Q: I’ve heard stories that ringtails were known to “shack up” with miners during the Gold Rush, yet in 20 years as a wildlife biologist in California with many night surveys in likely habitat, I have encountered two mountain lions, but no ringtails. Where are the ringtails? [Wendy, Martinez]

A: I, too, have wondered about the lack of ringtail sightings in my nocturnal forays. From historical accounts, you’d think every prospector’s cabin had its own family of ringtails, keeping lonely miners company and the area free of rodents. At only three pounds, these diminutive critters are smaller than a house cat, but they’re right up there with sea otters on the cuteness scale–9.9, I’d say. While commonly referred to as “cats,” they are actually related to raccoons and coatis and more distantly to pandas! And they behave much more like weasels than like raccoons. Their short legs give them a feline look, but their heads resemble those of small foxes. Their scientific name, Bassariscus astutes, means “clever little fox.” And their namesake bushy tail, banded in black and white, is as long as their 12-inch body. Adapted for nocturnal foraging, ringtails have huge eyes, large ears, and a keen sense of smell. They also have sensitive whiskers called vibrissae that grow not only by their mouths but also above their eyes and on their wrists.

They’re elusive, but also very successful and widespread: Ringtails are found from Oregon to Mexico and east to Oklahoma in many different habitats from sea level to 9,000 feet. Ringtails thrive anywhere they can find food. What’s food for a ringtail? Just about anything–fruit, small birds and mammals, leaves, nuts, eggs, and insects–the latter making up about 40 percent of their diet. They are superb hunters and accomplished climbers. They can rotate their back legs 270 degrees, which helps them scale steep cliffs and leap from tree to tree. Their primary predators are probably great horned owls, which hunt using both dim light and sound. So it’s not surprising that ringtails are incredibly quiet and stealthy. That helps them elude those hungry owls while also nabbing their own unfortunate prey.

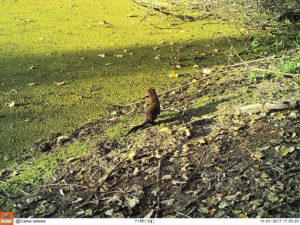

David Wyatt, a biology professor at Sacramento City College, has been studying ringtails for years. He has live-trapped and radio-collared a number of them in the Sutter Buttes and in riparian areas in the northern Sacramento Valley. He says that sometimes when he’s picking up radio signals and knows a ringtail is right in front of him, he often still can’t see it. But his research and the research of others indicate that ringtails continue to be numerous, though we rarely see them.

So don’t feel too bad, Wendy. At least you saw mountain lions!

Send your questions to atn@baynature.org.

.jpg)