Since the publication of the article “Phythophthora: New Strains Breaking the Mold” in the July-September 2015 issue of Bay Nature, the San Francisco Public Utility Commission has clarified that there was a much greater infestation of a dangerous phytophthora strain in its restoration project areas than we initially reported.

Bay Nature has learned that Phytophthora tentaculata, a particularly pernicious strain of plant pathogen that has been on a federal watch list for several years, was found throughout one of the agency’s restoration sites in central Alameda County. Several of the planted seedlings date back to 2012, meaning the species could have been lurking in the soil for as long as two years. All told, a potentially lethal brew of at least six species of phytophthora have been found on the agency’s two Alameda County restoration sites, all emanating from the same native plant nursery, according to Greg Lyman, the SFPUC’s habitat mitigation engineer for the project.

Affected are not only the Alameda County sites, but also several sites on the Peninsula that the SFPUC manages. Lyman said the same nursery was growing plants for PUC restoration sites around Crystal Springs Reservoir and San Andreas Lake, but he didn’t believe any material had been yet delivered. Nevertheless, three other nursery suppliers have delivered material to those Peninsula sites and tests there revealed six other species of phytophthora, although not tentaculata.

“We have used four different nurseries for our projects and I can say I’m pretty confident that there is contamination from every one of them,” Lyman said.

The SFPUC has razed affected plants on all its sites — some 9,000 plants in the Alameda sites alone — and is continuing to heat-treat the soils, a process known as “solarization,” to get rid the pathogens. The agency has also moved to direct seeding (instead of planting nursery-raised seedlings) at these sites to avoid any more contamination. Lyman said he’s hopeful the techniques will work.

“The Alameda watershed is drier and phytophthora really need a lot of water to seed. I have confidence that with our fast action there and the way they were planted (in plastic tubes), we will be very successful,” Lyman said. “The Peninsula watershed has fog and cooler temperatures and there are places where we planted that are wetlands. I have confidence that we are going to treat these sites to the best of our ability and do our best to eradicate it. My confidence level is high, just not as high as at the Alameda watershed.”

The SFPUC is not revealing the names of the nurseries involved for privacy reasons and to avoid impugning nurseries for practices that are fairly common throughout the nursery trade. “We aren’t trying to cast aspersions on our contractors,” Lyman said. “I would say that CDFA (California Department of Food and Agriculture) is responsible for tracing it back to the nursery. We were just trying to figure out which plants we needed to treat.”

But Ted Swiecki, a consultant to the SFPUC who examined the sickly toyon plant that led to the discovery of tentaculata on the agency’s Alameda site, said he visited the nursery that harbored the tentaculata plants several years ago and noticed significant lapses in proper phytosanitary protocols. For example, container plants were low to the ground and in the “splash zone,” making it easier for phytophthora to spread through water and soil.

“There were lots of little shortcomings, but it was like pulling teeth to get anyone to do anything because they hadn’t done it before and they didn’t understand anything about plant diseases,” Swiecki said. “They didn’t understand that these were serious issues and the whole point of restoration is not to be putting exotic diseases in areas where you have native habitat. That was kind of lost on these people.”

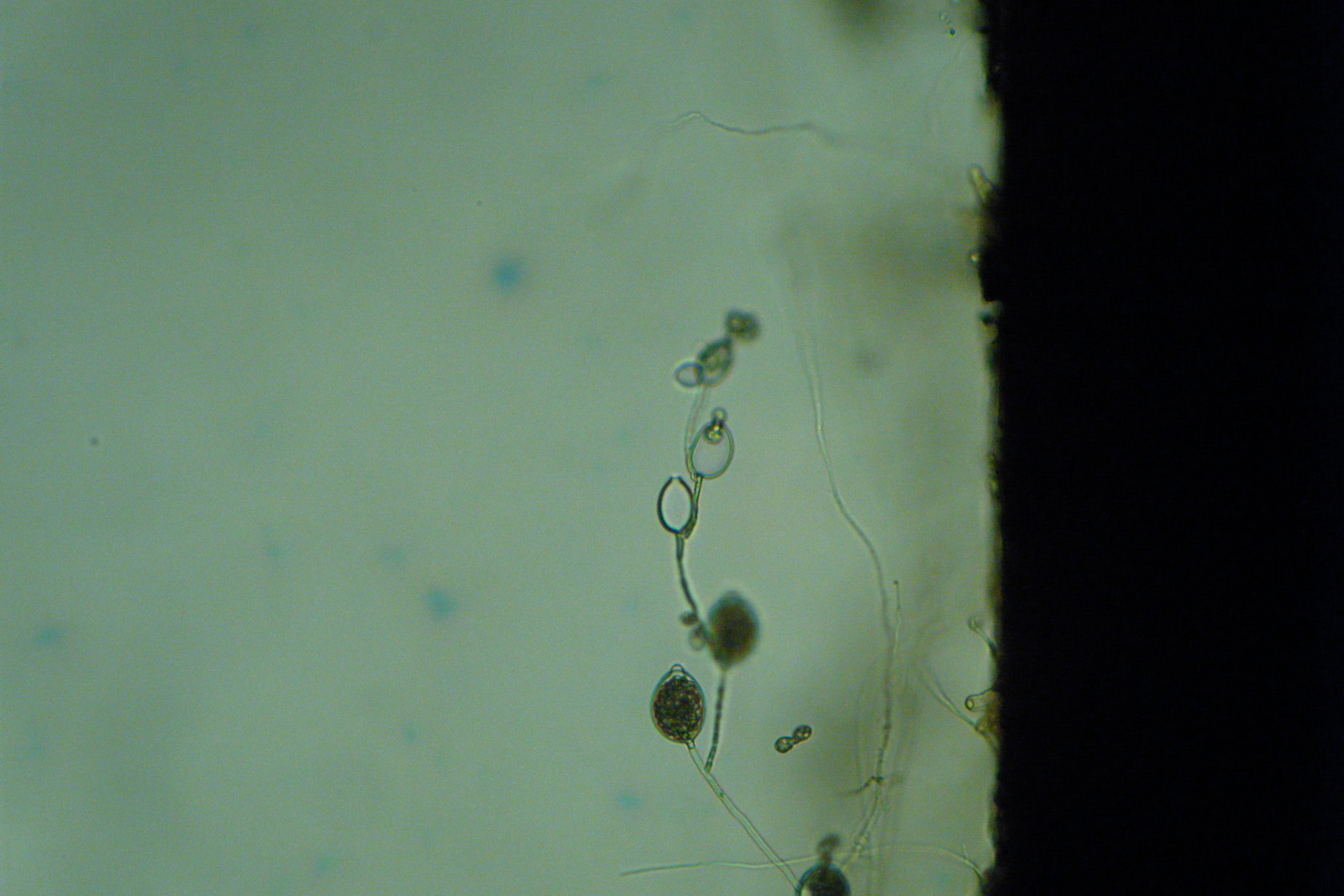

Lyman defended the agency’s use of this nursery: “We were diligent in inspecting it and the nursery was following our protocols and there were inspections before going into the ground,” he said. “The weak link is that phytophthora is microscopic and visual inspections are not adequate. We found something that didn’t look right, both above and below (the soil), and that’s what tipped us off and started a pretty extensive laboratory process.”