Twice a month from October to March Audubon California volunteers spread out along the shores of Richardson Bay, pull out their spotting scopes, and count the birds they see bobbing about on the horizon.

This December they saw a familiar mix of species: cormorants, grebes, ruddy ducks, scaups, and buffleheads — striking black and white sea ducks whose iridescent green and purple heads shine on sunny winter days.

But there was a surprise. At more than 21,000 birds, the tally in Richardson Bay this December was higher than any year since the surveys began in fall 2006 — much higher. The previous high was 13,000 birds. “This year we destroyed that record,” says Kerry Wilcox, the sanctuary manager at Richardson Bay Audubon Center & Sanctuary. “It’s very encouraging.”

And if this year was all about volume, scaups certainly did not disappoint. The December survey tallied a combined 16,000 greater and lesser scaups, making them the most populous bird on the bay — easily confirmed by the presence of dense floating flocks that often contain thousands of individuals. While the overall Richardson Bay numbers have gone down since December, the last few weeks of counts have still produced a large volume of waterbirds, and overall sanctuary staff consider it a huge year.

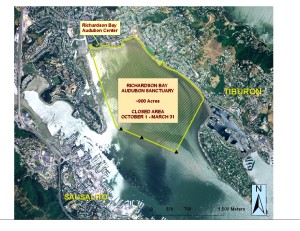

Tens of thousands of migratory ducks, cormorants, and shorebirds stop in Richardson Bay in the winter months. Some stay for a few days to rest before continuing south, while others stay the entire season. The rest of the year the bay is relatively quiet. “We do have some beautiful terns, but overall this isn’t a great place to bird in the summer,” says Jordan Wellwood, the sanctuary’s director. “The bulk of the birds floating on the bay are winter migrants.”

December through February typically sees the greatest spike in bird numbers, which correlates with the annual Richardson Bay spawning of Pacific herring. As the small fish come by the ton into the shallow waters of the sanctuary to spawn, their eggs sway on murky green eelgrass beds, blanket docks and pilings, wash ashore, and provide a veritable smorgasbord for the gulls and ducks that hungrily pluck them up.

But it wasn’t always such easy pickings. Herring populations have been declining since 2000 and have only recently bounced back from a record low of 4,800 tons in 2008 to almost 80,000 tons this year, which could explain the corresponding jump in bird numbers. Even porpoises and sea lions, visitors not normally found in Richardson Bay, have been spotted dining on the fish along with the usual assortment of pelicans, cormorants, and harbor seals.

But not everyone is showing up to the table. “One thing you don’t see is a lot of scoters out there,” Wilcox says.

With their bulbous red, yellow, and white bills, scoters are a colorful diving duck that have become something of a poster species for the health of the Bay, due to their declining population. “The general trend over the past four to five decades is downward and no one is exactly sure why,” Wilcox says.

And the birds don’t exactly make themselves easy to study. Scoters prefer to hang out in the deeper waters on the edges of the sanctuary or completely outside of it in the middle of San Francisco Bay, and aren’t easy to spot from shore. So once a year pilots with the US Fish & Wildlife Service take to the air and get a birds-eye count of the population. Although this year’s numbers haven’t been tallied yet, last year fell far short of the target.

Scoters breed farther north than most other ducks, building their nests on permafrost along the banks of shallow lakes. Scientists don’t yet know how this habitat is changing, but it is likely that the effects of climate change are more pronounced there. And with warmer winter temperatures, insect and other invertebrate prey may be emerging earlier in the season, before scoter ducklings hatch and have a chance to feed on them.

Scientists also worry that environmental contaminants such as mercury picked up in the Bay may be harming scoter breeding success. But scoter nests are spread out among vast expanses of boreal forest, and tracking them is no easy task. “There may be one or two hens on a little tiny lake,” says USGS biologist Susan de la Cruz, who studies the linkage between the winter and breeding habitats of Pacific coast scoters. And although some nests have been tracked, the eggs in them didn’t have particularly high levels of contaminants.

“There is no one smoking gun,” De la Cruz says. “It’s likely it’s several things, and people are desperately trying to figure it out.”

That’s one of the big remaining questions about this year: Scoters, like other birds, love herring roe. So in a good year for herring and a record year for birds, what’s going on with the scoters? Wellwood hopes to have an answer soon, when the results of the aerial survey conducted by the US Fish and Wildlife Survey come in.

But even if the scoter numbers improve along with other birds, Audubon California Seabird Conservation Manager Anna Weinstein says there’s no time to relax. Small fish like herring tend to fluctuate widely in their populations, and just because the numbers are up this year doesn’t mean they will stay that way.

Weinstein said the herring are doing well this year likely from a combination of good ocean conditions and more precautionary practices such as regulating dredging times and restricting boat activity during peak winter months in Richardson Bay, as well as fishery regulation that set strict quotas on herring catch to no more than 5 percent of the estimated biomass.

Fishermen once caught herring for their roe, widely considered a delicacy. But now that market is declining and fish are going into fish meal for pet food and other industrial products. So the fishery might benefit if the Bay Area’s famous food culture follows trends in sea lion consumption and starts to choose herring.

As more people begin ordering herring when they see it on menus, they will actually be increasing the value of the product. And that means fishermen can fish less for the same amount of money.

But Weinstein said she worries the long-term declining trend in herring numbers and increasing salinity in the bay due to the lack of rain this winter may harm herring eggs. She and her colleagues would like to see a fishery management plan developed that makes these healthy bay practices permanent, for the health of the herring fishery and all the animals, including humans, that depend on it.

“We want to protect what they need in good times and bad,” she says. “This area is only going to grow more dense. The time is now to identify and protect these areas from damage so herring always have these places to spawn.”