About 10 million years ago, something happened here in the Bay Area that must have made a big impression on the local mastodons, three-toed horses, and long-necked camels grazing on the alluvial plain that stretched east toward the young Sierra Nevada. That’s when buried magma found its way to the surface and changed the neighborhood in some fundamental ways. It was the birth of a volcano, or four, actually: a big one and three little brothers.

These days, one of those little brothers, a hill called Round Top, is the centerpiece of Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve in the Oakland hills, just south of Highway 24 and the Caldecott Tunnel. But just where was “here” 10 million years ago? In geological time hereness is relative. According to USGS geologist Russ Graymer, the triple junction of the Pacific, North American, and Gorda tectonic plates—now off the coast of Mendocino—was then somewhat south of today’s Bay Area, working its way slowly northward, as it had been for millions of years. The tremendous forces generated by the colliding plates created a zone of subsurface molten material that finally found its way to daylight. Since then, the Pacific tectonic plate, moving northward, has dragged along the resulting geologic features, like volcanoes, that are near the edge of the North American Plate. The border between the Pacific and North American plates, usually marked as the San Andreas Fault, is actually a broad zone with numerous subsidiary faults: the Hayward, the Wildcat, the Moraga Thrust, the Calaveras, and others. The farther west the volcanoes are (closer to the Pacific Plate side), the faster they move north.

- The footprints of the volcano can be read in outcrops like this, which shows basaltic lava on the right and brick-red ash on the left. These layers were once flat but have since been turned neatly vertical by tectonic forces. Photo by Scott Braley.

So our landscape gets cut up, sometimes jarring us a bit in the process. In terms of latitude, the volcanoes were born southeast of modern-day San Jose, not in Oakland. As they were being torn asunder by the Wildcat Fault, the larger, more westward vent blew its own top off and then moved farther north and now resides under Lawrence Berkeley Labs, while Round Top resides “here,” where I stand today, in Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve.

To the east of the then-active Round Top lay a vast alluvial plain where an inland ocean, known as the San Pablo Sea, had recently dried up. To the west, a range of hills rose where San Francisco Bay and the Peninsula are now. Rivers ran east down the range’s slopes, depositing millions of years’ worth of sediment in great alluvial fans. It was onto one of these fans that the volcanoes first spilled their lava, laying thick layers of molten iron-rich basalt over river sediments.

Those first moments of contact between the lava’s molten hot flow and the relatively mellow sediments were recorded in what geologists call contact zones, many of which are visible at Sibley today, baked brick-red by the action of steam and lava. Geologists find contact zones exciting, but the geologically uninclined might miss them altogether. Most of us haven’t been taught to listen to rocks very well or to interpret the stories they have to tell us about other times, and other kinds of time.

Before my recent visits to Sibley, the last time I thought so much about rocks was at Uluru, a kind of Grand Canyon in reverse that juts out of the pancake-flat central Australian desert. Uluru plays a key role in Australian Aboriginal creation stories, which unfold in a kind of alternate universe known as Dreamtime. In Dreamtime, the giant original creatures play out dramas that result in the landscapes we see today. Dreamtime is hard to grasp from a Western vantage point; but I did gather that it is longer (eternal), more significant (sacred), and more objective (real) than the ephemeral, subjective time of human experience. We are living in it, but unless we develop the sacred skills of perception, we are unable to sense it.

As I stood atop Uluru, it struck me that the notion of geologic time is not a bad secular counterpart for Dreamtime. Dramas engaging tectonic forces play out in geologic time and explain the formation of our everyday landscapes. Geologic time contains the short span of human experience, but far transcends it. And like Dreamtime, it can put our daily lives into perspective and, occasionally, can be taken to heart in a way that sheds the light of awe over the living landscape.

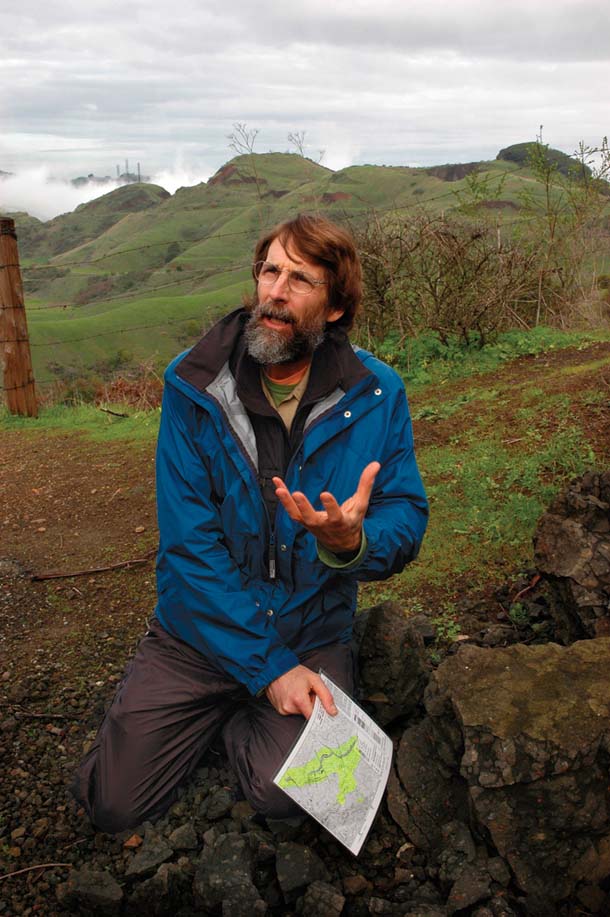

- Steve Edwards, longtime student of Sibley’s geology, holds the map of the area that he created as a graduate student in the 1980s. Photo by Scott Braley.

Until recently I was unmoved by the East Bay’s rocks. They just did not talk to me. Some were pretty, others plain, but all were dumb. I knew they had stories, but I didn’t want to hear them (unless there were fossils involved). Then I met Steve Edwards, the paleobotanist who directs the Regional Parks Botanic Garden. Rocks not only talk to Edwards, they seem to sing, and the Sibley volcanics are their Hallelujah Chorus.

In the 1970s, Edwards, then a UC Berkeley graduate student, first set about mapping the geology of these hills. Others had mapped every inch of the Berkeley hills north of Highway 24, but few had ventured south of the Caldecott Tunnel onto Sibley property, then closed, especially not the parts owned by Kaiser Sand and Gravel, which quarried here for decades. But Edwards followed the lava south and traced it back to Round Top.

The story of this volcano is a twisted one. Not only has the Pacific Plate carried it north since its birth 10 million years ago, but tectonic forces have also tipped the volcano onto its side. The geological structure that encompasses Sibley has been folded into a U by pressures from the Hayward and Moraga faults, which bracket it. The trough of the fold forms the Siesta/Gateway Valley. A geological cross section of the area looks like a many-layered taco, with the fold lying deep underground and the high edges forming the hill ridges. The once-horizontal strata of sedimentary and volcanic rocks protrude nearly vertically at the top edges of that taco, and they are now open for inspection.

The layers that make up Round Top, at the high point of this landscape, are also cut in cross section. Because the volcano is on its side, and because parts of Sibley have been gouged open by Kaiser’s quarry operations, it provides “a rare and wonderful glimpse of the inside of the upper part of a volcano, down for perhaps 1,500 feet below the old surface,” says emeritus UC geology professor Garniss Curtis.

Curtis, Edwards’ onetime academic advisor, honed his potassium-argon and argon-argon dating techniques in these hills. Those methods revolutionized geology and paleontology, giving scientists far more precise information about the age of fossils and rock strata than was previously available. It was Curtis who first dated the earliest Sibley volcanics at 10.2 million years old.

Today’s 1,763-foot-tall Round Top hill was once at the bottom of the original volcanic vent. To the south and west is evidence of a more remote past. Closest to today’s summit are Orinda Formation river gravel, sandstone, and mudstone deposited before the volcano erupted through them and lava flowed onto the older Orinda alluvial plain. Farther west, along Skyline Boulevard, are older marine rocks of the Claremont Formation.

As we set out on a walking tour of the volcano, Edwards shows me the geologic map of Sibley that arose out of his early studies. In keeping with my Dreamtime musings, his map bears a striking resemblance to Aboriginal dot paintings depicting Dreamtime characters in aerial-photography-like images that sometimes double as maps. Edwards’ chart is less colorful, but the shapes and signs representing geological formations are similarly graphic and beautiful. A stream of fluvial clastics, Orinda Formation river rocks, lies across the map like a dead serpent, cut in three places by knifelike tectonic faults. The map’s central feature: lines radiating out from a single point, forming what looks like a one-inch Star of Bethlehem. Next to it, in modest 10-point type, the map reads “vent complex” (a.k.a. volcano).

- Sibley Preserve’s striking profile is punctuated by Round Top (far right) and thick lava flows layered with bright red ash beds (near left) on the Stone Property, which will soon be open to the public. Photo by Scott Braley

.

Edwards describes Sibley as “a geological museum,” and as we walk he decodes some of the exhibits for me—starting with the basaltic dike found on Round Top itself. Basalt is the purest form of lava, a hard, dark, fine-grained material, and a “dike” is the channel feeding the volcano with molten basalt from deeper in the earth’s crust. Here on Round Top, at the East Bay Municipal Utility District’s water tank, we see a thick dike, perhaps one of the volcano’s main arteries, slicing through a sequence of less homogeneous rock—some of it tuff-breccias, created by the mixture of volcanic ash, little pieces of lava, and bits of Orinda Formation gravel all churned together and hardened into a kind of cassoulet. This material probably sloughed off the interior walls of the crater and splashed into the water and mud ponding in its cavity. Over the millennia the mud hardened into a gray mudstone, also in evidence here. Big basalt boulders lie strewn around the peak. Weathering turns them a light brownish or rusty-gray color, but beneath that thin rind they are magnificently dark: “gun steel blue,” Edwards calls it.

A few minutes later we stand above an old Kaiser Sand and Gravel quarry. From a geologist’s point of view, the decades of digging and blasting here gilded Sibley’s geological lily, providing unique views into the volcano’s heart. “Geologists love quarries, craters, road cuts, anything that exposes the earth,” says Edwards.

- The south quarry pit exposes the heart of the volcano and holds the largest of the park’s labyrinths, laid out by a local artist in 1980. Photo by Saul Chaikin.

At the edge of the quarry pit, a vertiginous spot a quarter-mile northeast of Round Top, Edwards explains that we are standing near what would have been the top of the volcano. Here the composition and shape of the original crater are visible, at least to Edwards. “What you see in the steep walls across the pit is basalt lava that filled the top of the crater and ultimately buried the vent,” he says. Since the vent has tilted over on its side, standing at this railing and looking east is like floating on your back in the original crater.

Now we are walking north on the Orinda sediments, in the direction that lava flowed out from Round Top. Racing incoming fog that threatens to obscure our views, Edwards takes long strides along the Round Top trail. An old quarry road, this trail reveals strikingly red layers of oxidized former riverbeds. Farther along, we find large sandstone blocks that are more than 65 million years old. They were torn from layers deep below the Orinda Formation by ascending lava and deposited, mixed into the basalt, on the surface. Kaiser quarrymen, who pulled massive amounts of basalt out of here to build roads and railroad bedding, left these ancient sandstone chunks behind.

At another site, Edwards identifies another intense band of red rock, this one underlying a lava flow. It is a “bake zone,” he says, caused by the lava’s own intense heat cooking the sedimentary rock below—which of course now means “beside,” since the layers are all on edge.

In the same way that flour, eggs, and milk can be baked into a creamy soufflé, spongy white bread, or rock-hard biscuits, lava can, depending on the conditions of its emergence from the earth and the ratios of its basic ingredients, be formed into all kinds of rocks. Edwards points out rhyolite tuff, a light-colored ash left from the explosion of the big brother volcano now four miles north in Berkeley; later he points out red, brain-like formations called lapilli agglomerate, lava that exploded from the volcano as hot, still-plastic cinders that fused together when they landed; and finally vesicular basalt, which is bubbly-looking lava, the pockmarks formed by gas escaping during its hardening.

There are moments as Edwards talks when I take to heart the reality of his story, when I can see before my mind’s eye, say, huge chunks of dinosaur-era stone yanked up from deep in the earth and plunked near the surface again. These moments, when I really believe our molten Dreamtime story, are thrilling. Then, as quickly as the epiphany comes, it fades and they are just rocks again.

At one point, Edwards leads us onto a closed section of the park—the Stone Property, which he says holds the best of the area’s geological exposures. Soon we stand before what may be a single thick basaltic lava flow, maybe 100 feet wide, now turned on its side and laid bare by a road that cuts right through it. It is an impressive wall of rock. I imagine it as an emission of viscous liquid formed down deep by the friction of continents colliding. While many of the basaltic flows at Sibley are punctuated by layers of volcanic ash or other configurations of volcanics, this one is pure and thick, and represents what may have been a voluminous eruption.

Nearby, Edwards points to a jumble of basaltic puzzle pieces he calls an autobrecciating basaltic flow. As lava flowed from the volcano, the surfaces in contact with earth and air cooled first, hardening before the still-hot lava center within. As that heavy inner flow kept running, it dragged the hardened top and bottom of the flow, causing them to break up. Larger chunks ground together and pulverized each other.

At exposures east of the park, where the volcanics are younger, layers of lava are interleaved with layers of sediment. Those were the quieter times between the staccato beat of dramatic eruptions, a rhythm that played out over unimaginable stretches of time—geologic time—against which the seasonal coming and going of grasses and wildflowers, and the seemingly aggressive reshaping of the land by roads and quarries, are fleeting and puny.

Whether visitors appreciate these geologic revelations or not, the quarry pits are the preserve’s most popular destination, says Park Supervisor Ed Leong. Many come to see not the volcano, however, but the very recent artifacts of the Sibley Labyrinths, several of which can be found in the preserve.

The biggest labyrinth, at the bottom of the largest quarry pit, was first laid out as an art project in 1980 by Helena Mazzariello, a local sculptor and psychic. She used to walk her goats here and would feel a “kind of magnetic force. It’s like you’re an antenna attracting energy when you’re down there,” she says. When she originally laid out the labyrinth in mud and colored powder, she expected it to last only until the first rain. But when she returned some weeks later, someone had fortified the outline with some volcanic rocks from the bottom of the quarry.

Walking the labyrinth is a kind of meditation, says Mazzariello. “I can enter with a question, and inevitably, I will emerge with some insight. It is a powerful spot.”

It surely is. Standing there, on the lip of the volcano, I try to imagine, in time-lapse animation, what I’ve learned of Sibley’s history in reverse. I ride the volcano back in time to its heyday 10 million years ago. Before I can blink, the antennae and trees covering Round Top are gone and the mountain is racing southward toward its original position in southern Santa Clara Valley. To the northeast I see the San Pablo Sea filling and the area that today comprises the San Francisco Bay rising out of the ocean to the west. As Round Top tilts back upright, the larger volcano now under the Lawrence Berkeley Labs approaches from the north, beginning to fume and spit. Suddenly, I am 45 miles south, on my back, looking out of the top of the volcano, floating on the viscous lava cooling in Round Top’s cone.

Clearly the geological Dreamtime is working for me now. Although the time travel has given me a touch of existential motion sickness, I persist with another exercise: speeding things 10 million years forward from the present. Round Top jerks northward again—geologist Russ Graymer says it’s safe to assume it will continue moving northward for quite a while. But no one knows which faults, in the long run, will inherit the burden of tectonic pressures, nor how those pressures will change over hundreds of millennia. Nor do we know what our environmental meddling will do to life here in the next century, let alone the next million years. So my imagination quickly bumps against its limits. One thing I do know, though: There are rocks 10 million years from now. And they appear to be doing fine, even singing a deep, dreamlike, and seductive song.

- Sibley Regional Preserve, home to the Bay Area’s most accessible ancient volcano, will eventually expand significantly, when the land-banked areas are opened to the public. Trail data courtesy EBRPD and USGS. Map by Rick Jonasse, Birdseye Cartography.

.jpg)

-300x199.jpg)