Local organizations are scrambling to rescue their favorite state parks. Is this the dawn of a new era of cooperation or yet another sign of the decline of California’s once-proud state park system? Or both?

On May 13, 2011, the bombshell hit. For the first time ever, the state of California was going to indefinitely close 70 parks–one-fourth of the units in the system. Parks on the hit list contained prized redwood groves, ocean beaches, snowcapped peaks, fish-filled streams, and historic and archaeological treasures. But they got the ax anyway, because the state has run out of money to operate them. Northern California, with almost three-quarters of the total number of listed parks, was particularly hard hit. In the nine-county Bay Area, 18 parks were targeted for closure.

Outrage and despair were common reactions among park lovers. But a few determined advocates have gone beyond anger and begun to hammer out plans to rescue their favorite parks. Among those first in line with solid proposals are volunteers at two Bay Area parks: Henry W. Coe State Park near Morgan Hill and Jack London State Historic Park in Glen Ellen. In a few months, a nonprofit has come up with $1.2 million for Coe–more than enough to keep the 89,000-acre wilderness park open for three years with existing staff. At London, a similar group has sent the state a bid to not only finance but run the park–leading hikes and staffing the visitor center (as volunteers have been doing for years), as well as maintaining trails, cleaning bathrooms, and keeping visitors safe.

-

The future of Sonoma’s Annadel State Park remains uncertain, though the nonprofit LandPaths may take on park programming. Laura Kavanagh, closingcaliforniaparks.com.

In the past, nobody would have expected to rely on private citizens to ensure public access to Coe’s splendid swath of the inner Coast Range or to preserve the legacy of an internationally renowned author. The whole point of setting up a state park commission in 1928 was to avoid running state parks with a mishmash of boards, commissions, and agencies. State parks had value to the whole state, not just the immediate neighborhood.

-

Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods volunteers, working on a trail at Sonoma Coast State Park, may take on nearby Austin Creek State Recreation Area. Courtesy Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods.

That was then. Now, volunteer groups are providing a glimmer of hope for budget-crunched state parks around California. But there’s a dark side, too–a concern that these measures will become permanent arrangements rather than a temporary fix while the state gets its budgetary house in order. As Jack London volunteer Greg Hayes asks, “Is California becoming like a developing country, a failed state, that is bailed out by nongovernmental organizations?”

Winslow Briggs is an emeritus Stanford biology professor and member of the National Academy of Sciences. His wife, Ann, is a retired environmental information specialist. If the Briggses were trees, Winslow would be a no-nonsense alder and Ann a colorful madrone. As part of the Pine Ridge Association, each of the two has donated more than 8,000 hours of time to Henry W. Coe State Park–the equivalent of about four years of full-time work–leading hikes, planning trails, making maps, working at the visitor center, even picking up garbage. They and several dozen other volunteers are the eyes, ears, and sometimes the hands of the paid staff of the largest state park north of Los Angeles.

Winslow found the park closure announcement “ridiculous,” but he’s given up brooding in favor of getting things done. “There’s a very simple way to handle it,” he says, making a karate-chop motion with one hand. “You raise money and you give it to the state–with tight constraints. That money can only be used for Coe’s salaries and benefits. And the money the park brings in is used for operating expenses.”

Building toward this simple-sounding plan has taken two years. After a shutdown threat in 2009, the Briggses’ Pine Ridge colleague Bob Patrie came up with the idea of setting up a foundation for the park. The closure didn’t happen that year, but in February 2011, when more closures were rumored, the three of them and a few other volunteers established the Coe Park Preservation Fund. By October 2011, they had raised more than $200,000 in small donations and had secured a commitment for an additional $1 million from a group of Silicon Valley executives led by Dan McCranie, the fund’s treasurer. That’s more than enough to support the park’s existing staff of two rangers, two seasonal aides, and one maintenance person for three years, through 2014. In early December 2011, they officially signed the deal to fund park operations.

-

Sugarloaf Ridge Regional Park’s campground and volunteer-run observatory make it a popular family destination. At press time, the Sonoma Ecology Center and other groups had teamed up to take over park operations. Photo (c) Najib Joe Hakim.

Looking out at the civilized Santa Clara Valley to the west and ridge upon ridge of meadows, forests, and chaparral to the south and east, the Briggses take me for a walk in their beloved park. Along the way, they share nature lore: how Coe’s raucous acorn woodpeckers secure their nuts, how to figure out the species of an oak, how plants are responding to a recent fire. Like conscientious homeowners, they also take note of what needs fixing: a rutted trail, a junction without a trail sign, the broken hinge on an enclosed bulletin-board box.

The Briggses are deeply invested in this place, but they and the Coe Park Preservation Fund wouldn’t consider trying to run it on their own. To them, the reasons are obvious. Park staff have a campground to manage and occasionally have to deal with serious emergencies in the remote backcountry. “And we have pot farms,” Winslow says. “Several have been taken out over the years. We have off-road-vehicle trespassers. I don’t know of many park nonprofits that also include pistol-carrying law enforcement officers.”

At 1,400 acres, Jack London State Historic Park is a fraction of the size of Coe, with no campground and proportionally smaller law-enforcement and public-safety challenges. When the park’s nonprofit affiliate, the Valley of the Moon Natural History Association, heard the news about the closures, its board promptly sent a letter to the governor, secretary of resources, and head of the parks department. “Please reconsider these closures,” the group pleaded. It got no response. A month later, says association president Greg Hayes, “we talked ourselves into trying to finance and operate the park.” They were encouraged in part by Assembly Bill 42, a new law that allows the state to contract with up to 20 nonprofits to help manage threatened parks.

-

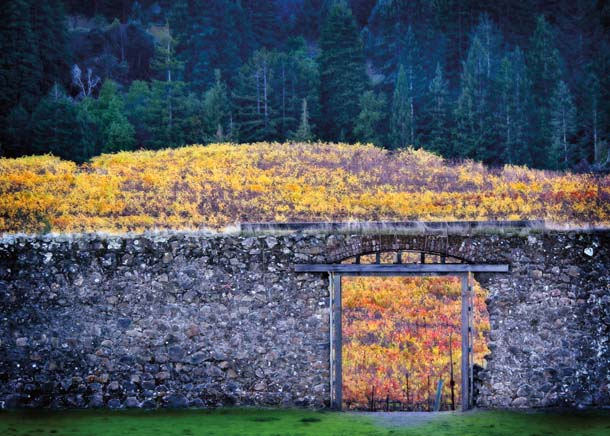

Autumn at Jack London’s historic winery, site of a successful musical theater benefit in fall 2011. Photo by Cathy Stancil, cathystancilbelleimage.com.

Hayes has the serious look of a man who knows what he’s getting into: He worked as a ranger here for 25 years. When he started in 1978, he spent his time off reading London’s work at a bookstore in Glen Ellen. Eventually, he earned a master’s degree at Sonoma State, focusing on London’s agrarian writing.

“That brought out my appreciation for London’s far-seeing intellect,” Hayes says. “He wasn’t stuck on writing about dogs in the Klondike. He was trying a noble experiment here on Beauty Ranch. He wanted ‘to make two blades of grass grow where only one has grown before.’ He wanted to do something sustainable.”

On a walk in the park, Hayes shows me the shady knoll where London first declared his intention to “set anchor” in Sonoma County. Another part of the park showcases London’s agricultural experiments, including silos, a “pig palace,” and a stallion barn. “This was the place where he experienced some of his most productive years, fulfilling his dreams,” Hayes says.

When London died in 1916 at age 40, his wife buried him here in a grave marked by a red boulder and a rickety picket fence. Down the trail next to a redwood grove are the huge stone walls of London’s mansion, Wolf House, whose innards were destroyed by a fire before he ever had a chance to live in it. “It’s a magnificent ruin, just like the end of his life,” Hayes says.

Back at the House of Happy Walls, the park museum, I pick up some “save our state parks” literature. “I’ll wait if you want to write a check,” says Hayes half-jokingly. “This is my new model!”

The association’s board has diverse talent–in addition to Hayes, there’s another retired Jack London park ranger, a local historian, a small business owner, and the former president of a major telecommunications company. But with more than a dozen buildings to maintain, 10,000 artifacts to safeguard, and 50,000 to 75,000 visitors a year, Valley of the Moon thinks it will need help. To care for artifacts, the association is asking for guidance from a state park curator. To enforce laws, it will look to state rangers in nearby parks or sheriff’s deputies.

Does Valley of the Moon think it’s up to the challenge? “Apparently so,” Hayes says with a sigh. “The alternative is abandonment.”

Valley of the Moon won’t be alone in this endeavor. It’s backed by the Parks Alliance, a Sonoma County organization that sprang into life last summer after community leaders learned that five state parks in the county were slated for closure: London, Annadel (near Santa Rosa), Sugarloaf Ridge (above Kenwood), Austin Creek (near Guerneville), and Petaluma Adobe. With start-up funds from the Sonoma Land Trust and office space from the county, the Parks Alliance is coordinating the response to the state parks crisis. So far it has taken stock of local resources, found a lead organization for each threatened park, and met monthly with partner organizations to share information and solutions.

-

Bruce Rideout in Coe State Park, helping with wildfire-recovery research coordinated by fellow volunteer Winslow Briggs. Photo by Rosemary Rideout Photography, rosemaryrideoutphotography.com.

The alliance’s deputy director and only paid staff person is community and philanthropy consultant Lauren Dixon. While Hayes seems to be embracing a new operations model out of necessity, Dixon radiates enthusiasm for locally run parks. Local control could make fundraising easier, she says, and coordination with county parks for services like, say, trash pickup and recycling could save money. “We hope to find efficiencies and create a new model for parks in Sonoma County, and throughout California.”

On October 1, a “Broadway Under the Stars” benefit put on by Transcendence Theatre Company in Jack London drew some 900 people each paying at least $35. “I’ve never been happier with my job than I was that night,” Dixon says. “Parks traditionally haven’t had events like that, but we can allow people to engage with parks in a different way–and have another set of people who support parks.”

Sixteen groups currently stand under the alliance umbrella. Three are taxpayer-supported agencies–California State Parks, Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District, and Sonoma County Regional Parks. The rest are nonprofits with a range of concerns: bicycling, horseback-riding, star-watching, trails, conservation, and education (including the Valley of the Moon association).

Among them, Santa Rosa-based LandPaths has actually been keeping the Willow Creek unit of Sonoma Coast State Park open for seven years through an innovative citizen-ranger program, with 4,000 people holding permits that show they’ve been trained to help care for the park (featured in our Oct.-Dec. 2007 issue). To LandPaths’ Craig Anderson, the key priority is working with the community around any given park: “We need to look at each site as a unique place with its own people, resources, and needs, and then develop programs for people not to just pay at a pay station but to invest themselves.”

-

A western bluebird at Petaluma Adobe State Historic Park. Photo by Eliya Selhub, closingcaliforniaparks.com.

At press time, another Parks Alliance member, Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods, was proposing to take on financial and operational responsibilities for Austin Creek State Recreation Area, just as Valley of the Moon is doing at London. The county parks department was in negotiations to finance and run Annadel with help from LandPaths. A plan for Sugarloaf Ridge, with its 49-site campground, park residences, and observatory, was being hammered out by the Sonoma Ecology Center and other organizations. A nonprofit associated with Petaluma Adobe State Historic Park was considering raising money to keep that park open. Meanwhile, the state and the alliance were facing some knotty questions: Who’s responsible for long-term maintenance? Who’s liable if the park is sued? Who’s responsible for public safety?

-

The redwood forest of Samuel P. Taylor State Park in Marin will remain open to the public thanks to an agreement with the National Park Service. Photo by Matthew Grimm.

Though Coe and Sonoma are among the leaders, park rescue efforts are also under way in Mendocino, Marin, Napa, and other counties around the state. In some places, other government agencies are rising to the challenge. Of the four state parks in Marin on the closure list, for instance, two are being rescued (for one year at least) by nearby National Park units. Point Reyes National Seashore has agreed to collect fees and retain one state employee at Tomales Bay State Park. The Park Service has agreed to add $2 to the $5 entrance fee at Muir Woods to support Mount Tamalpais State Park (which is not on the closure list, but is in the same watershed as Muir Woods) and help keep neighboring Samuel P. Taylor State Park open. The funds will even pay for more restoration work on Redwood Creek. “This won’t solve all our problems,” says Danita Rodriguez, Marin state parks superintendent. “But it’s a great start.”

Businesses are also trying to help. Lagunitas Brewing Company contacted the state about operating Samuel P. Taylor State Park, and Tomales Bay Oyster Company offered to improve and operate the Millerton Point picnic area in Tomales Bay State Park. But those businesses are being encouraged to contribute to a park contingency fund instead. “The West Marin community would like to see more of a community effort,” Rodriguez says.

The closures and other cutbacks were supposed to save $11 million in the current budget year and $22 million in the budget year 2012-13–mere “budget dust,” Hayes says, compared to $86 billion in general fund spending in 2011-2012. Over $1.3 billion in deferred maintenance is the more serious state-park financial problem. Nonprofit operators are unlikely to be able to address much of that–they’ll be too busy keeping their parks open so that they won’t deteriorate further, like foreclosed properties.

“This is and will continue to be a painful process,” state parks director Ruth Coleman told her staff in a November 3 memo. “In the short run, we are at the mercy of the present budget crisis. In the long run we must look to an enterprise model that focuses on revenue generation.” Just what that “enterprise model” might entail is the subject of heated debate inside and outside Coleman’s department. As one park superintendent jokingly told a cooperating association, “This is a great time to be selling luge rides and zip lines.”

The Briggses suggest that Californians should go back to the ballot box. While the idea of an $18 car registration fee failed in 2010, a smaller fee might succeed, they say. The state could follow the example of Montana, which earmarks $4 of each annual car registration for state parks, or Michigan, where residents can buy a $10 state parks passport sticker when they register their car.

With the recession, however, “there’s no appetite for doing that,” says Jerry Emory, the California State Parks Foundation’s communications director. “It’s totally the wrong time.”

In the meantime, volunteers such as Hayes and the Briggses are determined to do what they can. As this issue went to press, it looked as if about a dozen parks statewide had found people with enough time, money, and civic-mindedness to respond to the crisis and keep parks open.

“California is a very creative place,” Emory says. “I’m hoping that what’s going on at Coe and Sonoma can lead the way to showing what’s possible.” Otherwise, Winslow Briggs says, “we’re throwing away a legacy.”

Find ongoing coverage calparks.org, and bit.ly/spclosures.

.jpg)