n a pristine day in Monterey Bay, clear waves roll over a beach speckled with shells. Harbor seals laze on the rocks above, and a floating wary duck eyes the weekend visitors to the Hopkins Marine Station.

Stanford biologist William Gilly surveys the beach and recalls the time something weird happened here.

One day in 2012, hundreds of jumbo squid landed, circling around in the clear water and washing ashore on sand. It was a moment of divine luck and deep mystery for Gilly, who has studied the squid for 30 years.

Monterey Bay isn’t normally jumbo territory, and these ones were smaller than the 30-pounders Gilly has netted and tagged in the ocean.

For weeks, wave after wave of mini-jumbo squid made land on Gilly’s back porch. Each time, he and lab assistants would rush out to gather the wayward squid and bring them back into the lab. Each time, as he ran across the shells with the thrashing, slippery cephalopod in his arms, a new chance to wonder: what were they doing here?

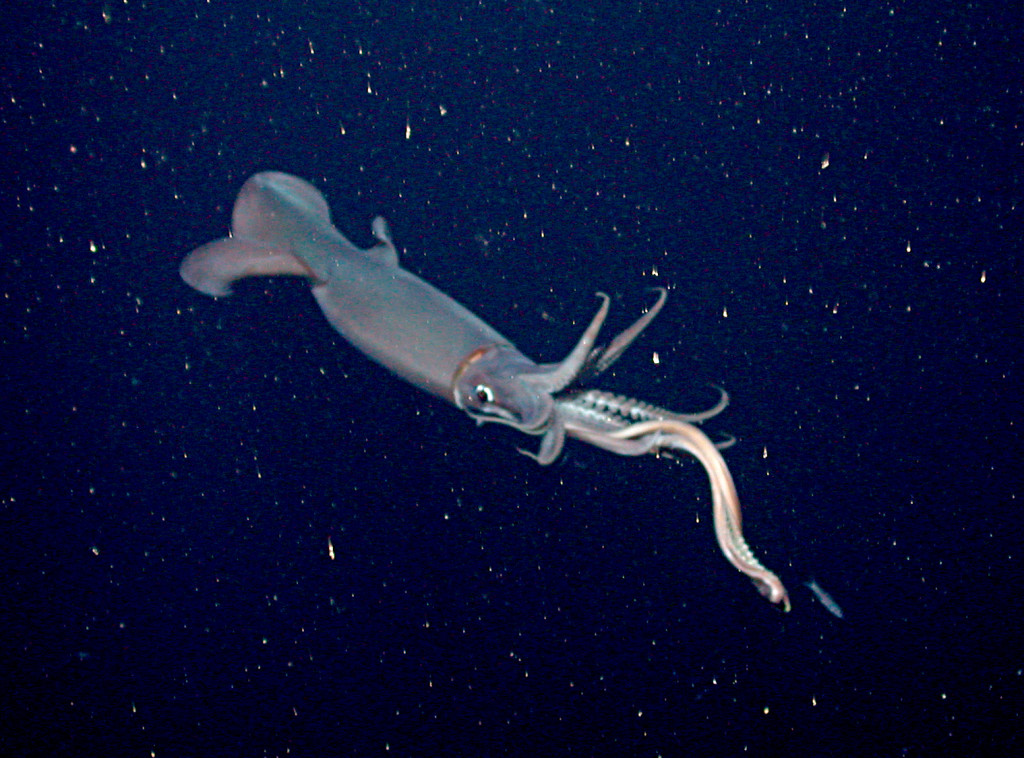

Jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas), also called Humboldt squid, are most common in the warm waters of Baja California and South America. They take their name from the Humboldt Current, which stretches from the southern tip of South America to northern Peru.

They spend most of their time in the deep ocean, where there’s not much oxygen and about as much light as a moonless night. The squid spawn in the waters of Mexico and Baja California in the winter, then migrate north in the spring and summer, up to Washington and sometimes as far as Alaska. In the fall, they return back south, but this time closer to shore. Close enough for researchers to spot them.

But new research from the Gilly lab shows that when the conditions shift against them, the Humboldt squid tend to pack up and hit the ocean currents, and ride to new territory. They follow a path of least resistance, chasing the food and thriving where their predators and competitors can’t survive. It’s either that or starve.

As a species, Dosidicus gigas is profoundly adaptable. They’re opportunistic predators, capable of taking over any niche or displacing any species that’s compromised. They even take advantage of each other: When one squid is sick or injured, Gilly said, others will eat it.

“I think the squid are always searching for something to take advantage of,” he said. “They’re like a roaming gang of bad guys.”

In 1997, California’s ecosystem was different from usual. That was an El Niño year, which over the following winter drenched the Pacific coast with rain and importantly, warmed the surface temperature of the ocean.

That was the year the squid arrived. Or rather, researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute detected the first of what would become a squid invasion in the California Current System. From San Diego to Monterey, and as far north as Alaska, fishermen were catching Humboldt squid by the ton.

The next year, as the El Niño event continued, squid sightings spiked. Then they stopped.

For four years, MBARI saw no Humboldt squid on its monthly ROV dives. The lull proved temporary. In 2002, the Humboldt squid returned, and stayed for an unprecedented eight years. During that time, researchers were wondering out loud if this time the change was permanent.

Then the sightings stopped again.

Humboldt squid appearances seemed to coincide with El Niño and La Niña events. It’s possible, Gilly said, the anomaly helped the squid move north starting in the ‘90s. In 2009, El Niño drove them away again.

“El Niño seems to be a wildcard in their ecology and it sort of resets them,” he said. “We learned some lessons from the ‘98 and 2009 El Niños. The squid react in a certain way, but that doesn’t allow you to predict where they’ll end up two years later.”

There have been pulses of Humboldt squid invading California waters since the late 1800s. For a few years in the 1930s, the invasion was so large that fisherman in Monterey Bay wanted the state to declare a bounty on the squid. The fishermen couldn’t catch their salmon and rockfish because the squid were attacking their catches on the line.

“As far as I know that was the biggest appearance in the Monterey area,” Gilly said.

It’s hard to say why they invaded back then, because there’s little El Niño information that far back, Gilly said.

It could be, Gilly said, that the squid were here all along, we just didn’t see them because they maintained a small presence lingering off the continental shelf. “We don’t know much about that area. It’s a big unknown,” Gilly said. “Open ocean is a tough, expensive place to work.”

So expansive is the ocean that we’d never know the squid were there. Until they wash ashore.

Gilly’s lab at the Hopkins Marine Station rests barely out of the shadow of the Monterey Bay Aquarium. The outside feels like a quaint waterfront park, complete with benches, a fire pit and a nearly complete view of the crescent-shaped Monterey Bay. The lab sits on a short cliff, near a tiny cove where Gilly and his dog, Charlie, mingle with lab visitors, collect shells and watch harbor seals and sea otters.

Inside, the lab is equipped with equal parts scientific instruments and squid stuff.

The walls are covered in places with thank you notes from school children, happy participants in Gilly’s Squids 4 Kids program, which sends frozen Humboldt squid to classrooms far and wide for dissection.

It’s easy to spot the theme: squid sculptures, a custom-made squid piñata, a fabric squid that zips open to reveal fabric squid guts. On the refrigerator, Gilly pointed to a refrigerator-sized Humboldt squid print made with Humboldt squid ink. “Squid are just innately weird, cool, strangely charismatic creatures,” he said.

Lately, Gilly has focused his research on electrophysiology and the squid’s ability to change color, while working to get funding for more field research on migration. Lab research on Humboldt squid is next to impossible.

In captivity, the squid get so stressed that they stop eating, or they circle their tanks and scrape up their skin. They only last a couple days. Gilly plans to raise Humboldt hatchlings in captivity to see if they respond better.

Given the challenges, in-field research is pretty much the only way to see the squid. That is, until massive numbers of squid wash up on your lab’s beach.

Gilly doesn’t quite remember whether a person or the gulls first noticed the hundreds of squid washing ashore back in 2012. But it didn’t take long.

“Hey, do you know there’s squid washing up on the beach?” Gilly recalled someone saying.

Gilly and staff could look over the bluff outside the lab, where they could see masses of the animals swimming around, some beaching themselves and some jetting back out to sea.

But these squid were different. Most of them were less than two years old and only 16-18 feet long – hardly the refrigerator-sized kraken that Gilly had spent his life tracking.

Gilly correlates the squid strandings with arriving at a place for the first time. Unfamiliar with the new waters, the squid lose their bearings and end up beaching themselves. This is usually one of the first signs of a new squid invasion.

Squid are a vanguard of climate change effects because of their fast growth and migratory nature. El Niño and climate change could lead to a permanent shift in the squid’s habitat, Gilly said.

Both El Niño and climate change mean warmer surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean. El Niño brings on a decline in ocean productivity, which affects everything from whales to seabirds. With less food in the California Current, marine animals that would otherwise eat Humboldt squid or compete with them for food generally don’t fare well.

“If conditions are disrupting the behaviors of other animals, that’s when Humboldt squid can cruise in and make the most of it,” said Julia Steward Lowndes, a former doctoral student in Gilly’s lab who co-authored a recent study with him. “They’re pretty hardy to new conditions.”

Lowndes and Gilly’s report, published in the journal Global Change Biology, concludes that changes in ocean conditions could have helped the squid find their way north.

Like the earth’s atmosphere, the ocean is made up of layers. If you dive deep enough, you’ll reach the oxygen limited zone, where fewer species live. Below that, you’ll find what’s known as the oxygen minimum zone, where there’s very little oxygen and light, but lots of pressure and weird-looking fish.

Depending on where you go, the layers’ depths vary. In general, oxygen minimum zones are becoming shallower globally in a phenomenon called OMZ shoaling. That can affect both the geographic range and depth of deep-dwelling fish, also called mesopelagic fish, also called squid food.

Humboldt squid like to hang out right where these two areas meet. That shoaling of the deep OMZ area pushes the squid food up to shallower depths, where there’s more light and more chance of a hungry, hungry Humboldt spotting them.

As you move north from Baja to California, the oxygen minimum zone generally gets shallower and begins to overlap with the photic zone. Researchers say this shoaling phenomenon has benefited predators such as squid by maximizing prime hunting water.

“Squid prefer habitat that is just barely brighter than a moonless night,” Gilly said. “That’s the sweet spot for them.”

Even with less food in their new areas, the squid could adapt one step further.

If El Niño reduces the available food in the area, the normal response is either you leave, or you stay and you die, Lowndes said.

“They sort of have a third strategy where they can stay in the area and reduce their needs, basically,” she said. “They shorten their life cycle and they reduce their size.”

The squid responded to the changing climate by maturing faster and not growing as large. They reproduced sooner, and died sooner. “They have smaller needs and smaller outputs to get them through the tighter periods,” Lowndes said.

The small jumbo squid were documented in 2010-11 in the Guyamas Basin in Sonora, Mexico, which hurt the large commercial fishery there, according to a 2013 paper co-authored by Gilly.

The Humboldt were also stunted when they washed ashore in Monterey Bay and less than two years old. That tells Gilly they were new to the area, since they hadn’t really been spotted in California for two years.

“If you wanted to list traits that make you a good invader or adaptable to climate change … you would want all the traits that Humboldt squid have,” Lowndes said. “Makes you ask why they aren’t everywhere all the time. Who knows?”

Is this an invasive species story? It is true that people didn’t directly introduce Dosidicus gigas. But you could still make the argument that if climate change drives the squid north, then humans are at least partially responsible for the invasions.

What’s the difference between migration and invasion? Humboldt squid have visited California on and off at least since the 1930s. “How often do the incursions have to be to be considered an invasion?” Gilly said. “Every thousand years? No. Every year? That’s migration.

“It seems if there’s a large predator that periodically introduces itself to an area without any relationship to seasonality, it could still be considered invasive,” he said.

There is no a periodic table of invasive species. Mercury: 62 protons. Humboldt squid: invasive.

“That’s the problem with biology, ecology,” Gilly said. “It’s messy.”

Patrick Daniel, a technician in Gilly’s lab, pulls a limp Humboldt squid out of a plastic bag. This animal was one of the ones that washed up on the beach in 2012. Frozen until 2014, the red squid now lays on a plastic tray next to a razor blade and a pair of forceps. A group of college students surround the picnic table behind Gilly’s lab. It’s unclear whether the fish smell is coming from the specimen or the ocean breeze.

Daniel squeezes the eye, and pops it out with the help of his razor blade. He shows the large, hard lens – well adapted to a dark environment.

He lifts the tentacles and shows a tiny black beak, sharp but maybe not as deadly as legend would have. It probably couldn’t do battle with a whale, but it’s perfect for eating tiny prey – and the occasional hake or salmon.

Then he hooks a finger between the squid’s body and tentacles, showing the animal’s body has two main pieces (part of its “jet propulsion” swimming style) connected by some large nerves. He slices the body open, revealing essentially a flat steak of calamari and a cluster of well-organized organs.

Daniel excises the stomach, and hold up the gritty black contents to the unblinking college students.

This squid, the one lying there thawed on a plastic tray, was just trying to find its way in a cold dark ocean. The squid who landed in Monterey came from a line of squid who were simply adapting to the climatic conditions they were handed. The invasion was neither good nor bad. It’s just the way things will be, Gilly says.

The last incursion of jumbo squid caused problems for a Washington hake fishery and can pressure the ecosystem in still unknown ways. The squid also eat salmon and rockfish, fish that humans also enjoy. But other charismatic marine animals – elephant seals, sharks and whales – eat Humboldt squid.

“Squid power is the up-and-coming thing,” Gilly said. “Squid are extremely adaptable and they’re probably going to be teaching us lessons on how to adapt to climate change and ocean change. That’s natural. There’s something to be learned there.”

With the ever-increasing chance of another El Niño beginning this summer, there’s no telling how the squid will react. Gilly says he’s given up trying to predict what they’ll do next.

If they follow the same pattern they did in Mexico years ago, they’ll have matured early at their small size, then moved their northward migration further offshore, out of the California Current System, Gilly said.

That would mean somewhere, hundreds of miles offshore, the Humboldt squid are still out there. But he won’t know until he sees them.

On a research expedition in 2010, Gilly and students were tagging large Humboldt squid in the open ocean. He and a student were trying to tag a captured squid, which had been placed in a small cooler. He reached over the squid when it latched onto his arm. He held still.

“If you infuriate them, they’ll just fight even more,” he says. “All of a sudden the cooler was full of red blood. Squid blood isn’t red, so I knew it was me.”

When Gilly freed his arm, he saw a series of little V-shaped bite marks and a “centimeter divot” missing. Now Gilly boasts to have been partially eaten by a squid. A year later, he returned the favor and published a several Humboldt squid recipes in his blog series “Squid Studies,” at Scientific American.

Humboldt squid aren’t as versatile and easy to cook as smaller, market squid. You can’t just fry up a 2-3 inch hunk of muscle, he says. Humboldt aren’t as tasty, either. “It’s like comparing pork and chicken or something,” he said.

Gilly has a background in neuroscience and physiology, and his fascination with Humboldt squid began with behavioral research. Eventually he shifted his research to the ecological side, using satellite tags to track squid migration.

In the 1980s, he went looking for them in the Gulf of California, but they proved too elusive. He gave up looking, but kept visiting the area for fishing and camping with his sons. Ten years later, they re-appeared in the Gulf. Then they showed up again in Monterey.

“Maybe they’re following me,” he said. “Maybe I can call them.”

Looking out over the cove where he first saw the squid stranding, Gilly said he did miss having them around. “It would be great to have them back.”