The following is adapted from the Napa River Historical Ecology Atlas, a new book by Robin Grossinger, director of the Historical Ecology Program at the San Francisco Estuary Institute. The book is the result of 10 years of study of the Napa Valley, combining exhaustive research into historical documents and exploration of the landscape today. It is perhaps the most in-depth look at the historical character and transformation of any river in our region.

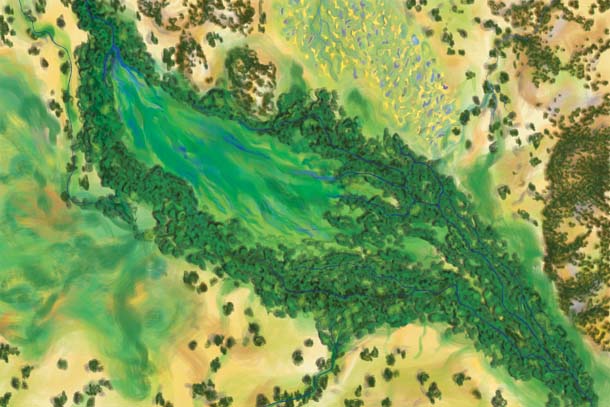

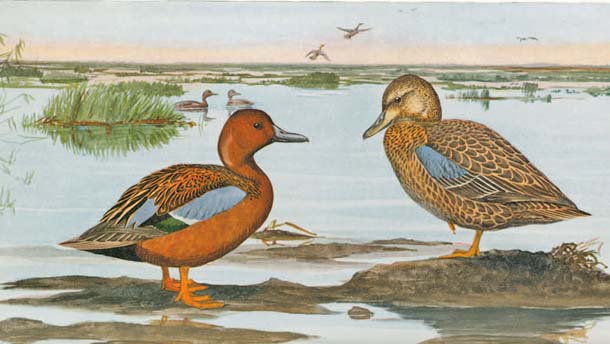

Its headwaters can be found in the deep canyons of Mount St. Helena, on the northern margin of the Napa Valley. Seeps and springs trickle into small creeks that emerge onto the valley floor, initiating the complex, interacting system of vegetation, sediment, and water we call the Napa River. Today, the river mostly follows a single deep channel through the vineyards of this world-famous wine region. It is easy to assume that the sinuous, tree-lined, river retains much of its original character. But historical records show that the Napa River once differed greatly from the way it looks and behaves today. Compared to conditions in the recent past, the present river turns out to be simplified and constrained, retaining only remnants of its previous wild and diverse nature. These patterns explain how the river supported salmon and now-rare birds like the yellow-billed cuckoo. Understanding how the river once worked can help us figure out how to improve its health in the future. In fact, a number of restoration efforts currently under way seek to re-create some of the river’s former complexity.

- In the early 19th century, the Napa River grew and changed dramatically as it headed down the valley. It received mineral-rich overflows from the hot springs at Calistoga, met perennial tributaries at Mill and Ritchey creeks, and absorbed sand and gravel from streams in its middle

reaches. Alluvial fans and bedrock knolls deflected the river’s course from side to side. As the river approached San Pablo Bay, it widened into vast tidal wetlands. The river supported broad riparian forests in some reaches and floodplain wetlands in others. Over 30 miles of side channels branched out across the valley bottom, doubling the river’s effective length and providing forage and refuge for young steelhead. Native minnows lived in warmer water; steelhead and (likely) chinook salmon fed in the deeper pools. For thousands of years, people fished and swam in the river’s cold pools and reclined on its gravel beaches.

The Napa River remains the valley’s spine, its central geographic feature. Yet it shows signs of distress. The river is listed as impaired by sedimentation under the Clean Water Act, and increasing local water demand may threaten dry season flows. While the Napa River has not been transformed to the same degree as have many other California streams, it has been significantly altered, losing much of its complexity in the process.

Today, the Napa River may be on the brink of another transformation. For two centuries, it has been modified, polluted, and restrained. Now, barriers to fish migration are being removed and the presence of steelhead and salmon has been increasingly documented in recent years. In the past decade, several large-scale restoration projects have begun. It is possible to recover some of the Napa River’s former glory and, in the process, restore the health of one of the Bay’s most important tributaries.

-

Some riparian woodlands remain, as at the Napa River Ecological Preserve near Yountville. Photo by Robin Grossinger.

Riparian Forest

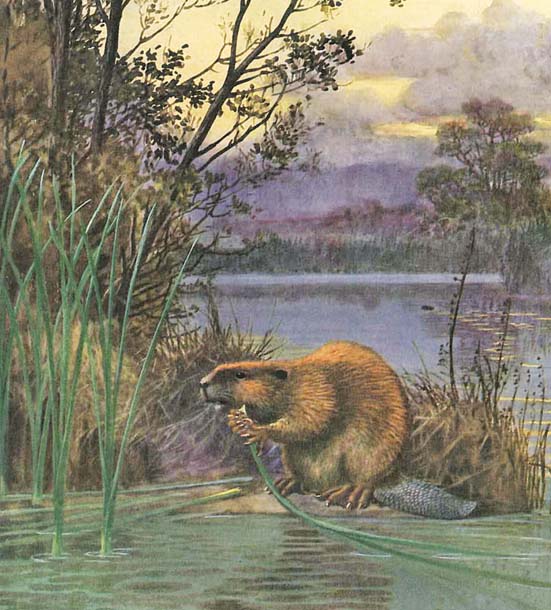

Today much of the Napa River is bordered by thin strands of riparian forest, 50 to 100 feet wide on each side. Research suggests that many riparian wildlife species need much wider forests–100 to 500 feet or more on each side of the channel. Broad riparian forests provide nesting sites for wood ducks, yellow-breasted chat, and yellow-billed cuckoos; cover for elk and deer; and food and building materials for beavers.

Several lines of evidence indicate that historically the river featured a much wider forest than exists today, supporting diverse native species. For example, forest remnants 200 to 400 feet wide can be seen upstream of St. Helena in early 1940s aerial photography. On the lower Napa River near Zinfandel Lane, 19th-century surveys documented even wider willow-dominated forests associated with side channels of the river. An 1871 article suggested that willow lands covered substantial areas along the river and foreshadowed their clearing: “I cannot help thinking how much better it would be for all parties if land-holders would sell these waste lands [along the Napa River] . . . to such of those as would make a thorough business of clearing out the useless willows and covering the broad and fertile acres with blackberries, gooseberries, currants, or other fruits.”

Beavers have recently been found in the Napa River for the first time in years–in the vicinity of Rutherford and downstream of Oak Knoll. But were they there historically? Early naturalists speculated not. And John Work, one of the earliest trappers to come through the North Bay, wrote of the Napa River in 1833: “The little river where we are encamped at appears very well adapted for beaver yet there appears to be none in it.” But six weeks later, the expedition sent a side party to the river, where they had earlier “found a few beaver.” Work also reported beavers a few miles away in the Sonoma Creek watershed; other sources also support the historical presence of beaver on the river. Trapping likely removed most beavers from the watershed by the 1840s. Before then, beaver dams would have increased the extent and persistence of wetlands along the river even beyond the amount documented in the 1850s and 1860s. In other regions, the importance of beaver ponds to salmon populations and overall stream function has been increasingly recognized, and their return can potentially help speed river recovery.

The River Spread Into Wetlands

In the fall of 1852, a survey team followed the Napa River, using compass and chain to record the meandering course of the river as an official cartographic and legal boundary. Just north of Dry Creek, the character of the river abruptly changed: The channel disappeared, leaving no dividing line to survey. County Surveyor Nathaniel L. Squibb had encountered one of the Napa River’s great marshes. He wrote: “Has the Napa River a distinct channel at that point or any channel at all? I examined the place and could not find a channel at that point similar to the channel above or below.” Farther north, near Zinfandel Lane, the main channel spread into several smaller sloughs winding through extensive “swamp and tule.” Off-channel wetlands such as these contributed an array of valuable functions, storing surface water and fine sediment and likely providing high-quality rearing habitat for steelhead and salmon.

Within a few decades, Squibb’s wetland–and many similar environments throughout the state–had been drained and forgotten.

Islands and Sloughs

At least 32 miles of floodplain sloughs, or side channels, once branched from the river’s main stem, running roughly parallel before rejoining the river downstream. Ranging from 10 to 50 feet wide, these features extended both aquatic and riparian habitat well beyond the primary channel.

The sloughs branched through mosaics of wetlands, riparian forest, and seasonally flooded meadows, defining distinct “islands” (the largest, near Yountville, was over 300 acres). Particularly in the lower half of the valley, the Napa River’s floodplain sloughs contributed to the river’s productivity. Given the surrounding permanent wetlands, some sloughs likely had perennial water. Slow-moving, well-wooded backwaters supported wood ducks and beavers, while providing rearing habi-tat and high-flow refuge for juvenile salmonids and other native fishes. As these side channels have been filled in and disconnected, the main channel has had to carry more water.

Going Deeper

While the Napa River has not been converted to an engineered channel like many other lowland rivers in California, it has experienced many of the same effects. The channelization and draining of wetlands, the disconnection from side channels, the decline of beavers, the removal of riparian forest, and the loss of woody debris all have contributed to the transformation of a once-diverse river into a straight chute, a water highway. Yet the river also demonstrates the resilience and ecological potential that we see in many California landscapes. The changes, while dramatic, are relatively recent. Many native plants and wildlife are still present, or even returning. As we attempt to make our watersheds ecologically healthy, safe from flooding, and resilient to climate change, these forgotten elements may have a role to play in our future. The lessons of 1850 may shape the river of 2050.

Learn more

This is just a small slice of SFEI’s full Napa Valley Ecology Historical Atlas, published by UC Press ($39.95, ucpress.edu). You can also discover more about the river through the Friends of the Napa River [friendsofthenapariver.org, (707)254-8520] and the Watershed Information Center and Conservancy of Napa County [napawatersheds.org, (707)259-5936].

.jpg)

-300x199.jpg)

-200x300.jpg)