Trina Higuera stands quietly on the hillside as gusts of wind bend the tall, yellowing grasses that line the dirt road. Toward the bottom of the hill, a truck loaded with 30-foot sections of redwoods revs into low gear as it struggles up the grade. Higuera’s eyes are trained on the opposite side of a small valley, where, in past centuries, her ancestors hosted large gatherings among the oak-shaded hills.

“This is where we held our Big Head,” Higuera says, referring to the ceremony that gives the place its name. In the Mutsun language, Juristac means “place of the big head,” and members of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band recognize a deep cultural and spiritual connection to the area, which lies south of the present-day city of Gilroy. Before European colonists arrived on the West Coast, powerful shamans wearing large bonnets performed ceremonies at sites throughout the roughly 64,000-acre swath of land, with crystal streams bisecting wooded hills and grassy valleys. In places near the creeks, tar bubbled from the earth.

Higuera’s great-great-great-grandmother Ascención Solórsano once resided in the area and returned to Juristac throughout her life. A revered medicine woman, Solórsano was crucial in passing on the traditional knowledge of the Amah Mutsun people. She was born as the Gold Rush attracted a new wave of American settlers to Northern California and the state government was aggressively advocating eradicating Indigenous people in the mid-1850s. Raised on a ranch near the Pinnacles, Solórsano later moved to Gilroy, gaining a reputation as a healer and humanitarian-aid provider among a tight-knit Indigenous community. Dubbed the “Saint of Gilroy,” Solórsano would treat community members’ ailments with medicinal plants she collected from Juristac and elsewhere. “Each day the sick and the lame and the afflicted came to her from hundreds of miles away,” states a 1988 article about her life published in the San Francisco Chronicle.

As one of the last surviving native speakers of Mutsun, Solórsano drew the attention of J.P. Harrington, an ethnographer from the Smithsonian Institution. Harrington visited Solórsano in 1922 and again in 1929, in the months leading up to her death. Her deep knowledge of the tribe’s material culture, cosmology, ceremonies, and place-names astonished him. Harrington’s hand-scribbled notes shed light on some of the places most important to the tribe.

“She talks about Juristac being this powerful, spiritual place,” Higuera says, referencing the Harrington notes and stories she’s heard from her elders. As she speaks, strands of hair flutter in the wind along with her half-whispered words, the drone of the approaching diesel engine growing louder.

Despite its connection to the land, the tribe has been barred from the site for generations. Some of the most important cultural sites in Juristac lie within a 5,500-acre piece of private property that has been grazed by cattle and developed for oil production over the years. An investor group now wants to build a sand-and-gravel quarry here that over its 30-year life span would gradually gouge a series of stepped, 250-feet-deep pits into the hillsides. Once every truckload of sand and rocks has been taken out of the ground, the terraced berms of the pit would encircle hundreds of acres of barren soil.

Valentin Lopez, chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, stands near Higuera along with another member of the tribe, Alexii Sigona. As Higuera speaks, Lopez focuses on the horizon to the north. His booming voice has helped lead the tribe’s campaign of opposition to the quarry project, which is undergoing an environmental review. He says that if Santa Clara County approves the mining permit, it would allow the destruction of “our most sacred site” and continue the pattern of cultural violence inflicted upon the Amah Mutsun, who were forcibly removed from their ancestral territory and, on returning to the Juristac area, were subsequently dispossessed of their land again.

The Amah Mutsun have joined with environmental groups and other supporters to rally against the proposal. In September, more than 400 people gathered at the county seat in San Jose to urge the planning commission to deny the quarry permits. Amah Mutsun singers performed ceremonial music to the beat of traditional clapper sticks to open the event, during which a tribal youth group blessed a large bundle of petitions containing more than 20,000 signatures. Many tribal members wore orange T-shirts with black lettering that read WE WILL PROTECT JURISTAC.

When the tribe attempted to deliver the signatures to county officials, the staffers in the building were reportedly unwilling to accept them at the time. Planning department staff is currently reviewing the public comments that were submitted in response to a draft environmental impact report released earlier this year. Lopez and others spent many hours raising awareness about the quarry issue, and they believe that many of the tribe’s several hundred members submitted comments opposing the project.

“During all three periods of colonization, they wanted to destroy our Indigenous knowledge, our culture, our spirituality, our environment. They wanted to destroy our people,” Lopez says, his voice rising as the logging truck nears on the narrow dirt road, its engine roaring. “If that mining permit is approved, that would be further evidence that the brutal period of destruction and domination never ended. It just evolved.”

Thousands of years ago, the ancestors of the Amah Mutsun lived in villages throughout the Pajaro River Basin, from Monterey Bay to the Diablo Mountains. They lived in dome-shaped huts made from tule and willow branches. They wove watertight baskets, ate acorns and blackberries. They hunted deer in the valleys and, when the salmon made their seasonal spawning runs, they caught them with nets and spears and fishhooks made of bone. Throughout the region, stories were told of a powerful shaman named Kuksui, who presided over a society of spiritual healers that convened amid the hills of Juristac.

The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band consists of the descendants of the Indigenous peoples who were forcibly removed from their villages by Spanish soldiers and relocated to Mission San Juan Bautista, south of Gilroy, and Mission Santa Cruz beginning in the late 18th century.

According to tribal historian Ed Ketchum—also one of Solórsano’s direct descendants—the people taken to San Juan Bautista came from 20 to 30 politically distinct groups. They were forced to work and punished for speaking Mutsun or conducting ceremonies. Spanish missionaries physically assaulted the Mutsun and unintentionally exposed them to foreign diseases, such as smallpox. By the time the mission secularized and the Indigenous people could leave in the 1830s, more than 19,000 had died at Mission San Juan Bautista.

Over the following century, the Amah Mutsun experienced waves of kidnapping and enslavement by American settlers and, during the 1850s, a state-sanctioned “war of extermination” against the Indians. The tribe’s later attempts to obtain federal recognition and secure land for a reservation were denied; it is still not a federally recognized tribe today. Without a federally recognized land base, most of the Amah Mutsun families that lived in Gilroy and the surrounding area have moved away over the years, and high housing costs have kept many of them from returning, Lopez says.

The tribe has long been working to restore many of its traditional ceremonies and land-management practices. Over the past decade, the Amah Mutsun Land Trust, a nonprofit organization led by the tribe, has engaged tribal members in land-stewardship projects, while some are reviving traditional dances. Lopez and other members envision a future in which they can bring ceremonies like the Big Head back to Juristac.

Although the tribe lacks access to the Bureau of Indian Affairs resources available to federally recognized tribes—making large tribal property acquisitions challenging—Lopez says he would like to someday see the area preserved and returned to the tribe. “We would like a tribal park on the whole of Juristac,” Lopez says, adding that an education center on the grounds could benefit both the tribe and the public.

Such plans would erode with an excavation of the quarry, which the tribe fears would physically and culturally damage a vital part of their aboriginal lands.

Just west of Highway 101, the Sargent Hills rise from golden grasslands that ascend toward the gnarled oak trees that top the foothills of the Santa Cruz range. Beneath the hills lies sandstone that was laid down on a Pliocene seabed millions of years ago. Sargent Creek runs through the middle of the proposed quarry site. The intermittent stream is flanked by sand and gravel that it has scoured—over thousands of years—from the hills to the north, where the larger Tar Creek serves as principal earth-mover.

The area of Sargent Ranch slated for development may not look like a particularly lucrative landscape. The property was purchased a decade ago by the developer’s parent company, the Debt Acquisition Company of America, which took control over much of the ranch after the previous owner filed for bankruptcy. The developer sees the site as a prime opportunity to provide the San Francisco Peninsula and South Bay Area with a local source of construction-grade sand—which at present the region lacks.

“The current sand needs are being met by barging in sand from Vancouver, Canada,” says Howard Justus, managing member of Sargent Ranch Partners, the San Diego–based company behind the project. He says the quarry’s close proximity to building sites would mean fewer carbon emissions would be produced in transporting the material, while safeguarding against shortages that could hamper the development of much-needed housing and infrastructure in the region.

New quarries are “incredibly hard to permit,” partly because sand is often found in riparian environments subject to strict environmental laws, Justus says. In the Sargent Hills, geologic forces have placed large volumes of concrete-grade sand on a hillside that happens to be located near a highway and a railroad line, both of which would be linked to the quarry.

“Sand is valuable because it’s difficult to mine, and we have this big supply of it,” Justus says. “And the Bay Area needs it.”

At full operational capacity, the quarry could produce up to 6,000 tons of aggregate per day. Roughly 35 million cubic yards of earth would be excavated over the life of the project. In 2021, one ton of aggregate sold for $10 in the U.S.

Justus sympathizes with the tribe’s desire to return to parts of the ranch for religious reasons, but he says the quarry would not overlap with any documented villages or archaeological remains, though he acknowledges such sites exist elsewhere on the property.

“The project is not in an area that has any tangible artifacts,” Justus says. “There is nothing significant to where the quarry is going in, and the EIR didn’t find anything significant” in the project area. The developer claims he has offered to work with the tribe on a possible solution in which the mine moves forward and the tribe somehow acquires a separate parcel on the ranch.

In an interview, Lopez says he has no intention of compromising if it means allowing part of Juristac to be destroyed. He and other members of the tribe believe the quarry site in all likelihood contains ancestral objects and, possibly, burial sites.

Given the project’s toll on the larger cultural landscape, the draft environmental impact report states, the project would have “significant and unavoidable impacts” on tribal cultural resources. The report, which evaluates potential effects on cultural resources and the environment, was released in July 2022. The county is now sifting through the roughly 7,500 comments submitted during a public comment period as it prepares its final EIR. It then goes to the planning commission for consideration. The final report “will respond to all comments received” during the comment period, according to a senior planner with the county.

Situated at the confluence of several creeks, in a valley between mountain ranges, the area is home to numerous at-risk species. The quarry site lies within a wildlife corridor that’s critical particularly for mountain lions, according to Chris Wilmers, a professor of environmental studies at UC Santa Cruz who leads the Santa Cruz Puma Project. In the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains, the grasslands provide a path for cats traveling between ranges, whether the Gabilan Range to the south or the Diablos to the east. Increased development would scare the skittish cats from moving between ranges and, over time, would reduce the genetic diversity of the Santa Cruz population, Wilmers says. Many environmental groups share that concern. The sub-population “is showing really low genetic diversity, which means allowing more connectivity in that location is really important for the long-term survival of that population,” says Tiffany Yap, a senior scientist with the Center for Biological Diversity.

Other animals whose habitat and movement would be impacted include at-risk species such as the California red-legged frog, California tiger salamander, burrowing owl, and American badger. (Reportedly the Harrington notes say that Solórsano taught him the names for a wide variety of animals, but the Mutsun word for “badger” escaped her.)

The operation would involve pumping more than 80,000 gallons of groundwater per day, according to the proposal. “That’s going to have a huge impact on the hydrology of the area,” says Alice Kaufman, policy and advocacy director with Green Foothills, an environmental nonprofit in the South Bay. A decrease in the local water table could reduce streamflow in the local creeks, potentially harming steelhead and other fish species.

Along with impacts to the environment, the EIR finds that the project may damage tribal resources in the area, including artifacts linked to a ceremonial area and a nearby village site. Construction activity could also disturb human remains, though the potential impact is deemed “less than significant” if mitigation measures are taken.

The analysis of tribal resources according to the California Environmental Quality Act often focuses on material artifacts and village sites. Lopez says that although archaeologists have documented village sites in the Juristac area, the Amah Mutsun’s ancestors created relatively few permanent structures or monuments. That presents problems for a non–federally recognized tribe attempting to prove that a place is significant, Lopez says, adding that the only written history from the period of Spanish and Early American colonization was recorded by non-Native ethnographers, who generally ignored the subject of spirituality.

“So now, when we say this is a very important spiritual site, they’ll go look at the written records and say, ‘Where does it say that?’” Lopez says. “But the early archaeologists were looking for more tangible” evidence, such as statues or pyramids. The chairman says the Amah Mutsun’s ancestors were less focused on altering the landscape than were other pre-American cultures: “Our creation story tells us that Creator made Mother Earth perfect, and it was our responsibility to maintain it as perfect … and steward it in a way that provided for all living things, and in a way that maintained the sacredness of the landscape.”

Despite CEQA’s focus on physical artifacts and remains, the law does take into account intangible cultural resources that could contribute to a site’s significance. Even so, proving the sanctity of a place to a government entity can be an uphill battle.

Alexii Sigona, a tribal member, is a doctoral student at UC Berkeley studying environmental management and land access, with a focus on Amah Mutsun peoples. He has been paying close attention to his tribe’s efforts to navigate the state’s regulatory framework, which—following the passage of Assembly Bill 52 in 2014—requires planning agencies to consult with California tribes that have cultural ties to an area proposed for development.

While Sigona questions the county’s level of authority over land management “given that there are unratified treaties and this is all unceded territory,” he says bills like AB52 represent a major advance in Indigenous peoples’ ability to bring their expertise to bear in planning decisions. Still, tribal consultation is too often a cursory, check-the-box exercise, forcing tribes to remain vigilant to ensure that the government engages in meaningful consultation.

AB52 positions state-recognized tribes as experts on the cultural resources in their respective ancestral territories and requires public agencies to consult tribal governments early in the CEQA review process. But in many cases, the state’s ambitious cultural -protection law falls short, says Lauren van Schilfgaarde, an attorney and incoming assistant professor at the UCLA School of Law.

“The law has injected tribes into a process that they always should have been part of, but simply were excluded from explicitly for centuries,” says van Schilfgaarde, a member of the Cochiti Pueblo. And because AB52 is—like many environmental regulations—a purely procedural statute, its power relies on how effectively it is “implemented by actual people,” she says, adding that planning agencies are often not accustomed to engaging with tribes.

“Tribal people are still being questioned about the authenticity of their beliefs and about whether or not they should have access to their cultural spaces,” she says. And tribes are rightfully skeptical that their appeals are being “seriously considered by a neutral authority.”

The sacredness of a landscape, though, can be impossible to explain. Sigona says that Amah Mutsun people driving on Highway 101 can look up at the Sargent Hills and feel a connection to it, despite not having set foot on the land for generations.

“These places of power still inspire people,” he says. “The well-being of Amah Mutsun people is intertwined with the well-being of this place.”

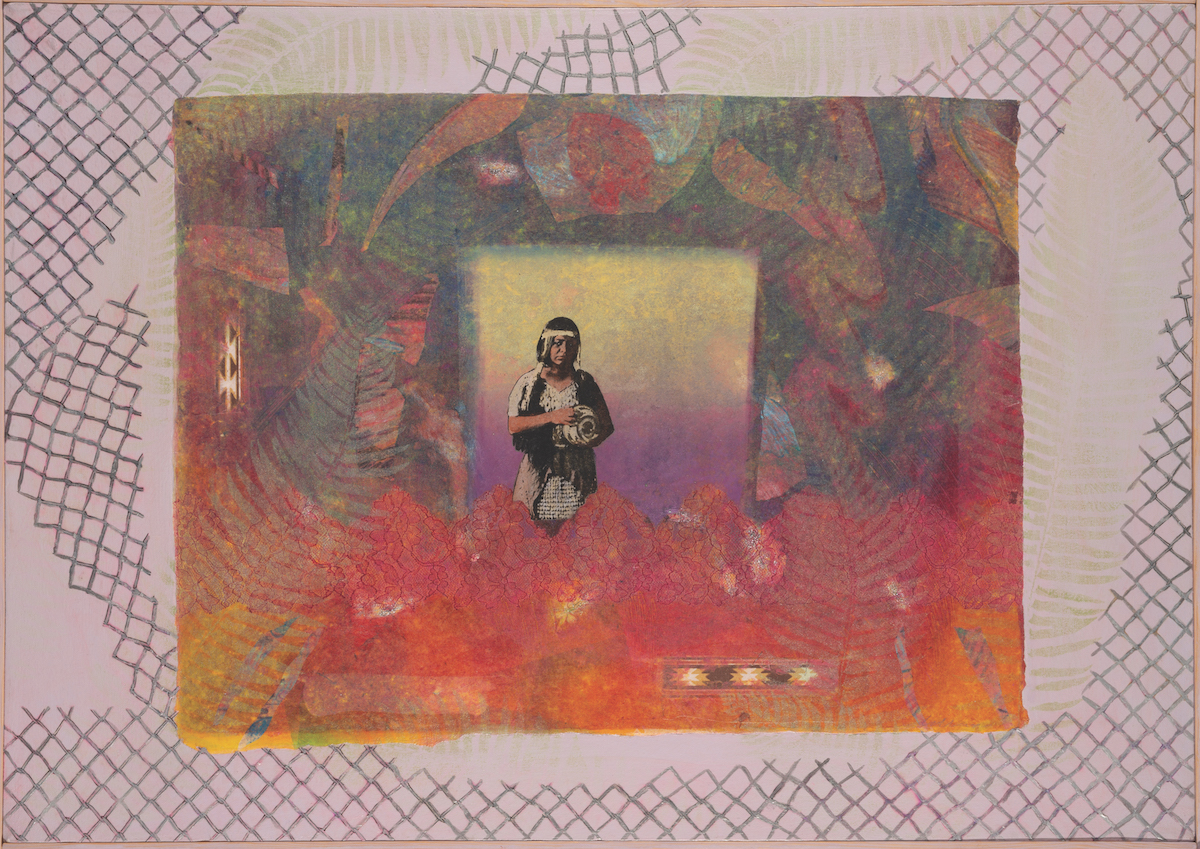

Jean LaMarr, Sacred Places Where We Pray, No. 5, 1995. Mixed media with handmade paper on canvas, 24 x 34 ½ inches. Collection of the artist.

On a bright autumn Sunday in early October, parishioners begin to gather for mass at Mission San Juan Bautista, south of Gilroy. Those who couldn’t find a seat within the 200-year-old church sit outside, beneath the pale stucco arches that line the perimeter of the mission. Built by Indigenous laborers at the edge of a low plateau, the compound overlooks a small orchard site where apple and pear trees were planted during the tail end of the mission era. A National Park Service report notes that visitors in the 1850s “commented that the pears were delicious and the apples unexceptional.”

Natalie and Gabriel Pineida sit at a picnic table a couple hundred feet from the bell tower, at the edge of a grassy plaza. The couple are both enrolled members of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, and, like most members of the tribe, have to drive a considerable distance to reach the valley, through which they used to commute regularly for work. The two now reside in Fresno with their teenage daughter.

Their journey toward understanding their Indigenous identity and relationship to Juristac began at different points in their respective lives. Natalie wasn’t aware of her Mutsun ancestry until she was a teenager.

“I thought I was Hispanic,” she says. “And then my mom brought it to my attention that we have Native in us.”

Over the following two decades, as Natalie learned more about her heritage from relatives, she has embraced the Amah Mutsun belief system and taken part in traditional ceremonies with the guidance of elders. She says reconnecting with the tribe was not always straightforward. Having been raised Catholic, Natalie has maintained many of the religious practices she grew up learning. Still, she has conflicting feelings about Mission San Juan Bautista.

She says a brief trip through the museum gift store that day elicited what she describes as “not a welcoming feeling.” Gabriel has a stronger reaction to the building.

“I don’t go in there,” he says.

Gabriel was raised knowing that he is part Native, but didn’t engage with the culture much growing up in Madera and Fresno. By the time he was a teenager, he’d had problems related to severe substance use, which he’d witnessed frequently in his household as a child. He got involved with a local gang around the same time and, over the next decade, “did a lot of bad things, and I’m not happy about it,” he says. During a particularly rough patch, Chairman Lopez, who is related to his father, suggested that Gabriel get involved with the tribe’s land-stewardship program.

He began working with the Land Trust alongside other members of the tribe, many of whom were young adults—some with similar backgrounds and recovery experiences. The Native Stewardship Corps has helped revegetate an Amah Mutsun village site called Chitactac; conducted ocean monitoring near Davenport, in the ancestral territory of the Awaswas; and practiced cultural burning in certain areas to reduce fuel for wildfires.

“I took it serious because this is what my ancestors did—maintain the land, take care of the land,” Gabriel says. “When I started coming out here, I thought, ‘Yeah, this feels right.’”

Gabriel has been in recovery for the past several years. He attributes the turnaround in his life partly to the sense of meaning he draws from his work with the tribe. “If it wasn’t for coming out here and maintaining the land, I don’t know where I’d be—maybe out there still messing up or in jail or dead,” he says.

Shadows cast by the branches of a locust tree sway across Gabriel’s orange “Protect Juristac” T-shirt. The voice of a priest, amplified by small loudspeakers at the foot of the church, fights through the wind toward the lawn, where a couple of kids have started throwing a football back and forth. Three years ago, the Spanish plaza was the starting point for the five-mile campaign march to Juristac, which the Pineidas attended with their daughter Gabriella. She also took the stage at the September protest in San Jose, saying, “Today, we have the chance that wasn’t possible for our ancestors, and that’s the right to protect Juristac.”

In the Amah Mutsun culture, tribal leaders often consider the impact of important decisions on the following seven generations of their descendants.

“It’s important that we save this place, not only for us but for our children, because, if this goes away, then it’s like erasing us—like our ancestors were never here,” Gabriel says. “And their footprints are somewhere in the dirt.”

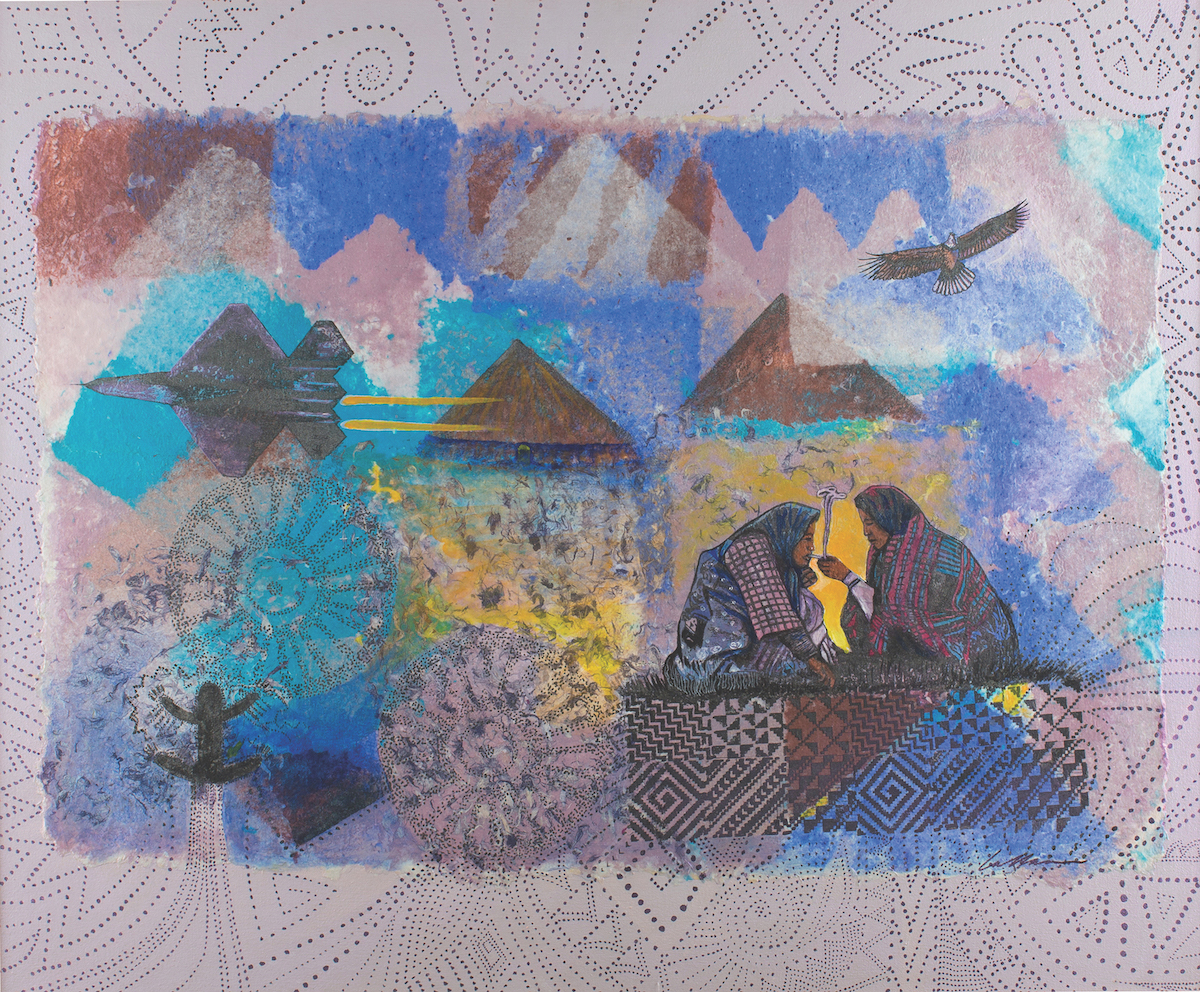

Jean LaMarr, Lighting Up, not dated. Mixed media, 44 x 36 inches. Collection of Judith

Lowry. Photograph by Akim Aginsky.

Sitting at her home in Monterey County, Higuera says that she also had a complicated sense of identity growing up. Her father rarely talked about the family’s Indigenous heritage, a reticence she attributes to the prevailing stigma attached to being a California Indian. Higuera gained more knowledge of her family’s heritage through her teenage years, but it wasn’t until her son was born that her father began speaking more openly about their Indigenous ancestry.

By the time her son Josh was a teenager, he was relaying information to her about the medicinal plants used by the tribe. “I was very proud that he was learning our history and teaching me,” she says of her son, who now works with the tribe’s plant-propagation program.

There are moments when Higuera is overcome with gratitude for her ancestors, particularly Solórsano, who—even in the twilight of her life—saw the importance of passing her knowledge on to those who would carry the culture forward.

“When I see people looking at these notes as part of our history as Mutsun people, it touches my soul because she wanted our tribe to continue on and to bring this gift to future generations,” Higuera says softly, fighting back tears. “And she’s done it.”

Support for this article was provided by the March Conservation Fund.