain lions.

As the last ranching era vestiges have vanished, roads revegetated, dammed lakes and hay fields reverted to marshes and riparian woodland, I’ve sometimes missed my pre-fire nostalgia, but not that much. Bishop pine forest seems right for the place, although the wildfire on which it depends for renewal can be catastrophic. Still, whether started by an illegal campfire like the Vision Fire or by more natural factors, wildfires are inevitable, like earthquakes. We have to adapt to nature’s perils in the end, like all the other organisms.

The thousands of teenaged bishop pines now growing from Limantour Beach up to the Inverness Ridge Trail are vivid reminders of that fact, although the landscape doesn’t look quite as shaggy now as it did in 1997. In fact, some of it resembles a 1950s Weyerhauser tree farm ad, as the carpet of even-aged pines gives the slopes an almost industrial look. Some hikers find the close-growing young forest a bit claustrophobic and monotonous compared to the sweeping panoramas that the Bucklin and Drakes View trails offered before the fire. But time will open the forest as weaker trees die, and diversity will increase as young ferns, shrubs, and hardwoods creep into the understory, exploiting patches of sunlight that already penetrate the canopy.

Above, where their needles endlessly sing in the wind, the little pines’ two-foot-long, silver and amber terminal shoots still seem to glow from within. Female cones in various stages of development–bright green new ones, year old orange ones, weathered gray ones–ring the trunks and branches, patiently awaiting the next wildfire.

“Crowning Glories” was produced in collaboration with: Point Reyes National Seashore Association (PRNSA) is the primary nonprofit partner of the National Park Service at Point Reyes. PRNSA mobilizes community support for resource preservation projects within the park and provides environmental education programs that help people explore, discover, and connect with the natural world (ptreyes.org). National Park Service/Point Reyes National Seashore manages and provides public access to 90,000 acres of national park lands on and around the Point Reyes peninsula (nps.gov/pore). Funding for “Crowning Glories” was provided by the Point Reyes National Seashore Association and the JiJi Foundation, which supports conservation, research, and science education on environmental issues in California and Baja California.