Text and research by Bay Nature staff

Radical Change

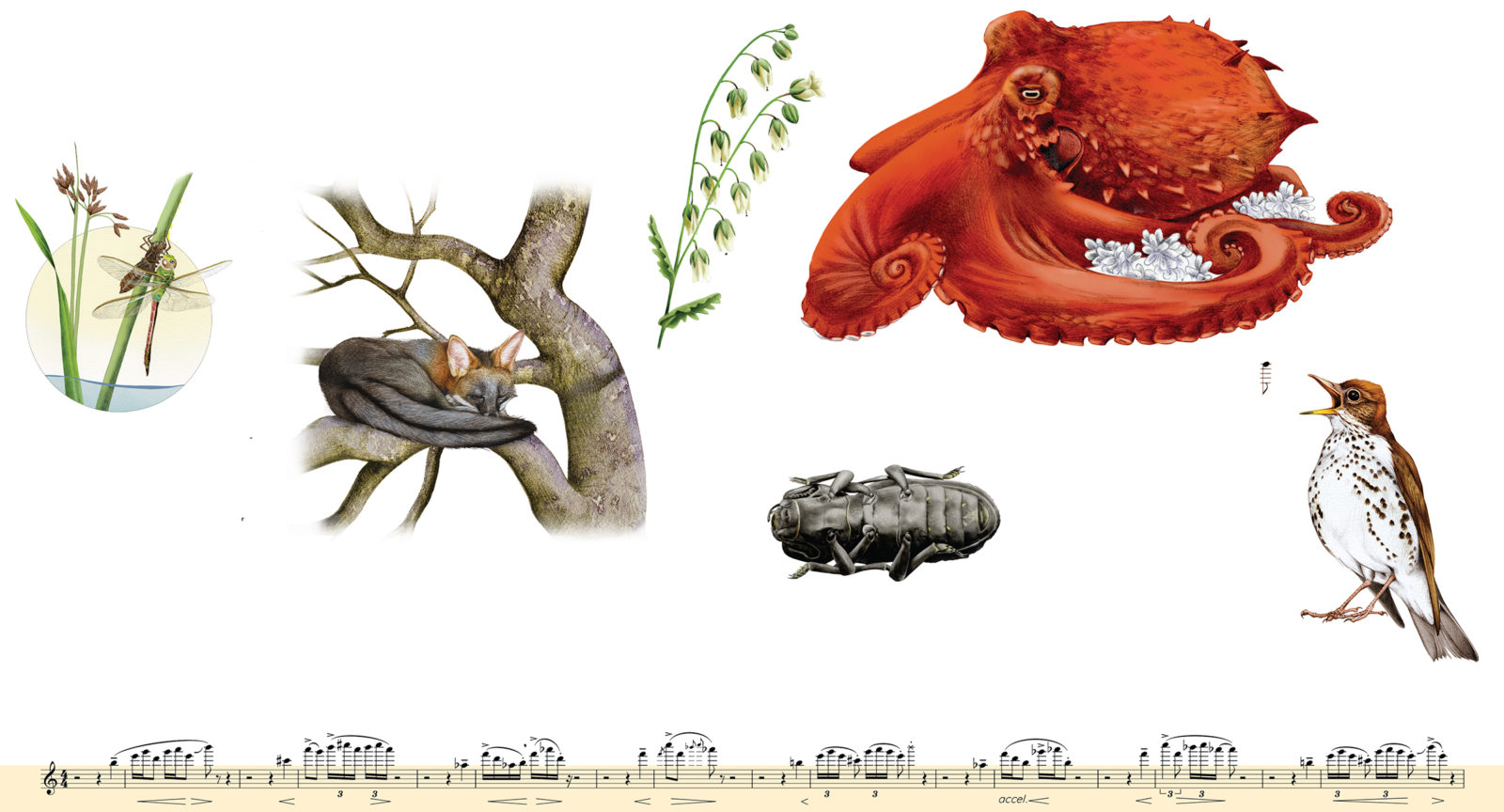

From now until late fall, you’ll be seeing common green darner dragonflies (Anax junius) around fresh water, hunting in swarms and patrolling territories more and more as the months pass. There’s a benign, sleight-of-hand reason for that sustained presence.

Born in the tropics, migrating green darners fly thousands of miles toward the Bay Area and arrive in early spring to mate and lay eggs here. Their offspring emerge as adults in late summer and fall. Meanwhile, sandwiched between the two generations, our resident green darners transform from water-dwelling creatures to air-breathing fliers in late spring.

It’s an incredible metamorphosis. At night a green darner nymph crawls from its watery home up the stalk of a tule or other water-loving plant, digs in its feet, and starts to push and arch, breaking through its own skin. A tender insect emerges and, in another hour or two, takes flight. Left behind is a translucent copy of the green darner nymph, its empty exoskeleton fixed to the tule, a kind of epitaph that reads, “Radical change happens.”

Remember to Nap

Spring is pupping time for our native gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), and a mated pair will give birth to a litter of up to seven kits. In the course of raising their young over the next nine or so months, the mother will move the den repeatedly, according to the folks at the Urban Wildlife Research Project in the South Bay, who study local gray foxes closely. Since foxes are mainly nocturnal, a good bet for catching sight of one during the day is to look up. It’s bewildering to see, but these canines can shimmy up tree trunks by rotating their wrists and extending their retractable claws. They often leap from limb to limb. Look for them napping in the crook of a branch.

The Whispering Bells

The chaparral landscapes blackened by 2020 Bay Area fires will erupt with an applause of colorful blooms this spring and next. Think of fire followers as a kind of enthusiastic crowd cheering on the return of their ecosystem. These plants, many of them native annuals, lie dormant in the soil for years until a fire jolts them to life. Then, as other species recover, the fire followers will disappear until the next burn. The seeds of whispering bells (Emmenanthe penduliflora), one of the most studied fire followers, germinate when exposed to the nitrogen oxides in charred wood and smoke. The plant’s flowers dangle like a line of handbells from its bowed stem. When dry, the papery blooms whisper a “hurrah” in the wind.

Like the Movie

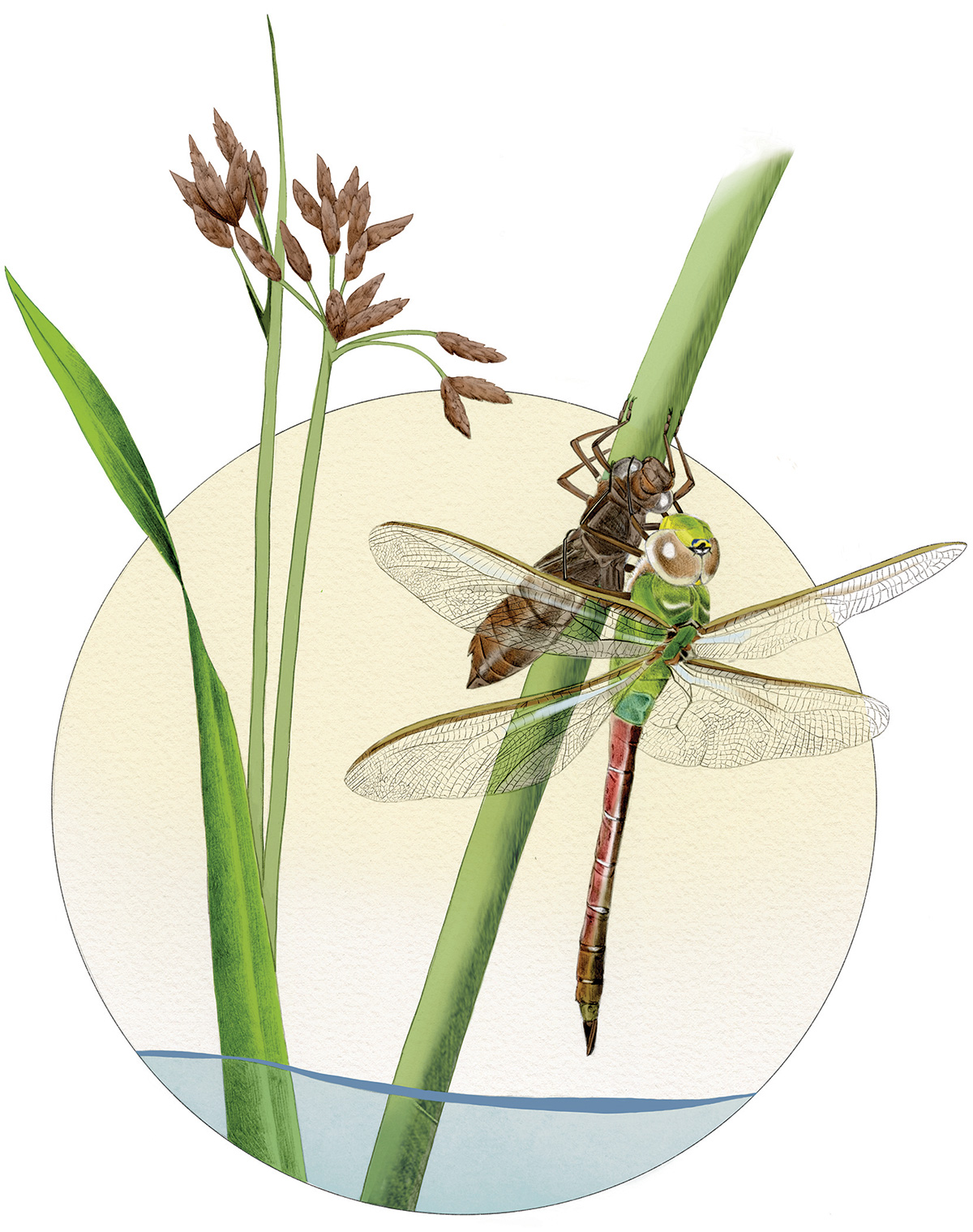

Many of us are feeling even more affection for octopuses than usual, thanks to the newish Netflix documentary My Octopus Teacher. While the common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) doesn’t live in the Pacific, we have our own intertidal species, the East Pacific red octopus (Octopus rubescens), stalking our tidepools. The red octopus is roughly the size of a large human hand, and during spring and early summer females spawn, tending their festoons of thousands of eggs in the intertidal or subtidal zones. Once the eggs hatch, the mothers die, their lives short but rich.

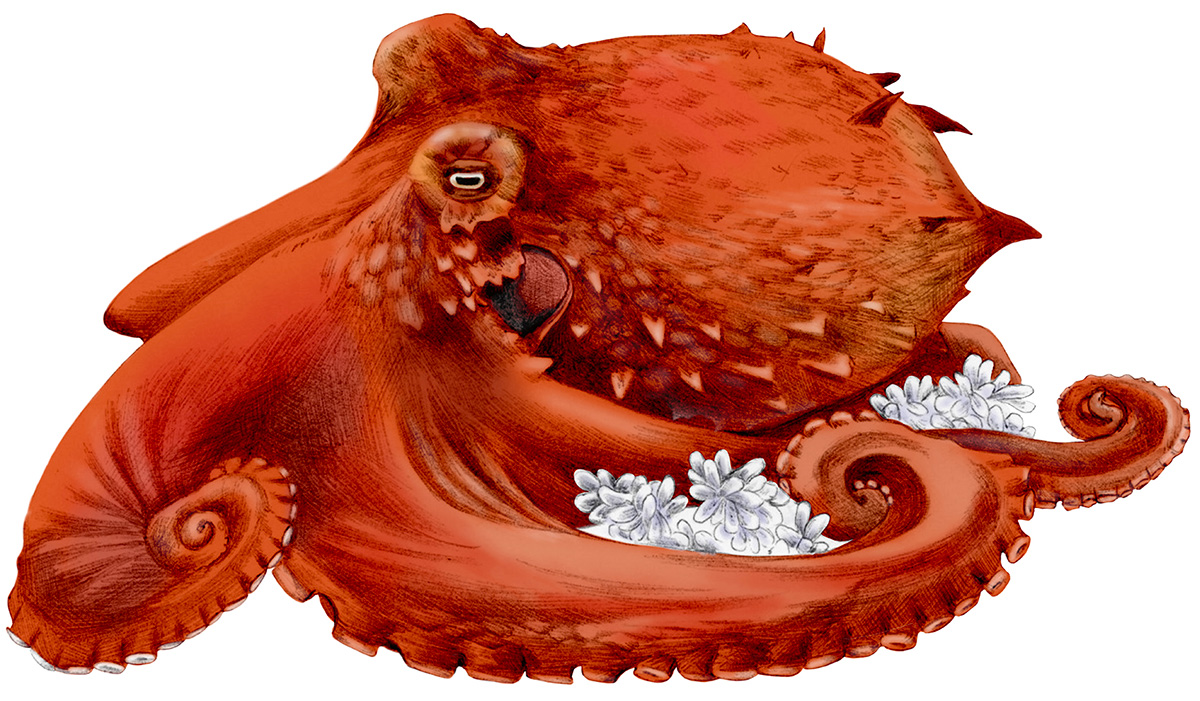

Ironclad

We’re all carrying heavy loads these days. Should you feel that the weight of yours is threatening to break you, consider the diabolical ironclad beetle (Phloeodes diabolicus). Living in the Bay Area’s woodlands, it’s a beetle that cannot fly and cannot walk particularly fast, and it tries to avert calamity by looking like a small rock or playing dead. When a predator does detect it, the diabolical ironclad beetle has a last resort. Its exoskeleton stiffens on attack, withstanding pressure 39,000 times its body weight—or, as a writer for the New York Times has calculated, “the equivalent of a 150-pound person resisting the crush of about 25 blue whales.” Researchers are hopeful that studying the exoskeleton structure could inform the creation of synthetic materials. Meanwhile, the diabolical ironclad beetle will be munching fungi that grows under the bark of oaks and cottonwoods this spring, largely lying low, relying on its super strength when it’s needed most.

Nature’s Anthem

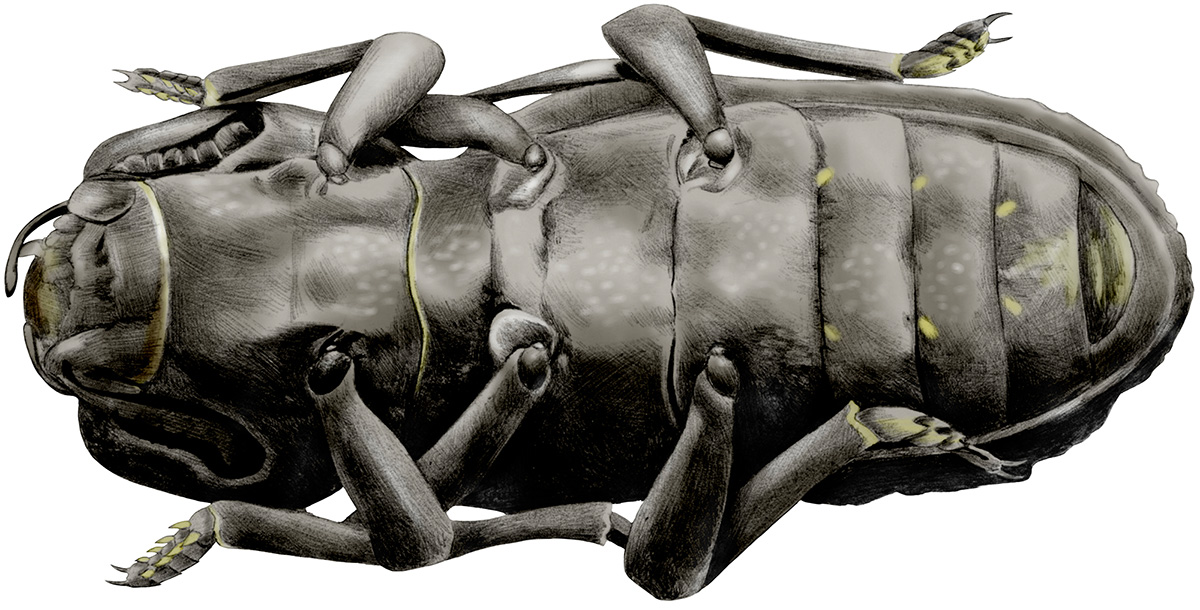

There’s a particular birdsong that has made it into umpteen poems, including one by Walt Whitman mourning the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and another by Amy Clampitt, contemplating what divides and binds us. It’s been called the most beautiful bird-music in North America. And it is here for the listening-to in Bay Area forests this spring and summer: the ethereal, harmonic notes of the hermit thrush (Catharus guttatus). It’s a song that has uplifted us during times of grief and healing for centuries.

Hermit thrush song, recorded by Richard Webster, from xeno-canto

Hermit thrush song modified and transcribed by pianist and composer Holly Mead: