Does San Francisco have a healthy enough native bee population to pollinate the city’s agriculture?

Andrew Potter, a former San Francisco State University graduate student and now an environmental consultant, asked himself that question a few years ago after learning that not enough bees live in “pollinator deserts,” such as California’s Central Valley, to provide adequate pollination service to plants. He wondered if urban San Francisco shared the same challenge.

Potter, along with SFSU biology professor Gretchen LeBuhn, designed a study that measured the pollination service of the city’s native bees. The study, published in January in the journal Urban Ecosystems, found that the native bee population, indeed, supplies “adequate pollination service” for the city’s agriculture, including parks and gardens.

The results are surprising since previous studies have found that urban environments have lower bee populations and fewer bee species than surrounding areas. Urban growers should take heart, as there are 150 native bee species in San Francisco, LeBuhn said.

“It is pretty clear that there is sufficient pollinator service for urban agriculture from native species alone,” LeBuhn said. “We don’t need to add honeybees to have pollination (in the city).”

Nevertheless, honeybees remain a part of the fabric of San Francisco’s urban agriculture, where beekeepers harvest and sell honey to a retail marketplace hungry for locally made products. Those honeybees may not be needed, strictly speaking, to pollinate urban gardens, but they do so anyway.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Ways to help native bees:

- Create a bee garden with wildflowers native to your area

- Choose wildflowers with blossoms of varying size and shapes, and with varied bloom times to support a diverse bee population

- Plant in 3 to 4-foot wide color blocks of the same flower species (bees especially like purple, blue, white and yellow flowers)

- Keep your garden pesticide and herbicide free

- Leave an area of bare dirt where ground nesting bees can tunnel

- Make stem bundles of plant material for wood-nesting bees

- Create a bee block as a nesting cavity for bees

In the study, Potter and LeBuhn selected a plant that native bees favor — the cherry tomato plant. The pollen of tomato flowers is significantly more accessible to native bees than honeybees because native bees access the pollen though a technique called “buzz pollination,” in which the bee’s flight muscles sonicate the flower to release pollen. Honeybees, on the other hand, are incapable of sonication and thus avoid tomato plants if other floral options are available.

LeBuhn and Potter randomly selected 18 urban gardens from a list of more than 200 in the city as study sites and placed three tomato plants at each site. Each of the three plants was divided into four inflorescences, or flower clusters. The researchers covered three of the clusters with “pollinator exclusion bags” and left the last one open for native bees to pollinate.

The covered clusters were given differing pollination treatments. The control group was self pollinated, and researchers used artificial methods of pollination in the other two groups. In one, Potter used a middle C tuning fork to mimic bee sonification in order to release pollen from the plant’s anther cones, which make up part of the male plant organs. The other involved dipping the female parts, the stigmas, of the experimental flowers in sonicated pollen gathered from other plants.

Results from two of the sites were excluded because of aphid infestation and wind damage. After two weeks on site busy pollinating, the plants made it back to an SFSU greenhouse to finish their growth under uniform conditions. The researchers measured tomato weight, the number of tomatoes on each plant, the number of flowers that matured into tomatoes and the number of seeds per tomato cluster.

The study found that the plants where native bees did their work out in the open yielded the highest amount of fruit than the other test cases. Potter and LeBuhn concluded that the native bees are able to adequately pollinate plants that, like tomatoes, are not restricted to a certain bee species.

Much to the scientists’ surprise, the study also found that the amount of impervious surfaces, such as buildings and fences, does not hinder pollination service in the city.

“If you think about it from a bee’s perspective, flying over downtown San Francisco is not particularly welcoming,” Potter said. “But the bees were capable of navigating that environment while providing the ecosystem service of pollination. That is good news for both bees and farmers.”

The study also indicates that the number of bees attracted to a garden plot has more to do with the density of flowers than the size of the garden. That’s also good news to space-limited gardeners, who can add more flowers to boost fruit and vegetable yields, and one more reason to support native bee populations by planting native flowers and avoiding the use of pesticides and herbicides.

LeBuhn has launched The Great Sunflower Project in 2008 as a way to engage the public in the conservation of pollinators and gather important data for research. Participants record the pollinators they see in their gardens, parks and schools, and now has a tool to allow them to evaluate their pollinator spot and receive customized suggestions on how to make the space more bee-friendly. Over time, researchers will get a better sense of which interventions are effective and which are not.

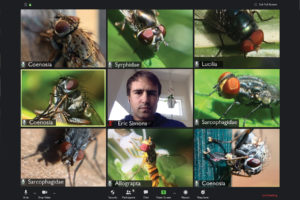

Here is LeBuhn discussing The Great Sunflower Project: