The uniform columns of charcoal-colored lava claim your eye as soon as you scan the horizon above the Napa Valley resort town of Calistoga. There is something of the Badlands in their appearance that, if you’re like me, instantly makes you wish you knew more about geology. This vertical bank of andesitic pillars, called the Palisades, rough-hewn even when seen from a distance, ranges for four miles to the west across the face of the Mayacamas Mountains. It is the proverbial tip of the submerged iceberg–60 miles long, 20 miles wide, and 4,000 feet thick, this slab of rhyolite and obsidian is known among geologists as the “Sonoma Volcanics.” The 3.4-million-year-old formation is crowned by the imposing mass of Mount St. Helena. But enough science–what do the poets have to say about the matter?

“Three counties, Napa County, Lake County, and Sonoma County, march across its cliffy shoulders. Its naked peak stands nearly four thousand five hundred feet above the sea; its sides are fringed with forest; and the soil, where it is bare, glows warm with cinnabar,” wrote Robert Louis Stevenson in his book The Silverado Squatters.

When the state park was established here in 1949 the name Robert Louis Stevenson was chosen because of the summer the famous Scot spent in 1880 honeymooning with his bride on the side of Mount St. Helena. (Scenes informed by his stay show up in the novel Treasure Island.) What had attracted Stevenson–the fog-free weather up the mountain and the heat both above and below ground–still fuel the local attractions, now complete with hot water and mud spas, wine tasting, and hot air ballooning.

And the attraction for the rest of us, the canteen-laden and soon-to-be-sore-legged? Hiking challenging wilderness terrain and learning the names of the local flora and fauna as we go, as Stevenson did: “Our driver gave me a lecture by the way on California trees–a thing I was much in need of, having fallen among painters who know the name of nothing. . . . He taught me the madrona, the manzanita, the buck-eye, the maple; he showed me the crested mountain quail; he showed me where some redwoods were already spiring heavenwards from the ruins of the old; for in this district all had already perished: redwoods and redskins, the two noblest indigenous living things, alike condemned.”

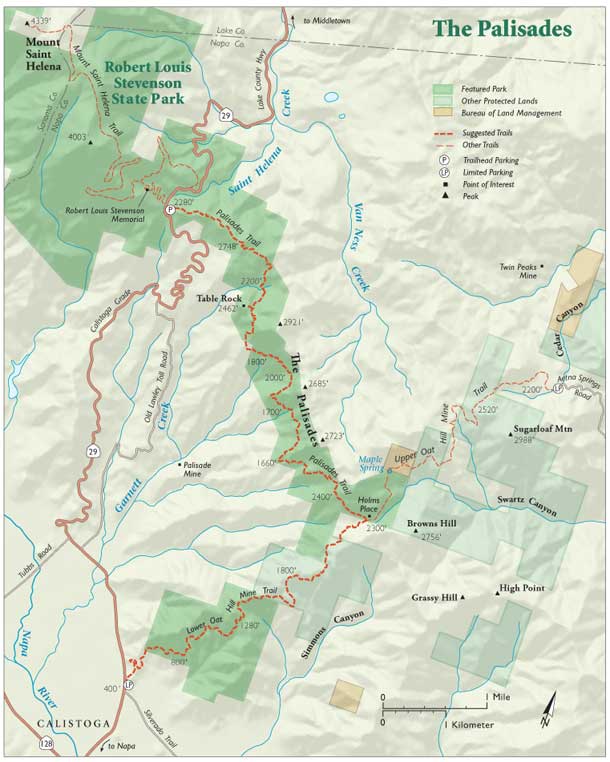

While the Palisades Trail, located to the east of Mount St. Helena on the panhandle of Robert Louis Stevenson State Park, is open year-round, you should consider hiking the Palisades a three-season proposition. Leave out summer, due mostly to the oppressive combination of high temperatures and steep rocky terrain: When the trail was being built in the late 1990s, California Conservation Corps members were given the summers off. In spring, the wildflowers on the way to Table Rock and beyond, along the Palisades and Oat Hill Mine trails, are as profuse and varied as anywhere in the Bay Area. According to native plant enthusiast Dick O’Donnell, who has been hiking the area for decades, between April and June you are likely to see the full array of wildflowers at all stages of development. Last spring there were glorious turnouts of wildflowers both in mid-April and late May when I hiked the trails. Fall and winter, though they cannot compete with the teeming spring displays of color, feature their own mellow earth tones (thanks mostly to the deciduous white and black oaks and big-leaf maples) and mild temperatures, as well as the stark visual contrasts produced by the rare snowfall.

- Phacelia, Indian paintbrush, lupine, and sticky monkey flower bloom along the trail in spring. Photo by Reny Parker, renyswildflowers.com.

Many hikers opt to carpool to the upper trailhead and work their way down the strenuous 11-mile route, rather than double back. Like so many State Park trails, this one has seen little maintenance since being built. The fact that the trail got built at all is something of a miracle, says former ranger Bill Grummer. From his arrival in 1973 until his retirement in 2005, with only nominal support from park managers, Grummer got involved in all aspects of the trail’s evolution, from acquisition on through dedication in October 1999. He often volunteered on his days off to assist John Hoffnagle and others from the Land Trust of Napa County; without them, he says, “the trail never would have happened.” The trust persevered for nearly a decade, negotiating with various government agencies and private landowners to stitch together acreage and easements needed to complete the trail.

The Palisades had always attracted attention: Sierra Club hikers and their minimalist trail constructors would push through on periodic treks to summit the Palisades in the 1960s and ’70s, when much of the route was cross-country guesswork in steep, chaparral-choked terrain. Those legendary “death march” hikes, as they came to be fondly remembered by hardy participants, used to traverse the top of the Palisades, not 700 feet below along their base where the route runs today. The Livermore family, who 50 years earlier had donated land to establish Stevenson State Park, wanted to protect the mineral water source in the upper reaches of the Palisades and persuaded the State Park to relocate the trail. At the time, Grummer recalls, this was a major disappointment to fans of the Palisades, himself included. But he soon came to see it differently. Though our natural inclination is to “peak-bag” and climb, as Grummer puts it, “as high as possible,” the current layout affords views that are just as dramatic.

- Numerous springs emerge from the fractured rocks of the cliffs here, creating small, wooded oases along otherwise unshaded portions of the trail. Photo (c) Samanda Dorger, samandadorger.com.

To take advantage of Grummer’s handiwork yourself, go to the Table Rock trailhead on Highway 29. You warm up on old utility roads before you get to an opening with views to the north of forested ridges that disappear into the wilds of Lake County. Soon, you’ll have your first views of the Napa Valley among the scattered lunar rock formations and the sparsely vegetated, mostly stony meadows known by locals as the “Craters.” Two miles out from the parking lot after passing through a rock art labyrinth and dropping into and climbing out of a fern- and giant trillium-dotted canyon, you come to a large plateau of overlapping flows of naked rock geologists call tuff–solidified volcanic ash. (The rocks of Mount St. Helena and the Palisades are volcanic in origin, though the formations themselves are the result of tectonic uplift.)

As promised, a wide variety of wildflowers greets you everywhere you turn: in mid-April, milkmaids, buttercups, golden poppies, hound’s-tongue, fiddleneck, monkey flowers, bunches of normally sparse shooting stars and carpets of goldfields; later in May, fairy lanterns (globe lilies) and scarlet larkspur, elegant brodiaea and bitterroot, sprays of lupine and penstemon. The shrubby understory of mixed woodland and evergreen (oak/madrone/gray pine/Douglas fir) features ceanothus, gooseberry, and both common and Stanford manzanita, covered in white and pink blossoms even into May.

Desolate and exposed Table Rock, once you have climbed onto it, is flat only in comparison to the surrounding terrain that tends toward the vertical. Car-size boulders that now rest on the table are volcanic “bombs” that were hurtled through the air during an eruption three million years ago. The rock here is rhyolite, lava that when hot had the viscous texture of peanut butter.

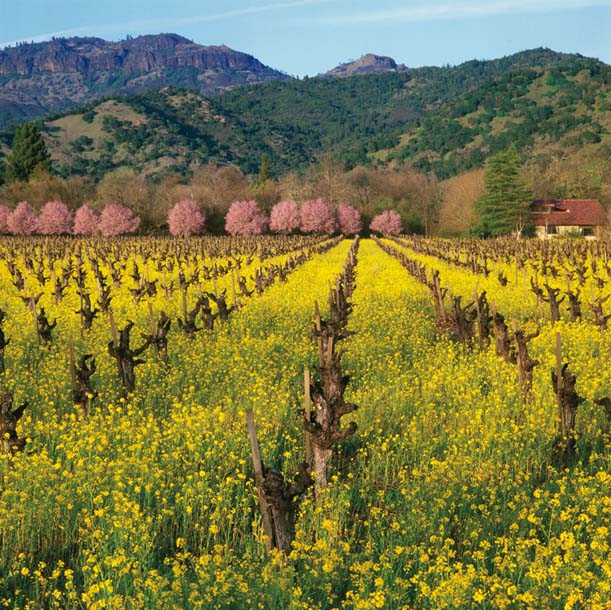

- From the floor of the Napa Valley, with mustard in bloom, the Mayacamas Mountains beyond form a perfect postcard backdrop. Photo by Ed Callaert, edcallaert.com.

Behind and 2,000 feet above you, Mount St. Helena reminds you of your starting point, while ahead views of the vineyard-covered valley floor and distant coastal ranges appear: the Mayacamas, and beyond them the Sonoma Mountains. To the southeast the twin peaks of Mount Diablo rise from the haze.

From this point eastward you descend a series of narrow switchbacks that bring you out to the western edge of the Palisades. The ridge of hard rock pushed up by crustal buckling has been sculpted by wind and rain; cliffs that looked merely rough from down in Calistoga appear starkly jagged up close. Here you understand the significance of the decision to locate the trail below the columns, some of which rise 700 feet above the trail surface. You may also notice their darker color compared to Table Rock; the Palisade rocks are lower in silica content and are made of volcanic ash deposits, welded tuffs, that accumulated below the surface and rose up while still semimolten through pipe-like openings in the earth’s crust to form towers. At one point along the south end of the trail the columns take on the hexagonal pencil shape familiar to us from places like Devils Postpile.

The trail levels out at the base of the Palisades and the skinny single track hugs the steep slopes across the four-mile run of columnar outcroppings. Grummer says this section of the trail, the most inaccessible, was built first to discourage premature use; after two or three years, either end was built, brutally difficult work that exhausted various trail crews until the trail was finally complete.

- Poppies and lupines are plentiful along sunnier sections of the trail. Photo by David Jesus, davidjesus-naturephotography.com.

The trail dips in and out as the dark cliffs follow an undulating rather than a straight line. Both eerie and charming, the diminishing returns of a canyon wren’s distinctive call echo around you. Despite the proximity of the monocultured valley below, here the beauty and ruggedness of the terrain and the profusion of the wildflowers produce an adrenaline rush that says you have entered a truly wild place. In the interior recesses, spring-fed streams gurgle down rocky drainages, creating miniature riparian zones and feeding the colorful sprays of wildflowers out into the bordering grassland. Especially in the dry heat of summer, these deep green nooks offer habitat variation that would be missed on a trail situated along the crown of the Palisades. Also hidden from a summit viewpoint is one of Grummer’s favorite parts of the trail: Just before descending to the intersection with the old Oat Hill Mine Trail, you’ll pass through cave-like formations overhung by craggy towers.

Turkey vultures expertly ply their trade on thermals above the dark rocks. The cliffs are also home to aerially acrobatic peregrine falcons–indeed, one of the variant names of these rocks is the Peregrine Cliffs. Long before they became endangered, in the 1890s (10 years after R. L. Stevenson’s visit) peregrines had been noted nesting high up Mount St. Helena. The species suffered for decades, especially from DDT-thinned eggshells, but in 1977 Grummer saw a nesting pair that fledged three young. The vertical rocks of the Palisades still provide ideal habitat for their descendants.

Six or seven miles in from the trailhead at Highway 29 you join the Oat Hill Mine Trail, at an historic homestead site belonging to a farmer named Holm; some fruit trees and a stone wall are the only remnants of this place known as Halfway House because of its location midway between Calistoga and the 200 souls who inhabited the settlement at the Oat Hill Mine.

- Map by Ben Pease, peasepress.com. Click image for a larger version.

I picked up a pocket-size piece of cinnabar on the trail under the towers of andesite. This stone contains sulfur and mercury; when crushed and heated, the sulfur burns away, leaving vapor to condense into the valuable liquid metal once called (rather poetically) quicksilver. This mercury (as we prosaically call it today) was used during the late 1800s to process silver and gold in mining operations in California and Nevada. Here, nearly 150 years ago it was collected in metal flasks that weighed 75 pounds and carted down the Oat Hill Mine Trail by mule-drawn wagons to the railway station. This mine, from 1872 until the late 1960s when it finally ceased operations, produced one third of the nation’s total output of quicksilver.

Today, the Palisades Trail ends at this intersection with the Oat Hill Mine Trail, and the old wagon road, originally dynamited out of the mountainside, winds for four miles in either direction, uphill and downhill. Down takes you to the valley floor (plunging from 2,300 feet to 350 feet) to the outskirts of Calistoga. Along the way, look for the wheel ruts carved into the soft volcanic stone by those mercury-laden wagons.

As you descend to Highway 29, you may well feel you have survived, and joyfully, the closest you can come to a wilderness experience at an upscale edge of the Bay Area. You get the idea, as did Robert Louis Stevenson, that habitat modification and loss have been perennial themes in the natural and cultural history of the Coast Ranges, and that hiking on trails like this one is more healing than ever.

Getting There

The Table Rock trailhead is north of Calistoga, on the east side of Highway 29 across from the Mount St. Helena trailhead. For a one-way hike, leave a car at the Oat Hill Mine trailhead, at the junction of Highway 29 and Silverado Trail. This is a rugged trail, so it’s important to bring enough water and food, and let someone know when you plan to return.

.jpg)