There are many fish here — large fish, blue water fish, fish with true piscine gravitas: yellowfin tuna, mahimahi, Galapagos sharks. But the human visitors here at the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s one-million-gallon “pelagic” (open ocean) tank have big eyes and slack jaws for one fish only: a female white shark.

“We came all the way from Ventura for this,” says Michelle Smith, who is visiting with her husband, Noah. “And I have to say, it was really worth the drive. You hear so much about them–it’s wonderful to actually see one.”

Not that the shark impresses with her size. At a few inches past five feet long, she’s a mere juvenile, not even the largest fish in the tank. But that singular blocky profile, the emblematic pattern of gray dorsal surface with white belly, the obsidian eyes that seem to suck light from the water: somehow they connect with the saurian part of the human brain, bypassing our typical aesthetic metrics. We can only be enthralled–and intimidated–by her transcendent predatory grace.

Interest in white sharks is nothing new; in Northern California they are an enduring obsession. Our coast is one of the few places on the planet where these apex marine predators remain relatively abundant–other regions include the waters off Australia and New Zealand, South Africa, and Mexico’s Guadalupe Island. Spectacular white shark attacks on elephant seals and other pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) in our waters are logged each year at the Farallon Islands and Ano Nuevo Island, and attacks on humans occur with some frequency.

- A white shark bites a seal-shaped decoy near the Farallon Islands, one of several areas where researchers tag sharks to learn more about their habits. Photo by Scot Anderson.

Despite great popular interest in white sharks–an interest that has evolved over the years from the hyperbolically inaccurate cliches of Jaws to a more nuanced appreciation–little was known of these iconic predators until recently. About all we knew for sure was that they inhabited the waters off California, preyed heavily on pinnipeds, opportunistically scavenged whale carcasses, and sometimes bit surfers and divers, apparently mistaking them for seals or sea lions.

But we didn’t know if white sharks were wholly coastal animals or if they ranged well out to sea. We didn’t know where or when they breed, their rate of growth, their abundance. Now, thanks to sophisticated telemetry technology and an ambitious tracking program, some answers are starting to emerge.

Most of the new data is coming from Tagging of Pacific Predators (TOPP), a program that began in 2000 as a part of the international Census of Marine Life. During the past decade, TOPP has deployed sophisticated satellite archival tags and sonic tags on 4,000 individual Pacific predators, including blue whales, elephant seals, leatherback turtles, black-footed albatrosses, bluefin tuna, and blue, white, mako, and salmon sharks.

Among the findings of this research: contrary to past assumptions, white sharks are not coastal homebodies. Early conclusions by TOPP scientists–published in 2002–demonstrated that white sharks are wide-ranging, venturing far into the Pacific, with one individual traveling 3,800 kilometers in 40 days to the west coast of Kahoolawe Island in the Hawaiian archipelago.

- Biologist Scot Anderson films a passing shark. Anderson is on the team that studies and tags white sharks near the Farallon Islands. Photo by Scot Anderson.

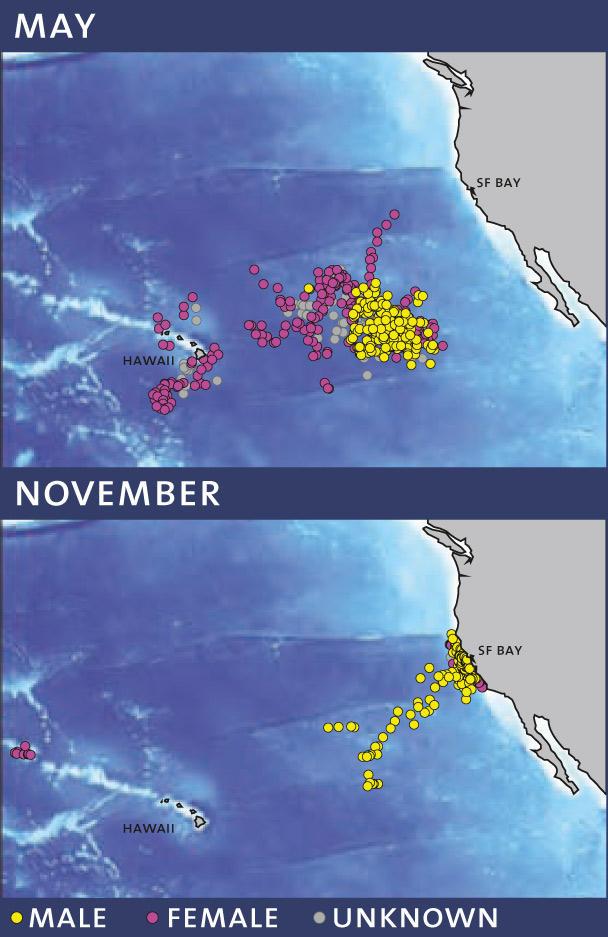

And more recent research, detailed in The Proceedings of the Royal Society in fall 2009, indicates there is a method to their wanderings. These studies, which involved more than 100 white sharks fitted with satellite tags, showed that white sharks from the California Coast and Mexico’s Guadalupe Island region converge each winter on a million-square-kilometer chunk of the Pacific, roughly equidistant from Hawaii and the continental United States, that researchers have dubbed the “White Shark Cafe.”

- Click for larger version. Dots on the map represent locations of white sharks outfitted with satellite transmitters as part of a recent study, which confirmed that the sharks are not simply coastal denizens. The study found that in winter and spring California’s white sharks congregate in the open ocean about halfway between California and Hawaii, in an area dubbed the “White Shark Cafe.” Maps modified from Jorgensen et al., Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 2009.

It’s not completely clear what they’re doing out there, says Barbara Block, a professor of marine science at Stanford University and coauthor of the recent Royal Society paper–but researchers have some ideas.

“The males that we’ve tracked seem fairly localized in the cafe region, while the females are more broadly distributed,” says Block. “There could be–with the emphasis on could–periods of overlapping between males and females that might be related to mating.”

Block noted the telemetry data logged in the pop-up tags also recorded unusual dive behavior among the sharks that might indicate foraging. The “cafe” area is not a particularly productive zone. Yet squid are known to inhabit deepwater regions throughout the world’s oceans, and white sharks could be feeding on the large pelagic fish–such as bluefin tuna–that feed on the squid.

For Sean Van Sommeran, another coauthor of the recent Royal Society paper, the findings are something of a vindication. A Santa Cruz native who is built like a roughly hewn block of granite, Van Sommeran is an anachronism in biology circles–a throwback to the 19th-century model of the gifted amateur who establishes credentials through endless field time rather than at the academy. A former commercial fisherman, he set out on long-range tuna expeditions with his father before he was 10. His first encounter with a great white shark occurred when he was 12.

“We were just coming out of the anchorage at Ano Nuevo Island,” he recalls. “We saw this big elephant seal on the surface. It was twitching and coughing blood. Then this huge white shark grabbed it, and shook it back and forth. It was like watching a T. rex feed. The skipper just laughed and kept smoking his cigarette, but I was enthralled. After that, I was completely obsessed with sharks. Still am.”

- A white shark attacks a northern elephant seal near the Farallon Islands. These enormous pinnipeds are the favorite food of white sharks. “There are a lot of calories in an elephant seal,” says one researcher, “and they float, making for easy feeding.” But any pinniped is fair game. Photo by Scot Anderson.

In 1992, Van Sommeran enlisted a few other watermen and ex-fisherman, formed an ad hoc group he dubbed the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation, and began sticking California Department of Fish and Game tags onto blue, white, and basking sharks, hoping they’d be returned if the animals were caught.

It wasn’t much, but it marked one of the first attempts to track California’s white sharks. By the late 1990s, Van Sommeran was the primary field person with a University of California at Santa Cruz project to fit white sharks with sonic transmitters around Ano Nuevo Island.

- A young sea lion with shark bite marks rests on the rocks at MossLanding on Monterey Bay. Photo by Jason Bradley/Green Stock Media, greenstockmedia.com.

“It was generally assumed that great whites were strictly coastal animals,” Van Sommeran says. “But some of the sharks we were seeing had gill net scars that could only have come from the far offshore fishery, or were tangled up with swordfish harpoon lanyards–again something they could only have encountered on the high seas. It was incredibly exciting when [TOPP’s] research confirmed what some of us suspected all along–white sharks are truly pelagic animals.”

And yet, when white sharks return from the cafe to the coast, they tend to stake out circumscribed territories, says Block. “The acoustic transmitters confirm that they’re basically sticking to base,” Block says. “The Ano Nuevo Island sharks stay mostly around Ano Nuevo, while the Farallones sharks hang generally around the Farallones. So while most or all are going to the cafe region, they return to specific areas.”

Recent acoustic array data confirmed something else: White sharks come into San Francisco Bay. “Acoustic receivers installed under the Golden Gate Bridge to monitor salmon also recorded entries by five different sharks,” Block says. “We don’t know how far into the Bay they’re going, though we could certainly find that out once we put out more receivers.”

While white sharks are a migratory species, specific populations appear to adhere rigorously to specific routes. That helps explain recent findings by one of Block’s associates, Stanford molecular geneticist Carol Reeb, who studied maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA sequences in white sharks.

“[Reeb’s data] shows that California’s white sharks compose a distinct group,” says Block. “[The sequences] suggest that the northeastern Pacific white shark population was established by a small number of sharks that probably came from the Australia/New Zealand area during the late Pleistocene–about 200,000 years ago.”

This has ramifications for white shark management, say TOPP researchers. Since northeastern Pacific white sharks do not appear to breed with other populations, they are highly vulnerable to human activity; even the inadvertent bycatch of juveniles from legal gill net fisheries could affect their numbers.

Given their top predator status, it is unlikely that eastern Pacific white shark populations were ever dense. Still, says Kevin Weng, the program manager for the Pelagic Fisheries Research Program at the University of Hawaii, it’s probable that numbers have decreased dramatically over the past century. Rrecent work by Taylor Chapple, a graduate student at UC Davis, yielded sobering estimates of just 250 mature white sharks off California today.

- Elephant seals at Año Nuevo State Reserve. Several thousand animals breed here, making this the world’s largest mainland elephant seal colony–and a rich feeding ground for white sharks. Photo by Frank S. Balthis.

“I think it’s highly likely that the era of industrial whaling–from the 1840s to the 1970s–had a huge impact on white sharks,” Weng opines. “A big part of their food source disappeared during that time–they no longer had all those [live] cetacean young and [adult] carcasses to feed on.”

- The waters off California host one of the world’s biggest populations of great white sharks. These iconic predators live large in our imaginations, but we’ve known little about their lives until recently. New studies have traced their movements along the coast, far out into the Pacific, and even into San Francisco Bay. Photo by Jason Bradley/Green Stock Media, greenstockmedia.com.

The boom in the global industrial fishing fleet that followed World War II also had profound effects, Weng says. “It is very likely there was a large unreported bycatch of great white sharks in the first decades following the war,” he says. The bycatch of juvenile white sharks in the nearshore Mexican gill net fishery remains a significant problem.

Meanwhile, white sharks continue to fascinate scientists and laypeople alike. At the top of the pelagic tank at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, out of sight of the visitors, aquarist Aaron Spotswood prepares to feed the exhibit’s star shark. He places several dead Pacific mackerel on a scale and logs their weight. The shark’s diet is carefully monitored, and the data collected on her feed conversion ratio–the specific amount of food she requires to gain weight–is yet another source contributing to the growing body of knowledge on the species.

Spotswood jams a vitamin supplement into the body cavity of one of the mackerel, and ties the fish loosely to a light cotton line; the other end of the line is fixed to a short pole. He swings the mackerel over the side of the tank and slaps it gently on the water. Below, the shark swims in broad gyres near the bottom of the tank. She seems to slowly key in on the mackerel, then abruptly darts to the surface, delicately taking the fish with an audible snap of her teeth.

Getting a great white shark to eat in captivity is no small feat, and the Monterey Bay Aquarium is writing the book on the process–and in general, on maintaining this species under captive conditions. Because great white sharks are afforded full protection by California law, the aquarium obtains its specimens under special permit after accidental captures by fishermen.

Ultimately, any stay is temporary, says Steve Vogel, the husbandry curator for the aquarium. Since 2004, the aquarium has maintained five sharks in captivity, the longest for 198 days. The most recent was released in November 2009.

Don’t expect to ever see a 20-foot, three-ton adult white shark here; the facility can only accommodate juveniles. “Even with a one-million-gallon tank, we couldn’t possibly display a mature great white shark,” Vogel observes. “Even a one-million-gallon tank would be too small.”

The aquarium’s white shark program has raised concern among some environmentalists who feel it places undue stress on the individual animals, and is inappropriate for a species so thinly distributed across its range. More to the point, the aquarium has suffered a couple of embarrassing glitches with its white sharks. In 2005, a white shark accidentally caught by a fisherman off Huntington Beach died in a small holding pen before it could be transferred to a much larger offshore enclosure. In the same year, a juvenile white shark on display at the aquarium attacked two smaller soupfin sharks, which died from their wounds.

- This 15-foot white shark was accidentally caught in a drift net off the Channel Islands and brought back to the dock in Santa Barbara. The global fishing industry is a major threat to many species of sharks, which are killed as bycatch and hunted for their fins. Photo by Tom Campbell/Green Stock Media, greenstockmedia.com.

The aquarium’s staff acknowledges these setbacks, but maintains the value of the program outweighs the risks. “About two million people have seen our white sharks,” Vogel says. “That’s more than all the people who have seen great whites in the wild throughout history. We feel our sharks are ambassadors for white sharks–for all sharks, actually. They engage people, get them aware of the conservation issues facing marine predators.”

Certainly, the public’s attitude toward white sharks has undergone a sea change since Jaws was published. Their persona has changed from insensate killer to beleaguered top predator. For that reason alone, say some researchers, any responsible program that can raise public awareness regarding white sharks–including aquarium displays or regulated cage-diving–must be considered beneficial.

“I think aquarium exhibits and shark ecotourism share a higher purpose than satisfying simple curiosity,” says UC Davis professor Peter Klimley, one of the world’s authorities on telemetry techniques for tracking large pelagic fish. “What we’re finding is that both the operators and the clients who participate (in cage diving) are absolutely militant about preserving the species. As more people see white sharks or talk to people who see them, as videos of these sightings are distributed, a large constituency is being created for their protection. The entire paradigm has changed since Jaws.”

The rapid expansion of the pinniped population off California can only be viewed as a positive development for white sharks. The fact that it is illegal to kill or take white sharks off California is also reason for modest optimism.

And as Klimley notes, the general change in public attitude toward white sharks bodes well for future conservation efforts; they are now creatures of fascination, not horror. In fact, say researchers, it should be remembered that white sharks are by no means the fiercest creatures in the sea.

Jim Tietz, a biologist with PRBO Conservation Science, spends a good deal of time at the Southeast Farallon Island lighthouse, monitoring sharks’ feeding on pinnipeds as part of a program jointly run with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. He typically spends six to ten hours a day watching for attacks during the fall–the peak of the juvenile elephant seal haul-out season. Things can get pretty busy; on one memorable day last year, researchers logged five attacks by five different sharks.

Northern elephant seals, California sea lions, Steller’s sea lions, northern fur seals, and harbor seals all frequent the islands. White sharks will attack all of them, but seem especially fond of elephant seals: “There are a lot of calories in an elephant seal,” says Tietz, “and they float, making for easy feeding.” White sharks, notes Tietz, will feed together on a single carcass, though they do not hunt cooperatively. “As far as we can tell, their only interactions are antagonistic.”

So great white sharks rule the Farallones–except when they don’t. Researchers have noted two such occasions. “Both times, an orca attacked and killed a white shark,” Tietz says. “After each attack, all the other white sharks left the area for the remainder of the season. Great white sharks are very efficient predators–but they’re not going to contest territory with an orca.”

Indeed, the larger story about white sharks is that they are, in fact, part of something larger: They are critical components in an immense wilderness where great beasts–whose lives we are only beginning to understand–still dominate.

“Just beyond the Golden Gate is an incredibly wild place,” says Block. “It’s like the Serengeti. It’s an extremely productive biological hot spot that contains these fantastic aggregations of megafauna–blue whales, humpback whales, and orcas, several species of pinnipeds, and a variety of sharks, including white sharks. The big question now is, how do we protect it.”

.jpg)