If the federal government abruptly filled hundreds of acres in San Francisco Bay for three new airports with no public review, today’s environmentalists would doubtless man the barricades. But some 70 years ago, local residents were far more concerned with extricating themselves and their economy from the slough of the Depression than they were with clapper rails, mudflats, and views of open water. Oakland got one airport and San Francisco two—one south of the San Mateo county line and another smack in the middle of the Bay on Yerba Buena Shoals (which came to be known as Treasure Island). All three projects—and far more—were products of a brief but epic spasm of public works initiated by the administration of President Franklin Roosevelt, who was inaugurated 75 years ago this spring. For better and worse, his New Deal radically altered Bay Area nature and the way we live, while leaving a matrix of living artifacts that we use and enjoy with little understanding of how they were created, and by whom.

In its weird gumbo of styles, Treasure Island’s buildings briefly expressed the New Deal’s hopeful and communitarian ethos. It debuted as the site of the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition, and the designers of that fair organized it around the ideal of pan-Pacific unity. The new San Francisco would, at least theoretically, learn from its oceanic neighbors, and they from it. But the fair’s real purpose was to show off a spectacular region ever more unified by federally financed technology and lifestyle amenities that would draw millions of settlers to raise real estate values and otherwise goose the local economy. Greatly expanded regional parks and opportunities for outdoor recreation would enhance the region’s appeal, and the feds provided labor and funding for those as well.

The Bay Area’s galaxy of parks, however indirectly, owes much to the men who inspired and first staffed the National Park Service after its creation in 1916. Director Stephen Mather, his assistant and successor Horace Albright, and Chief Naturalist and Forester Ansel Hall—all UC Berkeley grads—knew that the system’s remote parks had to accommodate growing leisure and automobile use that in turn would create constituents for maintenance and further expansion. At the same time, bringing in too many visitors could destroy the very qualities the parks were intended to protect. So park officials advocated a hierarchy of public spaces to take the pressure off the national “crown jewels.” That meant a generous provision for local and state parks to bridge the gap between city and national preserves while giving millions of city-dwellers access to nature.

In 1929, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.—son of the park pioneer who co-designed New York’s Central Park and created the first campus plan for UC Berkeley—published the Report of State Park Survey of California, still regarded as the gold standard of its kind and one of the most influential documents ever on state parks planning. The following year, as the Depression deepened, he and Ansel Hall produced another report recommending a 22-mile-long park chain in the East Bay hills. They suggested that such a regional park become the model for a vast ring of open spaces around San Francisco Bay.

- CCCworkers stand on a log bridge they’ve built in Mount Tamalpais StatePark. The bridge still stands today. Courtesy California State Parks,2008.

Ironically, these visionary plans might have remained only that, had it not been for the crash of 1929 and the progressive administration elected by a landslide in 1932. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his New Deal “brain trust” created two civilian labor forces to revive the economy by putting millions to work.

The Civilian Conservation Corps was the first, created by Congress in the spring of 1933 during the first frenetic weeks of the Roosevelt Administration. The CCC paid destitute young men and World War I veterans $30 a month to reclaim rural lands. Roosevelt told Congress what he hoped to achieve by creating the corps: “The overwhelming majority of unemployed Americans, who are now walking the streets and receiving private or public relief, would infinitely prefer to work. We can take a vast army of these unemployed out into healthful surroundings.” Though it was organized by the army along military lines—including barrack encampments—there was no saluting or military rank in the CCC. Moreover, CCC “boys” could leave the corps at any time. Despite the hard work, most chose to stay, attracted by the warm lodging, plentiful food, comradeship, regular income, and opportunities to learn. At the program’s peak in California, 30,000 young men worked on public lands, about 7,400 of them in state and national parks. As historian Joseph Engbeck documented in his 2002 book By the People, For the People, the state Division of Parks depended entirely on CCC labor for park development during the Depression.

The second program, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), debuted in 1935 and put millions more unemployed people back to work doing everything from laying sewer lines and building schools to conducting orchestras and painting murals. WPA employees worked mostly in cities and towns, and the CCC boys largely in rural areas, but their tasks sometimes overlapped. The WPA improved virtually every municipal park in San Francisco. Golden Gate Park owes its fly-casting ponds and lodge, horse stables, tennis courts, and model yacht club to WPA workers, who also converted a bayside dump into Aquatic Park. Elsewhere in the region, Berkeley, Oakland, and San Jose all got spectacular municipal rose gardens.

For many people, the New Deal’s vast range of initiatives was like the window of a stuffy room thrown open to sunshine and fresh air. State Librarian Kevin Starr recalled that his father spoke of those times working outdoors as among the best of his life. He and his buddies “were helping California become a better place while helping themselves move resolutely into a still uncertain future.” Ralph Anderson, who grew up near Lake Temescal Regional Park in Oakland, told me that “in retrospect, [the 1930s] seemed like a renaissance period with so many useful and handsome public facilities and buildings being built. I am sure that there was much economic distress during the period, but to me, the many civic projects brought a feeling of well-being and optimism which I have not experienced since.” Seven decades later, we are still benefiting from this renaissance and using its artifacts.

One of those is Treasure Island, from which locals and tourists alike could marvel at the two titanic bridges that had so recently ended San Francisco’s isolation at the tip of its peninsula. To the west, the locally financed Golden Gate Bridge linked the city via WPA-built approaches to the open spaces of Marin County. Closer at hand, a gracefully arched suspension span delivered cars from San Francisco directly to the fairgrounds via Yerba Buena Island before continuing on a cantilever bridge to Oakland. The Hoover Administration launched the Bay Bridge project, but it was finished under FDR in 1936. The bridge opened six months ahead of schedule after almost three and a half years of round-the-clock construction.

A year later, the Broadway Low-Level (now Caldecott) Tunnel opened up the ridges and valleys of Contra Costa County to both development and recreation. At the same time, the federal Bureau of Reclamation began construction of the Contra Costa Canal from the Delta. When it opened in 1940, the canal supplied water to industry and farming—at least until those could be replaced by more urban development.

The Olmsted and Hall report foresaw that the completion, in 1929, of the aqueduct from the Sierra Nevada to the East Bay would free the area from dependence on local creeks for water, making those protected watersheds available to the public. CCC boys at Camp Strawberry Canyon produced ten large-scale relief maps of the East Bay to help win overwhelming voter approval for the creation of the East Bay Regional Park District in November 1934. Though its initial goal exceeded 10,000 acres, the district by 1942 had acquired only 4,300 acres in what are now Tilden, Lake Temescal, Sibley, and Redwood regional parks. Still, it was a good beginning, and WPA workers built Skyline Boulevard to link three of the parks.

With CCC camps at Lake Chabot, Strawberry Canyon, Wildcat Canyon, and San Leandro, and WPA workers sent up from the flats, the new regional park district had no lack of local labor to build roads and trails, golf courses, buildings, reservoirs, and other recreational facilities, plant half a million trees and shrubs, and otherwise develop and open watershed lands for public enjoyment. As many as 3,500 young men rotated through Camp Wildcat Canyon, at the current site of the Tilden Environmental Education Center. As Eugene Swartling, who supervised the camp, recalls, “these young men were not being trained as soldiers but as good citizens; to be courteous, neat, and clean. In the evening, various classes were offered for three hours and the CCC men were encouraged to learn a trade.”

The Caldecott Tunnel facilitated access to Mount Diablo State Park, where CCC workers were building a stone lookout tower and museum at the summit. Between 1933 and 1937, CCC boys rotated between a summer camp at Calaveras Big Trees State Park in the Sierra Nevada and winter quarters at Mount Diablo. In both parks, they left their characteristic finely crafted masonry structures, including the Diablo stoves familiar to those who stay at public campgrounds improved by the CCC.

While building a park road on Mount Diablo, CCC boys unearthed an enormous tusk that UC paleontologists identified as that of a mastodon. The university sponsored WPA work to excavate other fossils near the mountain and assemble skeletons that greatly contributed to UC’s Paleontology Museum and to our knowledge of California’s prehistory.

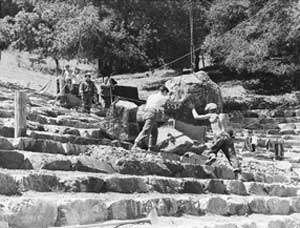

From Diablo’s summit, you could take in the extraordinary pre-smog panorama that included at least one other unit in the growing state park system. Over on Mount Tamalpais, 40 miles to the west, CCC work crews were busy building trails, bridges, roads, service buildings, fire breaks, and, on the summit, a stone fire lookout with its own water supply and telephone. Under the supervision of landscape architect Emerson Knight, they used primitive winches to partially bury lichen-encrusted boulders in a series of curved terraces to create one of the most spectacular open-air amphitheaters in the country. To accommodate the theater to its site and give it a look of hoary age, Knight ran undulating terraces around live oaks that blocked sight lines. Over 6,000 spectators at a time can enjoy a panorama of the Bay Area at least as spectacular as that from this theater’s model at Delphi in Greece (along with excellent summer theater by the Mountain Players).

- TheMountain Theater at Mount Tamalpais is one of the nation’s mostspectacular open-air theaters. CCC crews built the theater’s terracesfrom local stone hewn on site. Courtesy California State Parks, 2008.

It’s no accident that the WPA- and CCC-built structures of local rock and timber in the East Bay parks and at Mount Diablo, Tamalpais, and Big Basin state parks resemble one another and those in national parks, for they are firmly rooted in the Arts and Crafts movement that flourished earlier in the century. National Park Service architect Albert H. Good disseminated “rustic” designs in pattern books used across the country. Of those buildings he wrote, “It is a style which, through the use of native materials in proper scale, and through the avoidance of severely straight lines and oversophistication, gives the feeling of having been executed by pioneer craftsmen with limited hand tools. It thus achieves sympathy with natural surroundings and with the past.”

By today’s more ecologically informed standards, not all of the work done by the CCC and especially the WPA and another agency, the Public Works Administration, may be regarded as the “improvements” they were considered at the time. There are those bay fills under our airports, for example, and the dams such as Friant near Fresno, which destroyed salmon runs on the San Joaquin River and then the river itself. I wince at photos of hundreds of workers dumping spoils from O’Shaughnessy Boulevard into San Francisco’s Glen Canyon Park, or clearing, straightening, concreting, and burying creeks in the name of flood control. Those channelizations represented a vast federal subsidy to developers, permitting them to build up to and even over streams, with sometimes disastrous consequences for residents living along or on top of them, not to mention the species living in them.

So the New Deal’s environmental legacy is a mixed one. But without the New Deal agencies, we very likely would not have many of the parks we now take for granted, or the often elegant means by which landscape architects minimized human intrusion by, for example, artfully routing roads where they would do the least harm. Moreover, in features such as the Regional Parks Botanic Garden in Tilden Park, we can see the fledgling impetus for our current concern for native species and site-appropriate landscaping, which Olmsted senior had recommended for California during the Civil War. Garden founder James Roof used up to 300 WPA workers to build what remains Northern California’s only botanic garden devoted entirely to native plants. “The plants can’t wait,” he said at the time. “If we delay a week or two weeks, they may be gone; and when they’re gone, they’re gone forever. . . . We can’t afford to lose any more.” (At the outbreak of war, Roof was drafted and the garden was virtually lost to neglect, but a dogged Roof, with a few helpers, brought back much of the general layout and surviving plants, including the famous mountain meadow with its grove of quaking aspens.)

Well-intentioned New Deal projects such as the dams, concreted river channels, and fledgling freeways undeniably wrought long-term environmental havoc. But the public interest advocated by those such as the Olmsteds represents the window opened by the New Deal onto a world of possibilities that we have, in our oxygen-starved time, too often forgotten can be realized in short order with sufficient will and political vision. As planning historian Mel Scott has observed, “At no period prior to the thirties had the Bay Area gained so much public recreation space of regional importance as it did during that decade.” Those public lands provided the necessary nucleus for the million acres of open space now protected in the Bay Area, and a reminder of how much more will need to be protected as millions more people seek homes here. Unfortunately, though much land has been protected, we have been less willing to pay for the labor required to keep public parks healthy and vibrant.

When Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes broke ground for Friant Dam on November 5, 1939, he said, “I wonder if the people of California have not come to take the federal government too much for granted. . . . Even those of us in Washington who are responsible for carrying out orders sometimes lack comprehension of the mighty sweep of this [public works] program.” While we may now regard some “improvements” as problematic or downright disastrous, I’m afraid that we, too, take for granted the green gifts bequeathed us by a visionary administration in a time of crisis. The next time you visit a local park, pause to admire the stone masonry, the thoughtful design, and the very public nature of those preserves, and remember the minds and hands of those to whom we owe their remarkable existence.

The Living New Deal Project is a statewide collaborative effort to document, map, and interpret the public works legacy of the New Deal. If you have information or historic photographs of local projects, contact Harvey Smith: harveysmithberkeley@yahoo.com or (510)649-7395.

.jpg)

.jpg)