Text and images by Cris Benton and Wayne Lanier

From the wetland trails near Alviso, you cannot help but notice the engineered waterscape of salt ponds and levees. Even from the air, those ponds are a South Bay signature that, along with nearby marshes, attract an amazing number and diversity of birds.

And yet, since 2006, we’ve been most interested in an area we call “the Weep,” 50 meters of humble drainage ditch. Why? Shift your view a bit from the ponds and birds, and you’ll see that there is a vibrant microbial community that contains by far the largest number of species and the greatest biomass in the salt marsh.

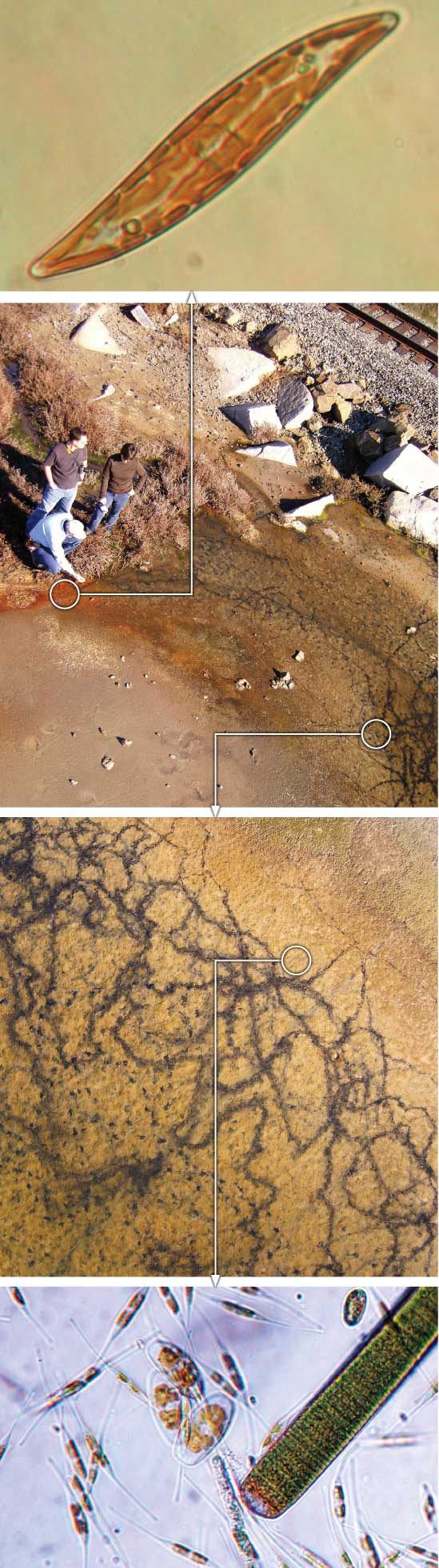

The Weep is a perfect laboratory for seeing this diversity of players at the bottom of the food chain that also drives the more visible components of the salt marsh. With images from kite-mounted cameras and field microscopes, we’ve found intricate colors and textures here that reveal microorganisms occupying habitats that vary widely over short times and distances, responding to changes in moisture and salinity. Sometimes the Weep is wet when the season has turned dry. Microorganisms abundant two months prior may have disappeared as though from a tiny Roanoke.

The Weep’s charm, particularly for those interested in microbial ecology, lies in a biological diversity that speaks to the nature of the place. Cycles of life in the Weep are principally orchestrated by water, which enters the Weep as rainfall, as runoff from higher portions of the ditch, and as seepage through flanking berms. The seepage seems to vary with tidal flow in a marsh channel immediately across the railroad tracks and with water levels in the adjacent salt ponds. As in the salt ponds, wind and sun combine to dry the Weep and increase its salinity, though not uniformly across the area. Taken together, these phenomena create physical gradients richly varied over time, and over short distances in a given time. In a single visit it is not unusual to find several distinct communities of microorganisms within a one-meter radius.

When we first examined the Weep in fall 2006, the bottom was deep orange. As the fall progressed, the orange area shrank to the Weep’s north end and the main stream took on a more yellow hue (left). The large orange-red pennate diatom shown at top left initially dominated the microbial community and continued to dominate in the retreating orange. The yellow hue resulted from the lovely diatom Cylindrotheca, shown on the bottom left, along with a larger filament of cyanobacteria. The dark tracks in the mud are left by feeding birds.

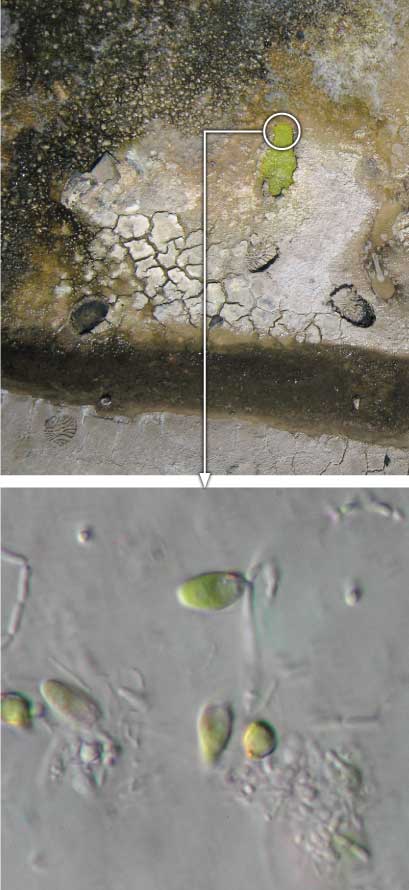

In winter 2007, the Weep took on a green color when the dominant microbial community consisted of cyanobacteria, both single-celled Chroococcus and a filamentous mat of Oscillatoria. The Chroococcus belongs to a group of cyanobacteria that includes Prochlorococcus, by biomass the world’s most plentiful organism. Every fifth breath you take contains oxygen produced by Prochlorococcus.

By May 2007, the salinity had risen dramatically and the ancient bacteria Halobacterium and the dinoflagellate Dunaliella dominated the Weep. These organisms are so salt-tolerant that they can be found swimming in pockets of water inside salt crystals.

.jpg)