Every fall on the evening of the Hunter’s Moon, I join a community gathering on the summit of Mount Vision at Point Reyes to watch the large orange globe rise in the east as a bagpiper’s haunting music rises over the sound of the wind.

As dusk turns golden over the ocean horizon, Drakes Estero below us looks like the palm of a giant hand. Beckoning fingers stretch off to the east and west. Here on the peak, we stand at the very top of the watershed that feeds the biologically rich waters of the estero (the Spanish word for estuary). Remarkably, a hiker can traverse this drainage from ridgeline to ocean shore in the course of a day. Or you can easily spend many days exploring the estero up close, on foot and by boat.

Of the major estuaries along California’s coast, Point Reyes National Seashore’s Drakes Estero is among the least developed, its upper fringe traversed by just one paved road. This wild and rich convergence of land and sea, which covers 7,847 acres, is one of 29 proposed state Marine Protected Areas along the north-central coast of California. In 2012, Drakes Estero will become the only federally designated marine wilderness area on the West Coast of the continental United States–apt recognition of the estero’s status as an exceptional nursery that provides abundant food, resting habitat, and shelter for a wide array of marine organisms, from tiny sea slugs to harbor seals, leopard sharks, coho salmon, steelhead trout, and many migratory waterbirds, including brant and both species of pelicans.

All this within a 90- minute drive of downtown San Francisco.

- Harbor seals come to the estero for its protected haul-out sites near rich offshore feeding grounds. Point Reyes’s seal colonies are the largest in mainland California. Photo by Scott Doniger.

A walk to the southern end of Drakes Beach is a relatively easy way to explore the dynamic mouth of the estero, where it meets both Limantour Estero and the Pacific in ever-changing patterns of sand and water. Of the marine mammals that frequent the estero’s waters, harbor seals are the most abundant. At low tide, well over a thousand seals may haul out to rest on exposed tidal flats and sandbars in the channel. From the edge of Drakes Beach, the seals look like weathered driftwood logs. But in the water, they are in their element and they gaze back at me with large, black eyes seemingly full of curiosity.

The breeding colonies on Point Reyes are the largest in mainland California. For decades, and perhaps even centuries, the seals have been coming to the estero, where they find well-protected haul-out sites. Those protected areas are ideally located near a rich upwelling zone offshore that creates exceptional feeding conditions.

According to Sarah Allen, science adviser for Point Reyes National Seashore, 300 to 500 seal pups are born at Drakes Estero every spring. “The over-all seal population had increased in the 1980s,” she says, “but has been fairly constant over the last decade.” It’s difficult to say what that means for future population trends, but park service researchers are conducting long-term monitoring to be in a better position to analyze any future changes.

Harbor seals are considered an “apex predator” because they feed at the end of extended, complex food chains. Such predators are often used as indicators of the health of an ecosystem because they can’t thrive unless organisms at the base of that chain are also doing well.

Seals rely on undisturbed beaches for breeding, since they don’t give birth or nurse their pups in the water. The mud-flats and sandbars where these seals haul out are also crucial nursery areas. During the breeding season, females with small pups to feed and protect forage nearby, primarily inside the estero, until the pups are larger. After they are weaned, the pups feed on mysid shrimp, abundant in the nearshore waters of the bay.

- Groups of brant arrive here from southern Alaska after what can be a 60-hour nonstop flight. They flock to the estero because it has one of the healthiest populations of eelgrass in the Bay Area. Photo by Galen Leeds, www.galenleeds.net

Each night adult seals swim the esteros and Drakes Bay, hunting for herring, anchovies, sardines, rockfish, and salmon, as well as invertebrates such as octopus, squid, and crabs. Then, after hours of continuous diving and feeding, the seals need a secure place nearby to rest and get warm during the day.

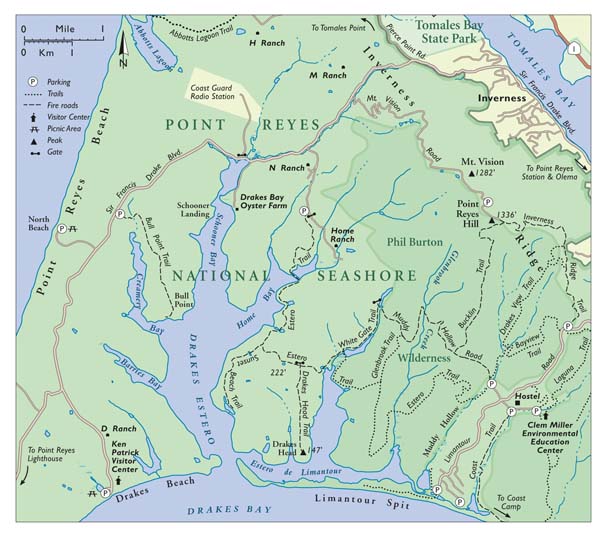

For another perspective on this dramatic meeting of land and water, you can hike out the Estero Trail to Sunset Beach or Drakes Head; I’ve walked it many times and always gained fresh discoveries and insights. However, if you take a kayak and ride the tidal currents into the heart of the estero, you’ll have one of the most rewarding experiences possible at Point Reyes, passing by swimming seals and sharks and hundreds of godwits, dunlin, and other shorebirds.

Kayakers enter and leave the estero at Schooner Bay, the northernmost of the four “finger” tributary bays joining Drakes Estero. The bay was named for boats that once transported livestock, produce, and dairy products through the estero’s narrow tidal opening to and from San Francisco. Schooner Bay’s narrow shape hints at much deeper history: The entire estero was once a network of river valleys, but rising ocean waters caused by the melting of glaciers 6,000 to 10,000 years ago inundated the valleys and created the estero. As sea level has fluctuated due to periodic global warming and cooling episodes over the last 100,000 years, the estero has gone through several periods of inundation and exposure.

On a recent kayaking trip here, I paddled away from the shore under a gray, overcast sky. A squadron of American white pelicans soared overhead, enormous birds with nine-foot wingspans. Forty or more, often joined by double-crested cormorants, may feed where the channels concentrate herring and other prey. In spring, they leave the estero, migrating inland to breed.

While onshore winds and strong tidal currents can be a challenge to paddlers, there are moments of magical tranquility and calm on the estero, when you’re able to peer deep into water that is surprisingly transparent, because so little sediment is suspended in it. Then the eelgrass beds, a major key to the estero’s productivity, are easily visible from a kayak.

Eelgrass, Zostera marina, nurtures habitat that is among the most diverse and productive ecosystems on the planet. Its roots prevent erosion by stabilizing the shoreline and its leaves trap sediment, clearing the water for increased photosynthesis. Once common in the Bay Area’s coastal estuaries, eelgrass has become increasingly rare in San Francisco Bay due to development, sedimentation, and declining water quality. The eelgrass beds in Drakes and Limantour esteros are among the healthiest in the region.

Eelgrass leaves provide a growing surface for invertebrates from barnacles to diatoms, and the beds are breeding zones for many fish, snails, worms, crabs, and other species. Nudibranchs and sea hares are common among the plant’s blades, but you’ll have a hard time seeing them, since they’re quite small and well-camouflaged in the swaying grass blades.

Healthy eelgrass beds are especially important to brant, a handsome, black sea goose with a white necklace. Brant migrate to the California coast each fall from breeding grounds in arctic breeding areas. For brant, eelgrass and its dependent invertebrates form an essential food source in southwestern Alaska, where thousands of them gather before continuing their migration. After storing up fat for the journey, the birds make an incredible 60-hour nonstop flight across the eastern Pacific to the coast of California and Mexico. And when they arrive, they once again seek out eelgrass beds.

That makes Drakes Estero crucial feeding habitat for wintering and migrant brant. From late October until early May large flocks fly over the esteros, their lines changing and remerging into loosely shaped V patterns. With the estero shrouded in a coastal fog, I have heard the gentle “cr-r-r-nk, cr-r-r-nk” calling of dozens of birds, a sound evocative of rich coastal zones.

In the first half of the 20th century, tens of thousands of brant spent winters in coastal estuaries such as Humboldt, Tomales, San Francisco, and Morro bays. Historical records document as many as 25,000 brant resting and feeding at Drakes Estero at the height of migration. San Francisco Bay hosted large numbers of brant when it had extensive healthy eelgrass beds, but by the 1960s, almost the entire population of brant that formerly wintered along the West Coast of the United States had shifted to Mexico. In Baja’s coastal lagoons, they found undisturbed feeding habitats lacking in California. Fifty years later, those areas are also threatened by increasing industrial and recreational activity. Such threats make continued preservation of Bay Area eelgrass habitats and monitoring of this charismatic goose even more important. At Point Reyes, field observers in recent winter surveys have counted as many as 1,500 brant in Drakes and Limantour esteros.

- Watch for the “wings” of bat rays breaking through the surface of the water. Photo by Scott Doniger.

The eelgrass beds provide food not just for migrating geese, but also for many other creatures that in turn feed larger predators like sharks and bat rays. On one visit to the estero’s mouth I was intently examining a rock covered with brownish-purple sea anemones when a leopard shark swam silently through the clear water just a few feet from me. Slowly but deliberately moving its head from side to side, the shark vanished into the waters of the estero as suddenly as it had appeared.

Leopard sharks, Triakis semifasciata, are part of a group called reef sharks that patrol shallow waters. Males are about three feet long, but females can be twice that. This estuary is an especially important habitat and nursery for leopard sharks, because open-water predators like sea lions don’t enter the estero, there is abundant food for the sharks, and the estero’s warmer waters accelerate growth.

In summer and early fall leopard sharks move from deeper, coastal waters into the upper parts of Drakes Estero, where they sometimes gather in the hundreds. These large congregations are thought to be feeding and possibly breeding events. Biologist Scot Anderson, who has studied sharks in the area for two decades, says that there is still much to learn about the mass gatherings of leopard sharks, even though the species itself is quite common.

Whatever the explanation for the shark aggregation, there’s no doubt that the estero is an important feeding zone for both sharks and rays. As shallow tidal water floods inland, it is warmed, stimulating these cartilaginous fish to become more active. The best time to look for the hungry, energized sharks is just before high tide, when they swim aggressively along the bottom, hunting for fish, small rays, crabs, and other bottom-dwelling invertebrates. As for the bat rays, you can sometimes see the tips of their large triangular “wings” breaking through the surface of the water, looking like pairs of miniature black dorsal fins.

But not everything nurtured by these waters is wild. Racks that support maturing oysters for the Drakes Bay Oyster Company are visible in many parts of the estero. Commercial oyster production began here in 1934 and is currently at the heart of a controversy over whether the operation’s lease should end in 2012 when the area’s wilderness designation goes into effect.

The land around the estero has been devoted to food production for quite a while. Over 150 years of cattle grazing, road building, and other activities in the watershed surrounding Drakes and Limantour Esteros have increased sediment loads and obstructed streams. The National Park Service is in the process of completing $2.44 million worth of restoration work to replace degraded stream culverts that impede fish passage. These projects and future removal of small upstream dams will help restore natural connections between upland riparian habitats and the esteros. That should in turn increase the population of steelhead and coho salmon here.

The sharks, salmon, and seals are among the most charismatic of the estero’s wildlife. But many organisms in the estero are hidden and rarely seen. A bucketful of mud contains innumerable bacteria, protozoa, worms, and crustaceans. This rich fare supports thousands of scaup, wigeon, grebes, willets, and more than 60 other species of waterbirds. These same birds abruptly scatter when a dark, rapidly flying raptor stoops at them. Peregrine falcons are magnificent predators that have rediscovered the bounty of Point Reyes after nearly going extinct. In winter, Drakes Estero hosts the continent’s highest concentration of this threatened species.

From countless invertebrates in tidal mud to swooping raptors overhead, Drakes Estero is a remarkably diverse estuary that awaits your discovery. Eel-grass is bountiful; birds migrate here to rest over the seasons; sharks, salmon, and other fish come to feed; and harbor seals birth their young. Explore this dramatic place on a short walk or a longer boating journey and its wild nature will reward you many times over.

Getting there

Take Highway 101 north to Sir Francis Drake Boulevard west. At Highway 1 in Olema, turn right and go a quarter mile to Bear Valley Road. Turn left and follow Bear Valley until it rejoins Sir Francis Drake through Inverness. To reach the Estero Trailhead, turn left about one mile after Mount Vision Road.

Responsible Kayaking

Drakes Estero is a valuable refuge for harbor seals, migrating birds, and other wildlife that find places to rest, plentiful food, and protection from ocean predators there. This also makes the estero a draw for those of us who love to observe wildlife, especially by kayak. Unfortunately, kayakers sometimes disturb the wildlife they are trying to observe. Harbor seals and migrating birds need undisturbed resting time to survive. So it’s important to follow some basic guidelines to avoid harming seals and other wildlife in the estero.

The estero is completely closed to kayakers during the seal pupping season (March 1-June 30). At all times and in all locations, federal law prohibits approaching seals closer than 300 feet. Even at greater distances, you should move away, gently, at any sign of disturbance: With seals, that means raised heads, sudden movement, or retreating into the water. With birds, watch for head bobbing, calling, flapping wings, and, of course, taking flight.

For guidelines, go to watchablewildlife.org.

.jpg)