Looking extinction in the eye.

illustration by Rachel Diaz-Bastin

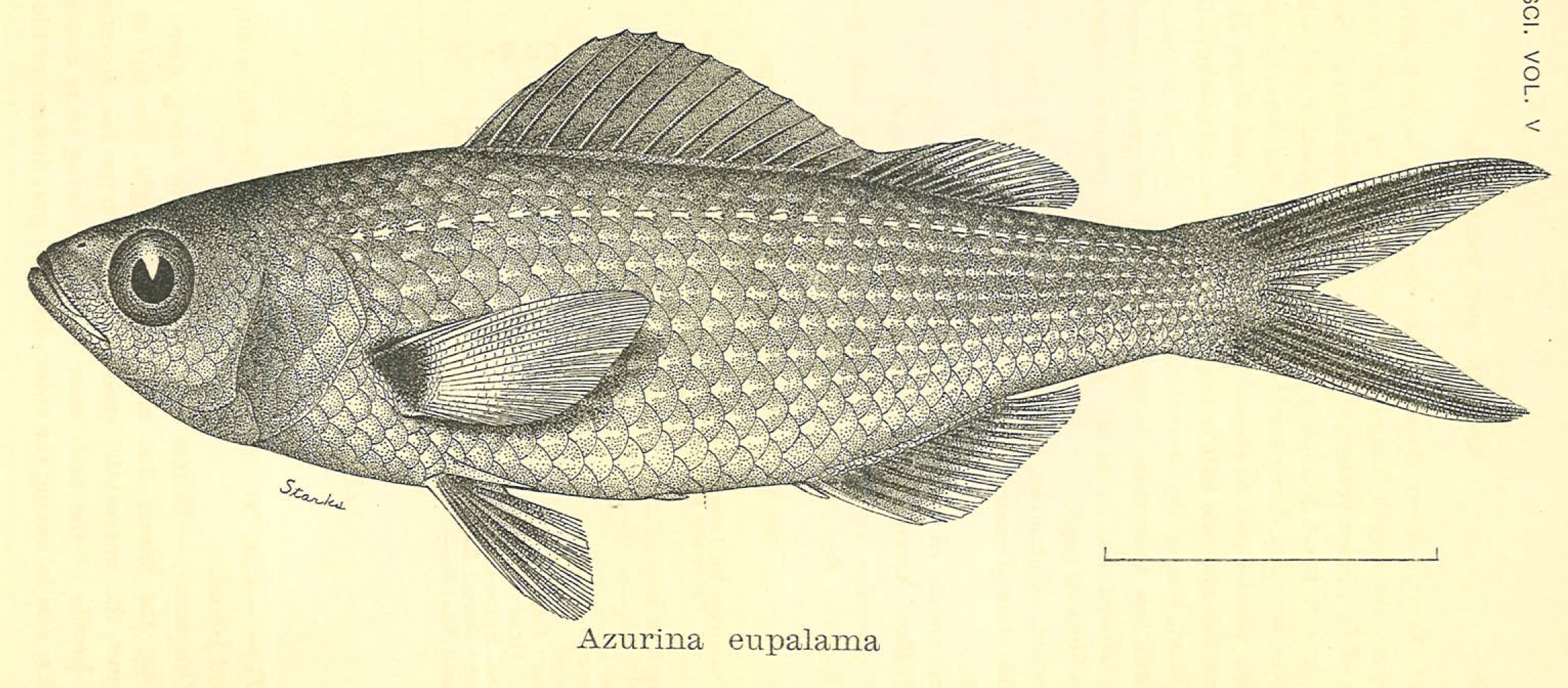

Once, not so long ago, there lived a fish in the Galapagos Islands. Its name was Azurina eupalama, the Galapagos damsel; it was not particularly different from any other small rocky reef fish. “Indistinct,” says California Academy of Sciences ichthyologist Luiz Rocha. “Small, silver. Looks like a sardine.”

In 1982, the strongest El Niño ever recorded created a huge pool of hot water around the Galapagos Islands. And then … no one ever saw the Galapagos damselfish again. No one’s ever missed it enough to mount an expedition to look for it, but it was one of those fish that scientific divers and snorkelers would record as they made their rounds, and it’s been 32 years since anyone has seen one alive. It is presumed extinct, which Rocha says would make it the first marine fish to go extinct while we’ve been watching. It would also, he says, be the first marine fish known to have disappeared because of a change in climate.

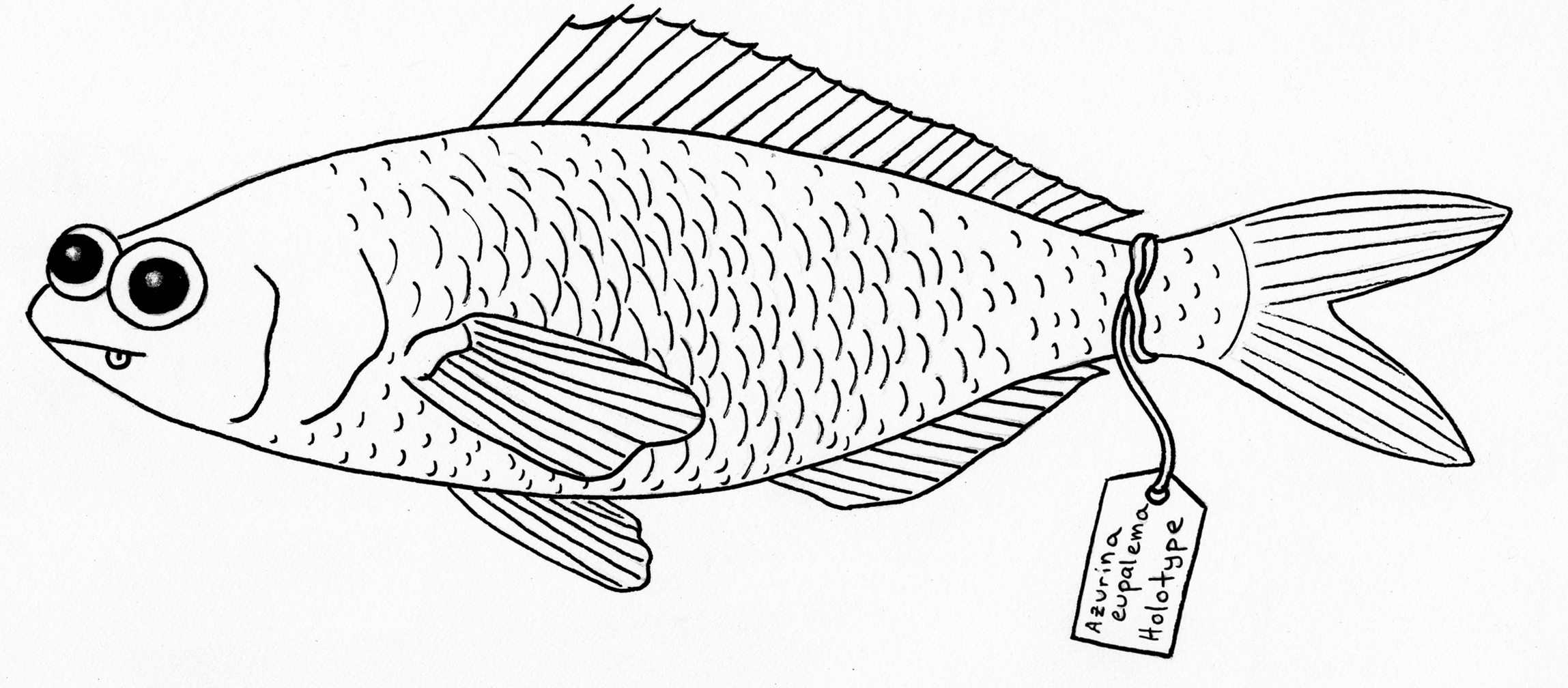

Today you can follow Rocha deep into the library-stack bowels of the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, and on a ceiling-high metal shelf that’s stacked with collecting jars, you can find a five-inch bottle with a nondescript typewritten label that says, “Azurina eupalama.” A blue ribbon tied around the lid tells Rocha that the little guy floating there in ethanol is the “holotype” for this fish, the single individual out of all the individuals in the world that will be forever linked to its Latin name.

This “type specimen” was collected on a Galapagos expedition in 1893 by Stanford biologist Edmund Heller, labeled and stored at Stanford and then assumed into the Academy’s collection in the 1960s. Some species are so common that Rocha is content to just drop their holotypes in the mail for other researchers to examine. With Azurina, he chuckles at the idea. Trusting the mailbox is not the kind of thing you can do when the 100-year-old thing in the bottle becomes irreplaceable.

Rocha twists the lid off and pulls the fish out. Its silver color has faded to yellow. Size and shape-wise, it looks like he’s holding a dinner sardine; you could picture it on toast. Rocha flicks at its pectoral fin to demonstrate the lifelike preservation granted by formalin injection. As we talk, he rests the fish gently on top of the open jar. I stare at the fish. Rocha stares at the fish. Out of an empty, black eye, the fish stares hollowly at the ceiling.

Azurina eupalama, rather manifestly, is not a fish that anyone misses. It does not exude charisma, like the dodo. It does not represent some great tragedy of American hubris, like the passenger pigeon. It is not the target of resurrection schemes, like the mammoth. Somewhat against the odds given everything else we’re doing to the planet, it was not even directly our fault that the Galapagos damselfish disappeared.

And yet: we’re now missing something out there in the world, and this little guy resting on the jar is a formalin-stuffed relic, a symbol of absence, of scarcity, of zero. Ever since Rocha first told me about it, several years ago, it has lodged in my brain, and I find that to examine it and hold it is in some small way to plug into the incomprehensible enormity of the universe. Its unique existence hints at answers, if only I could ask it the right question.

So I start with this one: As the Pacific Ocean heats again into what looks like an intense El Niño by December, as human-caused climate change stresses the natural world even as it puts us under more pressure to solve problems for humans first, Azurina must have a story to tell about what we lose when something we didn’t notice blinks out of existence.

“It’s a question I get often,” Rocha says, and he has his own ways of thinking about the answer, a blend of moral and utilitarian thinking about how to face a world in peril. “One answer,” he says, “is if my grandson goes to the Galapagos, he won’t see it.” Another answer is: “Every species has a role in the ecosystem,” even small and indistinct fish. “It’s not a panda bear,” Rocha says. “But everything has a role.”

John McCosker, the chair of the Academy’s Department of Aquatic Biology, who took the last photo of Azurina and wrote the paper suggesting it had gone extinct, has spent his life fighting to save life in the oceans — but says that without scientific knowledge, it’s hard to make any judgment at all about the value of an extinction. “Are we going to stop all life on Earth, all competition with living plants and animals?” he says. “It’s a question you have to ask. The way you can prepare to answer that is by knowing as much as you can about every species and their role in the ecosystem, and what would life on Earth be like after its extinction.”

That seems acutely relevant in the midst of the so-called Anthropocene extinction, as species both known and unknown hurtle into oblivion at, according to various estimates, some hundreds of times the background extinction rate.

Humming somewhere in Rocha’s brain is the urgency of documenting species as fast as he can, just so we have some idea the reach of our own blind thrashing. Earlier this year he went on a dive trip to the Philippines to collect fish from drowned coral reefs in deeper waters rarely examined before by humans. In a week he found 12 new species, almost one per dive, to add to the 32,000 fish species in the world. The ocean, at times, can seem like such a vast and limitless place, which is why marine biology professors, in the days when McCosker was a graduate student, would confidently declare we’d never run out of fish.

Now we are running out of fish.

“A lot of scientists have done all but immolate themselves over the potential loss of a species that they knew would go extinct, and has gone extinct, as a result of things that would happen in our lifetime,” McCosker says. “All we can do is the best we can, and grab and shake people and say, ‘Don’t you realize human behavior is going to cause the extinction of this species?’ And their reaction is either sadness or ‘So what.’”

Rocha told me he flew back from the Philippines, paused for six hours in San Francisco, and boarded a plane for Houston to join a meeting of the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Over the next two days he evaluated around 500 fish species for the IUCN, a global environmental organization that tries to assess the threat level for every species on Earth. (The little conservation status bar when you look up an animal on Wikipedia is their work.) The news is mainly grim, and one fish that crossed his desk in that evaluation happens to rest two jars down on the shelf from Azurina.

I had asked Rocha where he worries the next extinction might happen, and he slid over to a jar holding Halichoeres socialis, the social wrasse. The inch-long fish lives in only one small area in the Pelican Keys in Belize. Habitat destruction and mangrove clearing has left it without much resilience. If nothing is done — and it’s not clear what there is to do, except that we are people and when we find out about things like this we feel like we should do something — it will probably be eaten to extinction by human-introduced lionfish. In January, Rocha’s IUCN group declared it critically endangered.

It’s the something that’s always the problem.

We put the fish away in the jar, and reversed down the collection aisle, past biological riches that would take decades to understand. Rocha spun the wheel on the giant library-stack cabinets to pull them back together again, locking the extinct and endangered fish back in the anonymous darkness.

McCosker, a frequent Galapagos explorer and one of the last people to see Azurina eupalama alive, happens to have the office next door to Rocha, so on the way back from the collections we walked in, past a nameplate on the door that said “HEAD SHARK” and a Far Side cartoon about ichthyology signed by Gary Larson. What, I asked him, does he do to reconcile 70 years of scientific work studying marine life with the incredible peril much of that life finds itself in? How do you deal with the knowledge you’ll very likely never see another one of these fish again?

McCosker pointed to a photo of the Dalai Lama on his desk. “I do what he does,” he said. “It’s just a species in time, passing through, like you or me.”

“If there are other universes with ecosystems that because of natural events animals go extinct, and humans aren’t even there, am I sad?” he said. “No. But as a human being with the ability to understand what’s going on, and make predictions, I have a responsibility. A moral, ethical responsibility to do the right thing, and to convince other people to do the right thing. That’s the role of science.”

McCosker and Rocha both said that some form of life in the oceans will endure no matter what we do to them — because before we destroy everything around us, we’ll have destroyed ourselves. “I feel bad because we’re the ones causing it,” Rocha said. “But I don’t feel bad for the ecosystem.”

Compartmentalization is not an entirely comfortable way to go about your life, but it might be a necessary one. Modern biologists spend their lives looking at animals that may or may not make it into the 22nd century. It’s our own contradictory nature that our emotional brain screams at us to wrap our arms around an endangered fish and devote 80 hours a week to keeping it alive, even as our prefrontal cortex notes that 32,000 species times 80 hours a week leads to unsustainable work-life balance. It’s why, as Jon Mooallem writes in Wild Ones, “The best of us are cursed by caring.”

The biologist’s way of addressing the urgency of extinction is to document, evaluate, predict, and warn. You grab the new species that’s in front of you, and you do what you can to help each individual you come across, and you celebrate that in areas where protections are put in place the fish do come back, even if those places aren’t nearly sufficient and fish aren’t that great at observing human-drawn boundaries. “I continue to work,” McCosker says. “I’m long past retirement age, and I still go to work every day so I can do this. I still talk about this at every dinner party I go to. Every kids’ school group I attend. Whatever. It’s all I talk about.”

And he said one lesson of Azurina isn’t so much in the void left by its absence as it is that it disappeared without us fully understanding it.

“Will the health and ecology of the Galapagos change as a result of the loss of Azurina?” he says. “I don’t know, but I’d be surprised. It was never so abundant or so significant in ecosystem food webs that its absence will make much if any difference. But we’ll never know. We’ll never know because we just didn’t have a chance to understand them.”

That, I think, is what sticks with me most about Azurina. We’ll never know about the fish, and we’re uniquely able to understand what never means. We are, uniquely among the animals, able to be driven crazy by the mere knowledge of experiences we can’t have. We are uniquely able to look at the unrealized Platonic ideal that is Azurina and see it as more than just a dead fish.

“Hundreds of millions of years of evolution have produced hundreds of thousands of species with brains, and tens of thousands with complex behavioral, perceptual, and learning abilities,” UC Berkeley evolutionary anthropologist Terry Deacon writes at the beginning of his book The Symbolic Species. “Only one of these has ever wondered about its place in the world, because only one evolved the ability to do so.”

As minimal, as uncharismatic, as anonymous a fish as Azurina may be, it’s a symbol and a warning that we alone can see, and as such it seems to convey both the enormity of extinction and an utterly immense obligation.

Rocha and I stood and stared at that fish. We poked it, propped it, wondered about it. Rocha mentioned that Azurina is a lesson taught in grad school marine biology across the country.

But all the while the fish just stared out of that hollow black eye at the ceiling, and at some point you start to feel silly because, well, you’re interrogating a small, indistinct, sardine-looking thing that’s been sitting in preservatives for a century.

Azurina had nine million years on Earth, and those nine million years went pleasantly untroubled by philosophy or vexing questions of life and meaning. Dead fish tell no tales, zero is our concept, and existential guilt is ours and ours alone.