Winter can be the most peaceful time to walk on our local trails–between storms, the woods are quiet and the trails empty. But what’s that along the trailside? A skull! Coming upon an animal skull while on a hike is a genuine surprise. It might even be a little scary, but you can learn a lot from a skull. What can the bleached bones say about its departed owner? Can a few simple forensic skills help us piece together the mystery?

You may not be able to figure out how or when the critter died, but it’s relatively easy to figure out what sort of animal you are looking at. Let’s take a look at mammal skulls, since those are the ones you are most likely to see.

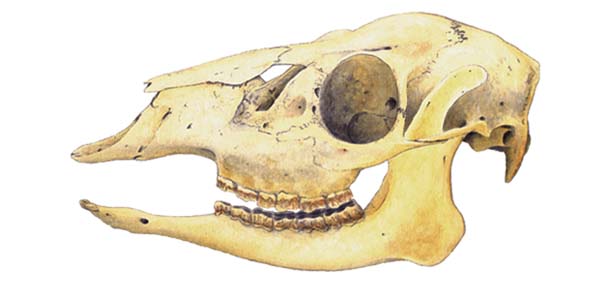

- This deer skull shows it’s also a plant eater, but deer have a bonypad on their top jaw. Illustration by Tim Gunther.

At first glance, skulls tell us if we’re seeing a meat eater, a plant eater, or an omnivore (those generalists, like us, that eat all types of foods). A plant eater, or herbivore, such as a ground squirrel or deer, has long rows of flat grinding teeth at the rear of its jaw to crush and break down tough plant fibers. The very front of the jaw has sharp incisors to cut the plants about to get ground up. Between these cutting incisors and the grinding molars is empty space. These are all the teeth you need if your diet is grass, twigs, berries, leaves, and mushrooms.

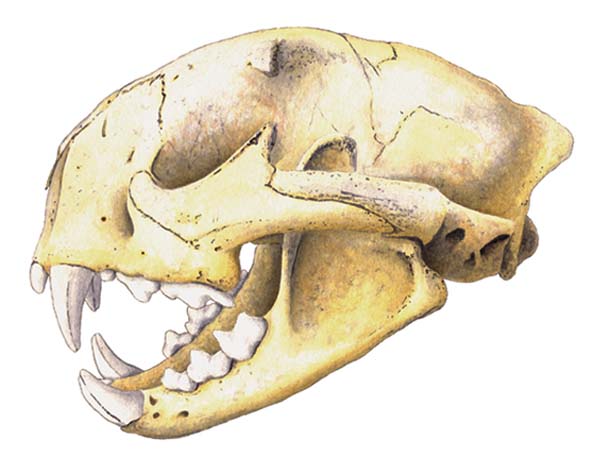

- Mountain lions have the powerful fangs and sharp cutting teeth of a carnivore. Illustration by Tim Gunther.

Meat-eating animals, carnivores, have the telltale canine teeth–fangs–to pierce tough skin and muscle. Meat eaters also have precision-cutting incisors in front, between their canines. Behind the canine teeth, where herbivores have an empty space, are sharp-edged pre-molars, flesh-tearing and large-tissue cutting tools needed by big cats. Actual molars might be very reduced or absent in strict carnivores like mountain lions, but you’ll see them in mammals–such as coyotes, bears, raccoons, and opossums–that eat a mixture of food types.

You can also learn a lot from an animal’s eye sockets–how did it see the world? Most carnivores and omnivores have eyes facing forward, like ours, giving them binocular vision, which allows good depth perception and captures sharp detail needed for hunting and capturing fast-moving targets. Herbivores have eyes that face outward to the sides, to better keep watch for predators with wide-angle, 180-degree peripheral vision.

Why are you most likely to find skulls instead of other bones? They are often left behind because there isn’t much meat on a skull for a predator or scavenger to eat. Also, they may be too big and round to be carried away.

But sometimes you’ll find other bones lying around. Look for long, skinny leg bones. If there are hooves at the end, you could be seeing deer, cow, or horse bones. Bird feet are easy to recognize, but bones with lots of toes could mean raccoon, opossum, fox, squirrel, or many other mammals.

A final clue to look for are bits of fur, feathers, skin, or scales. If there is black and white fur and a funny smell around the bones, you know you’ve found a dead skunk! Fur and feathers can help with identification, but even these little bits are food for lots of insects and may already be gone.

Should you be careful poking around dead animal bones? Sure, especially with animals that are recently dead. They might have died from disease or infection, so use caution–a stick is better than your hands–but don’t be afraid to explore.

With some cursory observational skills and an awareness of the habitat you’re in, it can be fun to unravel the mystery of the bones and learn something about the creature they once belonged to.

Get Out!

It’s hard to say when you’ll find bones along a trail. The more time you spend outdoors, the better your chances! Science museums are great places to get familiar with skeletons. At the California Academy of Sciences (www.calacademy.org), you can’t miss the blue whale skeleton, but you can also visit the Naturalist Center (10-5 daily) to check out an activity box with casts of skulls and bones. At the Exploratorium (www.exploratorium.org), the second-floor biology exhibit has beetles and other critters busily turning dead rodents and birds into skeletons. Or head over to the Lindsay Wildlife Museum (www.wildlife-museum.org) in Walnut Creek for an exhibit of raptor skulls, not to mention lots of living animals. [Dan Rademacher]

.jpg)