Travel along Richmond Parkway and you’ll witness a parade of progress and decay, nature and commerce. Evidence of industry past and present shares fence lines with blighted lots, tract housing, new developments–and plenty of open space. To the west are marshland, shoreline, and San Francisco Bay. To the east is urban North Richmond. Here in the space in between, residents of a working-class subdivision called Parchester Village fought for decades to keep a neighboring marsh undeveloped.

They succeeded, and now tiny Breuner Marsh has evolved into one of the East Bay’s highest-profile shoreline restoration projects. It’s also shaping up to be one of the region’s pioneering efforts in sea level-rise planning, featuring a tidal marsh projected to withstand a waterline five feet higher than today’s.

The half-century battle for Breuner Marsh enters its final stage next year. In late summer or early fall 2013, the East Bay Regional Park District, which closed escrow on the land in 2011, begins the two-year process of restoring public use and near-optimal ecological function. After withstanding proposals to turn it into a small airport, a business park, a transit village, and multiple housing developments over the course of 40 years, the marsh will be not only protected but also rehabilitated.

Today the site waits in a sort of suspended animation. The tides still come in and out, the shorebirds still feast along the mudflats, and the native grasses still fight for space among invasive weeds. But soon this quiet backwater will be reconfigured to fulfill its potential as a recreational destination and a home for native wildlife.

“That area of the north Richmond shoreline is particularly valuable habitat,” says Nancy Wenninger, who, as assistant general manager of the park district’s land division, helped shepherd the acquisition. “It’s an important wildlife corridor. The upland area, the marsh area, and even the submerged area are all part of a very important mosaic of habitat. It’s a beautiful jewel on the Richmond shoreline.”

Indeed, the park district saw so much value here that it resorted to acquiring the land through eminent domain, an often contentious tactic it prefers to avoid.

-

Upland habitat at Breuner Marsh has been largely colonized by invasive species, but wildlife like this great blue heron can still be found here. Photo by Sally Rae Kimmel.

But if you really want to learn how big a deal the project is, the person to ask is park district board member Whitney Dotson, elected to his post in 2008 in part due to his efforts to protect the 218-acre parcel as open space.

“It’s a slow process to make these things happen, but I’m very much satisfied,” he says. “The big step is that the Breuner Marsh area is now saved. It’s just rewarding to see the public winning this battle.”

Dotson was only five years old when he moved with his family to Parchester Village in 1950. His father, the Reverend Richard Daniel Dotson, had joined about 20 other black ministers to work with sympathetic landowner Fred Parr on a master-planned community for African Americans.

Many of the new residents, including Dotson’s own family, had moved to Richmond from rural Louisiana. There they had been accustomed to wide open spaces, a luxury not afforded in industrialized Richmond.

The ministers agreed to recruit parishioners to buy homes in Parchester on one condition: The existing coastal areas to the north, south, and, perhaps most importantly, west–where the marsh is located–would remain undeveloped. “That fit right into the buffer zone that they were used to in rural Louisiana,” Dotson says. Parchester Village would be their sanctuary.

But by the early 1970s, development was exerting unrelenting pressure on the adjacent open space, which until then had been used primarily for cattle and sheep grazing. Despite his promise, Parr sold the marshland to Gerald Breuner (whose family owned the erstwhile Breuners furniture store chain). An aviation enthusiast, Breuner continued filling the site in hopes of building a small airport. Those plans were ultimately sunk by neighborhood opposition, but commercial development, pollution, and industry encroached on the community from the south and east.

Yet there was also good news: the park district’s purchase of Point Pinole Regional Shoreline, immediately to the north, which Dotson’s father helped secure in the early 1970s. A generation later, the original open-space agreement struck with Parr, and the impetus behind it–an appreciation of quiet land and the quality of life it can provide–fueled the efforts of Dotson and his neighbors to win the same protection for Breuner Marsh.

-

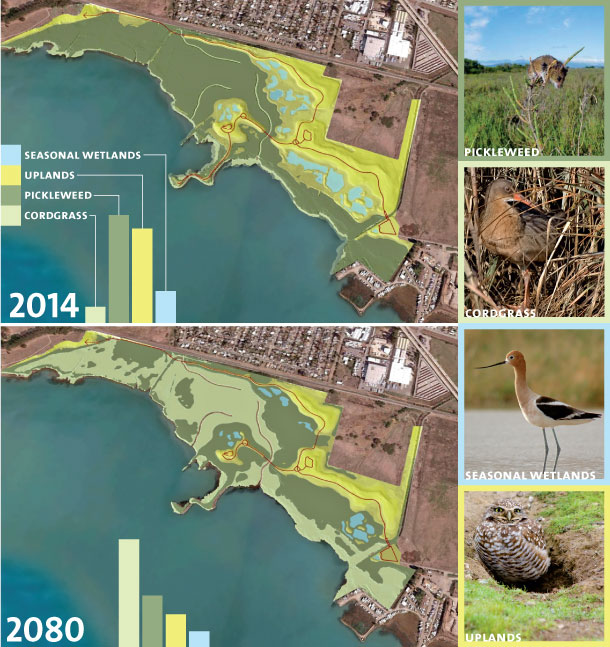

Breuner Marsh will change as sea level rises, but it should remain a healthy marsh. On top is the marsh just after restoration, when uplands and pickleweed will dominate, with plenty of salt marsh harvest mouse habitat. On the bottom, after 66 years and several feet of sea level rise, cordgrass will be the primary habitat, friendly to endangered California clapper rails but less so for the harvest mice. Credit: Satellite imagery: Google Earth. Map renderings and data: EBRPD. Habitat images (from upper left): U.S. Department of Interior, Ingrid Taylar (Creative Commons), Sfitzgerald86 (Creative Commons), Ken-ichi Ueda (Creative Commons)

Though this marsh is now finally protected, it’s not healthy–yet. If you view Breuner Marsh from above, you’ll notice it’s nearly devoid of the sinewy channels and burnt-amber hue of a pickleweed tidal marsh. It’s easy to spot the difference between Breuner and the two other marshes ringing Point Pinole: Giant and Whittell. That’s because, by and large, Breuner Marsh is no longer a marsh at all.

The original wetland was filled with excavated dirt, concrete, and construction debris from the 1940s through the 1980s. Disruption by off-road vehicles, scraping, and grading continued for another decade. Today the fill ranges in depth from as little as a foot to 12 feet near the entrance, and even higher in a pair of debris piles–unnatural, weed-choked lumps on the landscape. Daily tides don’t make it far inland anymore, so tidal wetland–and the habitat available to shorebirds at high tide–has shrunk to a sliver running along the Bay. Through decades of gradual infill, the marsh’s original size of about 60 acres has been reduced to 25, and the shoreline extended by hundreds of feet into San Pablo Bay.

The property’s only road, a single-lane dirt affair called Goodrick Avenue, has provided vehicle access to the site since 1915. For much of the last century, its main traffic has consisted of dump trucks. The same is true for the bridge over Rheem Creek, a waterway that enriched the marsh with periodic floods of freshwater until the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers channeled it for flood control in the 1960s.

-

Native plants like the marsh gumplant will become a lot more common once the park district begins large-scale restoration and replanting. Photo by Pete Veilleux.

Despite this degradation, the parcel still provides critical habitat for protected species, including the California clapper rail and the salt marsh harvest mouse. In an odd twist of fate, the extensive fill that once destroyed the marsh is now one of its greatest assets. As sea level rises in the San Francisco Bay–scientists project a rise of approximately 55 inches by the end of the century–many existing tidal marshes will be submerged. At Breuner, however, today’s higher-elevation grasslands may well become tomorrow’s marshland.

The park district’s restoration plan entails the movement of up to 120,000 cubic yards of existing fill, which will be pushed from lower elevations to higher to allow the tides back in. In some cases, a change of only six to eight inches will suffice.

In future years, as sea level climbs, bayshore habitats–subtidal, mudflat, low marsh, high marsh, seasonal wetland, and finally upland–will march upslope to the extent they can keep pace, and as long as there is more open land available. The Breuner site will be designed to stay functional, both ecologically and recreationally, through five feet of sea-level rise.

“The current marsh’s [habitat] will shift from harvest mouse in pickleweed marsh to clapper rail in cordgrass marsh to shorebirds in the tidal flat,” said project manager Brad Olson. This forward-looking feature of the park’s planning is one of its greatest selling points. But it’s also costly: Around $2 million will go to a 10-foot-wide, 1,800-foot-long concrete boardwalk raised 12 feet off the ground to ensure public access despite sea-level rise.

Habitat values are at least as important as recreational access. Already, 90 percent of the Bay’s tidal wetlands have been lost to fill and development, and more will be inundated by rising seas. Many existing tidal marshes around the Bay are both shallow and backed up against developed shoreline, with nowhere to retreat in the face of rising waters.

While many of the South Bay’s restored salt flats are expected to fare better due to sedimentation and careful planning, the park district’s past marsh-restoration projects at Martinez, Hayward, and Martin Luther King Jr. regional shorelines will be endangered far sooner than Breuner. Much of Eastshore State Park’s salt marsh is also in peril. The park district hopes to incorporate sea level-rise planning into its forthcoming renovation of Albany Beach, but the low elevation of the parking lot directly behind it doesn’t leave much room to maneuver.

-

View of Breuner Marsh. Photo by Sally Rae Kimmel.

Breuner Marsh represents only 0.1 percent of the region’s tidal marsh, but sites like it with open uplands will become increasingly important as waters rise. By the end of the century, it could be in rare company.

In 2011, when the park district’s plans were beginning to take shape, Dotson, who still lives at Parchester, led me on a tour of Breuner Marsh.

The marsh is his personal backyard and former playground, where as a child he swam in narrow channels and marveled at the many birds gathered along the shore. “At a young age, I noticed the birds but I didn’t have any interest in identifying them,” he said.

Now, he identifies egrets, osprey, herons, kites, and myriad other birds–hundreds of them–feeding and resting and looking entirely at home on a gray winter morning. “All of this was the essence of the foundation for developing my interest in open space,” he said. “From a habitat standpoint, we need this as much as any bird or harvest mouse.”

We followed Goodrick Avenue north toward Point Pinole and turned west on a spur trail leading down to the Bay on a short jetty built up with concrete riprap and imported fill. Off to one side, I saw a dozen car tires half-submerged in mud, jutting upright at odd angles from the Bay floor as if dropped haphazardly from the heavens. Off the other side, a swarm of shorebirds fed furiously on the mudflats at low tide.

As at the Albany Bulb and Eastshore State Park farther south, nature is reclaiming a former dump at Breuner. Dotson’s intention is to give it a little help. Most of those tires have since been removed, along with huge loads of trash and debris from elsewhere on the site–metal poles, remnants of wooden structures, creosote timber, abandoned power lines. Volunteers made quick work of these eyesores during a handful of cleanup days organized by Dotson, other residents of Parchester Village, and the North Richmond Shoreline Open Space Alliance, of which he is president.

Already, plants such as alkali bulrush, marsh gumplant, ragweed, meadow barley, slender sedge, and California oatgrass grow here, and the site is visited by wildlife including ruddy turnstones, American avocets, killdeers, snowy egrets, coyotes, and western fence lizards. Their presence holds promise for the future.

A more recent visit to the marsh with the park district’s Olson brought out the other side of the story–all the work that still needs to be done. After four years of a difficult but ultimately successful eminent domain process helped by extensive community support, the park district paid $6.85 million for the property to Don and Lonnie Carr, who had bought it from the Breuners in 2000. The agency plans to spend another $8 million on improvements, with funds from a patchwork of local, state, and federal grants, plus Measure WW bond money.

Beyond rearranging fill with earth movers–a new bridge will first be built just to get the massive machines across Rheem Creek–the district will ship around 10,000 cubic yards off-site, at considerable expense. A small pile near the parcel’s north end was found to be contaminated with arsenic and may have to be sent as far away as Utah.

But first, Olson says, the park district will remove troublesome invasive species like fennel, bristly oxtongue, and eastern cordgrass. He points them out as we walk along Goodrick Avenue; many nonnatives crowd the road and extend well into the disturbed upland areas. Later, after grading work and topsoil restoration are complete, workers will begin to revegetate the site. The uplands areas will be seeded with natives, while the lower, wetter areas, more resistant to invasives, will be allowed to reestablish naturally. It could take at least two to five years for the flora to fully recover, he says.

The park district will cut three new channels into the marsh, facilitating tidal flooding and saltwater circulation in the service of 24 new acres of salt marsh. Just over seven acres of seasonal wetlands will also be created or restored.

Around 100 acres of the project area will be given over to critical coastal prairie habitat, which once covered East Bay slopes from the hilltops to the Bay; proportionally speaking, it’s even more endangered than wetlands. Fortunately, nearby Point Pinole is among the region’s few remaining prairie hot spots, says parks district grasslands specialist David Amme.

Olson expects to see biodiversity blossom after work is complete. “The coastal prairie areas would be particularly suitable for ground-nesting birds, such as western burrowing owl and northern harrier,” he says. “Tidal marsh could also be used by clapper rail for nesting. Waterfowl and shorebirds could nest adjacent to the seasonal wetlands, and the transition areas would be used for cover during high tide events and for small bird nesting.”

Access for human visitors will be incorporated rather discreetly. Parallel to the site’s eastern edge, near the 15-foot berm topped with Southern Pacific Railroad tracks that separates Parchester Village from Breuner Marsh, a long-planned 1.5-mile Bay Trail segment will be built. Connecting Goodrick Avenue to Point Pinole, the walkway will tie the two parts of the park into one.

Near the middle of the property, a shorter spur trail will jog west to an elevated viewpoint (birders take note) atop the tallest existing mound of fill and then to the lower-elevation jetty, which will be accessible only as long as sea level allows.

Continuing on our tour, Olson and I pass a turnoff leading to a small parking lot and, behind it, a 300-foot runway sitting incongruously in the center of the property. Equipped with two open structures for shade and seating, it’s the home of the Bay Area Radio Controlled Society, a remnant of former landowner Breuner’s love of aviation. Though empty now, the facility is still used regularly by club members, Olson said. It will eventually be demolished, and the radio-controlled airplane enthusiasts will have to find a new home.

But buzzing planes and roaring trains aren’t the only unnatural noises here: Gunshots frequently ring out over the Breuner property, disturbing the peace and startling birds. They come from the Richmond Rod and Gun Club, the marsh’s closest neighbor to the south. Today it is quiet, lending the land a remote stillness that’s rare along the Bay shore.

Near the end of our tour, along the property’s northern border and adjacent to Point Pinole’s healthier Giant Marsh, the roadway and surrounding fill level drops to only a few inches beyond the influence of the tides. “It won’t take much work in here to get this back to salt marsh,” Olson says. Beneath us, pioneer pickleweed plants grow in a narrow strip between ruts in a road that once served the marsh’s destruction.

At Breuner, it seems nothing admits defeat.

.jpg)