On a brisk afternoon in early April, I sit at my kitchen table thinking about spring. Although the vernal equinox occurred two weeks ago, here in Minnesota the snow has just begun to retreat. Despite the promise of lush greenery and abundant birdlife, the doldrums of April inevitably lead my thoughts elsewhere.

Today I recall a miles-long expanse of beach. Sloping sand dunes grade into a sheer, camel-colored bluff that continues as far as the eye can see. Just as I imagine the sensation of warm sandstone against my back, the phone rings. It’s my friend Gail, who has actually been on that beautiful bluff-backed beach this afternoon. “They’re here,” she tells me. I know exactly what she means. The bank swallows have returned to Fort Funston—the beach in my dreams.

Fort Funston is a 230-acre unit of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) located at the extreme southwest corner of San Francisco. My first visit here was in 1987, when, as a young San Francisco resident, I was inspired to walk the extent of the city’s coastline.

I quickly discovered that Fort Funston is not a place for creatures that prefer stability. Wind, rain, and scouring waves sculpt the shoreline, offering up a somewhat modified landscape on each visit. Periodic activity on nearby faults, such as the San Andreas just offshore, impacts the bluffs as well. The cliffs and dunes here are home to a robust plant and animal community whose residents must contend daily with a landscape in motion.

Each year since I first observed this colony, I have found myself drawn to Fort Funston to witness the swallows’ energetic rites of spring. This year my toddler and a busy teaching schedule hold me close to home. So I’m thrilled that Gail has provided a hotline to the birds’ return. “How did the bluffs fare over the winter?” I ask her. “How many birds are there? Which part of the bluff are they using?”

- When the swallows return to Fort Funston in April and May,they claim existing burrows or dig new ones, always in the softersandstone in the top layer of the cliffs. The burrows range from 12inches to as much as three feet in length. Illustration by Tim Gunther,www.gunthergraphics.biz.

“The northern colony had some significant erosion,” Gail tells me. “More than half of last year’s burrows are gone.” Given the region’s unusually high rainfall this past winter, this is no real surprise. At Fort Funston, bank swallows always dig their nest burrows in Colma Formation rocks, which form the upper layers of the bluff. These sandstones are geologically younger, and therefore softer, than the Merced sandstones on which they sit. This makes them easier for the swallows to excavate—but also more likely to slump.

The northern site is located at the end of the park closest to the Great Highway. A quick review of photographs I took last October shows close to a hundred burrows here, scattered along a 20-yard stretch of the bluff. I am sorry to hear that the site took such a hit, but I know that the exposed bluff offers up fresh, loose material for the birds to excavate—a challenge they seem to undertake with gusto.

The first birds this year chose to visit a subcolony a little farther to the south, just north of a spot called Panama Point. Observers counted 130 burrows here in 2004. Located roughly halfway between the park’s northern edge and the Daly City sewer outlet, the point consists of a jagged, gray outcrop of Merced Formation siltstone. A huge concrete-and-steel ring rests on the south side, half-buried in the sand. Built solidly atop the terrace in 1937, the ring served as a mount for Fort Funston’s largest piece of artillery—a 16-inch gun that could shoot projectiles as far as 25 miles out to sea.

Beginning in late March, millions of five-inch-long bank swallows undertake a 6,000-mile migration from their wintering grounds in South America. Of the few thousand that nest in California, a small proportion chooses Fort Funston.

Nesting bank swallows have two primary needs: vertical bluffs with soils friable enough to dig into (yet stable enough not to collapse easily), and ready access to freshwater habitats where flying insects are plentiful. Historically, extensive bank swallow colonies, containing thousands of breeding pairs, existed along riverbanks and at coastal river mouths throughout most of California. Today, most of the state’s bank swallows nest along the banks of the Sacramento and Feather rivers, in the Sacramento Valley. The colony at Fort Funston is one of only two or three existing coastal colonies in California—and despite its modest size (perhaps 100 pairs) it is by far the largest. Its existence is made possible by the excellent nesting habitat of the bluff and the proximity of Lake Merced, where the birds feed, just a quarter-mile east over the dunes. Bank swallows have made their home here for at least 100 years, ever since their prior feeding grounds were dried up by the 1880 damming of a stream that ran from Lake Merced to the sea along what is now Sloat Boulevard.

Many people are as devoted to this place as the swallows are. Hundreds of thousands of visitors come here annually—and a large proportion of them are locals, out hiking, birding, walking their dogs, or hang gliding. The former military base provides insight into San Francisco history, combining open space with artifacts of the city’s military past. Extensive trails meander between remnants of World War II and cold war Army installations (built to protect the city from attack by sea). The view’s not bad, either. When the fog burns off, a panorama of the coast is revealed, extending northward across the expanse of Ocean Beach and south toward Pacifica. On a very clear day, Point Reyes and the Farallon Islands appear like Avalon out of the mists.

- The bluffs above the bank swallow colony have been cordonedoff as part of an effort to restore native “dune scrub,” a treelesshabitate common to this part of the San Francisco peninsula beforeEuropean settlement. Photo by Jo-Ann Ordano.

Over the past five years, locals’ devotion has led to rancorous debate between some park visitors and officials. The dispute began in 2000 when the NPS announced the closure of acreage above the bank swallow colony in response to increased erosion rates, which endanger the birds’ habitat. Despite protests from various citizen groups seeking full access, in 2001 a judge decided in favor of the GGNRA’s authority to proceed with the closure.

Concurrently, park rangers began enforcing the National Park Service’s existing nationwide leash law. After the subsequent outcry from dog walkers, the NPS initiated a negotiated rule-making process to consider establishing approved off-leash areas at some GGNRA units. Pending that decision, dog walkers were reminded to keep their pets on leashes or risk a hefty ticket. The issue remains undecided, however. This past March, a U.S. magistrate threw out three citations, stating that the NPS had not sought sufficient public input before changing its enforcement policy. As of this writing, the NPS was appealing the decision but also continuing the negotiated rule-making process.

Closure of sections of the park is an emotional loss for those of us who freely wandered these dunes for decades. Nonetheless, increasing visitorship and faster rates of erosion do require action if we wish this site to remain intact.

The Fort Funston bank swallow colony seems tenacious, but the swallows (and all their kind in California) face a number of direct threats, habitat loss foremost among them. In a 1978 report, the California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) cited channelization of rivers (a flood-prevention technique common in agricultural areas) and the installation of erosion-controlling riprap along stream banks, as the causes of most bank swallow habitat loss. The bank swallow was listed as a California Species of Special Concern in 1979, and a 1998 DFG report indicated that the state’s population remains unstable.

Dan Murphy, former president of the Golden Gate Audubon Society, contends that the minimal development around Lake Merced and preserved open space at Fort Funston are the keys to this colony’s continued existence. NPS wildlife ecologist Bill Merkle agrees. When asked why the NPS is so determined to protect this little colony, Merkle answers matter-of-factly: “Our directive is to preserve what’s here.” That means restoration.

The exotic plant species that dominate the park today—ice plant, Monterey cypress, acacia, and eucalyptus—were planted in the 1930s to conceal military installations. Despite their attractiveness, these species—ice plant in particular—tend to crowd out natives and prevent the movement of sand that is typical for a healthy dune environment.

By contrast, native species are adapted to, and facilitate, a balanced flow of sand on dunes and bluff-tops. Photographs of Fort Funston taken prior to 1900 show a plant community called “dune scrub” growing across this section of coastline (though the adjacent, more exposed dunes at Ocean Beach may have been relatively barren). Hoping to preserve one of the habitat types native to this part of San Francisco before European settlement, botanists are currently restoring dune scrub in patches throughout the park. The 34-acre closure directly above the bank swallow colony is a major focus of this work. Notable for its lack of trees, dune scrub is dominated by low shrubs (primarily mock heather and chamiso lupine), dune grasses, herbaceous plants such as seaside daisy, coast buckwheat, and beach dune strawberry, and annuals including beach evening primrose and endangered San Francisco spineflower.

Bank swallows don’t seem to exhibit a preference for native habitat over exotic landscapes. They don’t depend on insects from the scrub community, and the twigs, leaves, or roots of native plants are no more likely to appear in nests than the dense rootlets of ice plant. Still, the benefits of the closure are significant for the nesting birds. In particular, the absence of foot traffic on coastal trails significantly reduces stress on the bluff, preventing many of the “top-down” landslides that collapse active burrows during the nesting season.

In early April, exhausted swallows begin to show up at Fort Funston a few at a time. Larger groups appear later in the month. Upon arrival, the birds zip in and out of existing burrows, repairing salvageable burrows and digging new ones. This year, by the first week of May the colony was bustling with birds. Undeterred by “damage” done by winter storms, most had set up house at the northern end of the bluff.

For male bank swallows, preparation of an attractive nest site is the prelude to courting. Using vigorous horizontal sweeping motions of his bill, the male scrapes the fine-grained rock loose then uses his feet to clear it out of the way. After a few days, he begins advertising for a mate. Sitting at the mouth of his burrow, the male fluffs up the luminous white feathers that cover his throat, sings, and flutters his wings energetically. At the sight of a passing female, he flies out and performs aerial acrobatics around the burrow to advertise his prowess and entice her to his burrow.

- During nesting season, bank swallows come and go constantlyfrom their burrows, collecting insects for their young. Photo by Robert Clay.

If she is sufficiently impressed, the female joins him in the burrow. She may make token scratches to contribute to the remaining excavation, but spends most of her time at the burrow entrance, warding off intruding swallows. When complete, the tunnel extends as much as three feet into the sandstone.

Like most songbirds, bank swallow hatchlings are blind, featherless, and utterly helpless. Within a week or so, they grow strong enough to scoot toward the tunnel mouth. This can be a risky time for the youngsters, who are easy targets for predators. Gopher snakes may slip into the burrow from above or below. American kestrels can easily reach into a burrow and scoop up defenseless babies. Ravens are another potential predator, taking adult swallows as well as the young.

For several weeks, the search for food dominates the parents’ time. Fort Funston’s bank swallows depend almost entirely on Lake Merced as a source of food. Insects are caught in flight and pressed into a marble-like bolus in the swallow’s cheek. A single bolus holds about 60 insects, and each parent makes upwards of 60 food deliveries daily—that’s 7,000 insects per pair, not including what the parents eat themselves. Bees, flies, beetles, and mayflies are common on the menu, supplemented by the occasional dragonfly or butterfly.

Highly social behavior is a hallmark of the bank swallow, and it begins at an early age. Three weeks or so after hatching, the youngsters start to stretch their wings in preparation for flight. Fledgling birds forage with their parents at first, then spend more

time with other juveniles. They hunker down for the night in unoccupied burrows, gather by day in cozy groups to “chat,” and (when not feeding) practice adult social skills: preening, mock-battling, excavating burrows, and even attempting to mate. By late July or early August, the juveniles begin to depart on their inaugural migration. Leaving in small groups as their flying skills develop, they make their way slowly to wintering grounds in South America. The adults follow shortly thereafter, leaving the colony empty. With any luck, they’ll make it back again next year, many returning to the colony where they were born.

-

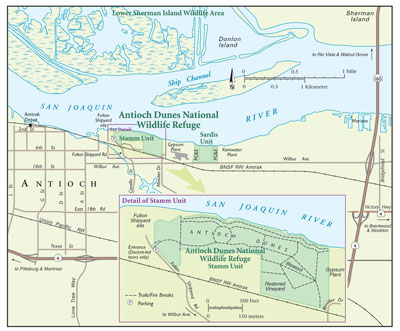

Map by Ben Pease, www.peasepress.com.

Getting there:

To see the bank swallow colony at Fort Funston, park in the southernmost parking area along the Great Highway and walk south along the beach. Alternatively, park in the small lot near the intersection of Skyline and John Muir Drive. Follow the horse trail north along the ridge and down to the beach at the Great Highway. From the main parking lot off Skyline Boulevard, take the Sunset Trail or the horse trail north through the dunes past Battery Davis, then connect to the horse trail. Fort Funston is accessible by Muni bus #18.

To participate in the efforts of the Golden Gate Audubon Society and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy to restore native dune vegetation, contact Asha Setty at (415) 239-4247.

.jpg)

-300x179.jpg)

.jpg)