On January 22, 2011, at Bay Nature’s 10th anniversary gala, we presented our first “Local Hero” awards to three distinguished Bay Area citizens for outstanding lifetime achievement in the fields of environmental journalism (Harold Gilliam), environmental education (Dr. Doris Sloan), and conservation advocacy (Dr. Martin Griffin).

The following interview with Marty Griffin is the second in our series of in-depth conversations with our three awardees. The interview with Harold Gilliam appeared in the January-March 2011 issue; the interview with Doris Sloan will appear in the July-September 2011 issue.

It can be easy to take for granted the tremendous heritage of open space we have in the Bay Area. But for each precious parcel, someone had to envision the possibilities, strategize, organize, speak out, and fundraise to make it happen. Dr. Martin Griffin is someone who had both the vision and the tenacity necessary to create a legacy of protected land and wetlands in Marin and Sonoma counties.

As a young physician practicing in Marin County after World War II, Griffin came to see the destruction of the country’s shorelines and wetlands as a threat to the health of his patients and his community. In 1961, he engineered the purchase of the property along Bolinas Lagoon that would become Audubon Canyon Ranch’s key Bolinas Preserve, recently renamed the Martin Griffin Preserve, the first of many such significant victories. He was also a cofounder of the Environmental Forum of Marin and Friends of the Russian River. His book Saving the Marin-Sonoma Coast details the history of his numerous battles to protect our region’s coastal ranges, shorelines, and watersheds.

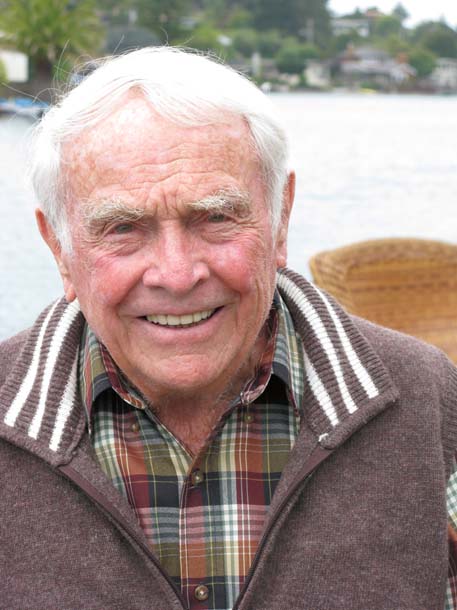

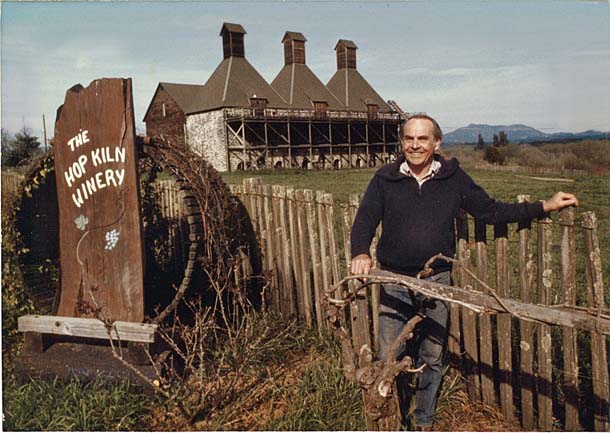

For many years, Dr. Griffin was also the owner of Hop Kiln Winery on the Russian River near Healdsburg. Now retired from both medical practice and winemaking, Dr. Griffin lives in Belvedere with his wife, Joyce, and still enjoys swimming and canoeing in Belvedere Lagoon.

DP: Where did you grow up?

MG: I was born in Ogden, Utah, in 1920. We moved to Los Angeles when I was four. There was a trolley car that went out to the beach and it was paradise. We moved to Portland and then to Oakland, where I was raised and went to the Oakland public schools. I love Oakland. Then I went to UC Berkeley and Stanford Medical School.

DP: How was nature a significant part of your growing up?

MG: My dad was a great fly fisherman, tied his own flies, and even made his own rods. When we were in Portland we would camp and explore wild rivers that were still undammed and teeming with fish. But my passion for nature really started at Boy Scout Camp Dimond, in Dimond Canyon in the Oakland hills. It was rich with birdlife, with giant redwoods and beautiful views of the Bay. Sausal Creek ran through the camp, with spawning salmon. Every youngster needs an outdoor experience like that to learn about nature. The nature program there was run by Brighton C. “Bugs” Cain, who created a museum we called the “Bug House.” He drove us in a big yellow bus to go camping in the wild places up and down the state.

DP: Wasn’t he was one of your mentors and heroes?

MG: I’d say Bugs Cain was one of the most influential people in my life. He inspired me to become an Eagle Scout and taught me how important it is to preserve habitat–open space, forests, the coast. He had many talents–he was a professional whistler and bird caller!

I remember he gave a talk to Rotary and had two rattlesnakes in a cage. He was demonstrating how to handle them but one of them bit him. He was very cool and calm about it. He said, “I need to get to a hospital and get an injection of antivenom. Would somebody please drive me?” He packed up his rattlesnakes and took them with him!

But World War II came and changed the focus of the Boy Scouts. They sold Camp Dimond and their High Sierra camp, Dimond O. That broke my heart. Everything I’ve done to save open space has been to make up for those lost camps.

DP: When did you first see Bolinas Lagoon?

MG: Oh that goes way back, to when I was 13 and went on a Boy Scout hike out there. We went by mass transit–took the train into Oakland and transferred to the ferry to San Francisco, then to the Sausalito ferry, and then to the electric train to Mill Valley. We got off in Mill Valley, hiked up what’s now the Dipsea Trail and down the Steep Ravine Trail, and camped in the dripping redwoods. In the morning we ran down the trail until it opened up on this incredible sight of Bolinas Lagoon and Stinson Beach backed by the majestic Bolinas Ridge.

Then later, during college, I majored in botany and zoology and took all kinds of biology courses. We went on a field trip to Bolinas Lagoon to see the heron and egret colonies there. They nested in the tops of redwoods and fed in the lagoon. I was really impressed. I resolved to come back someday and live there and I did. I bought a house right on the water in the ’60s with my then-wife, Mimi, the mother of our children. The lagoon and the canyons of Bolinas Ridge were our backyard.

DP: What led you to take on the battle to save Bolinas Lagoon?

MG: I saw that it was in danger of being ruined by a freeway. I was president of the Marin Audubon Society then, in 1960, and attended a hearing about a proposed coastal freeway in West Marin. I was horrified to see that the proposed route went from the Golden Gate Bridge, over the ridges of Mount Tam to Stinson Beach, then along Bolinas Lagoon, to the east shore of Tomales Bay, and up into Sonoma County. That’s exactly how the coast of Southern California had been destroyed. Nobody stopped that freeway!

But I had worked with Mrs. Caroline Livermore–who had started Marin Audubon–in the late 1950s to save Richardson Bay from a huge marina development. That gave me the knowledge of how to buy land to protect it from development, and so we thought we had a chance of preventing the freeway by buying land in the path of progress, so to speak. Our rallying cry was “Save Bolinas Lagoon!” I was able to secure an option in 1961 on what is now Audubon Canyon Ranch from William Tevis, who also owned thousands of acres on Point Reyes as well as this beautiful ranch that straddled the proposed freeway. I said I’d have to talk to Marin Audubon to see it they’d go along with the terms, and he said, “I’ll give you some of the land as a tax benefit for me if you can swing the deal.” I wrote him a check for $1,000 right on the spot because I had been taught by Mrs. Livermore to do that. She said, “FLASH THE CASH! SEAL THE DEAL!” You’ve got to get the cash out there or at least the option to buy it and worry about how to buy the rest of it later. I did that several times in the next 10 years, buying tideland lots that had been subdivided illegally by the state. (To this day in California, all tideland lots and rivers belong to the public under what is called the Doctrine of Public Trust.)

DP: What did Audubon think?

MG: National Audubon was appalled. They thought that Stan Picher–he was the treasurer of Marin Audubon–and I were developers and that we planned on subdividing the ranch. But I went back to Mrs. Livermore and she said, “You’re on the right track. If you can get this property in escrow, I’ll pledge $2,000 right now.” Marin Audubon was stunned that we had taken on such a big project but they said if Stan and I would be responsible for raising the money ($337,000), they’d back us up. So that’s how it happened. That was my first big experience in fundraising. We got all four Bay Area Audubon societies to join and create Audubon Canyon Ranch Inc., with 6,000 members. We paid off the ranch in five years. It was really the magic of the heron and egret colony that stopped the freeway and saved Bolinas Lagoon, Tomales Bay, and Point Reyes.

DP: Audubon Canyon Ranch just renamed the Bolinas Lagoon Preserve after you. How does that feel?

MG: Well, it’s humbling. I am really honored and thrilled. I am going to be on the map! A thousand acres of unspoiled paradise with four steep canyons–in memory of Camp Dimond and Dimond O. Precautions were taken so that none of ACR can ever be sold.

Shortly after starting ACR, we had a stroke of luck. I persuaded a patient of mine, Clarin “Zumie” Zumwalt, to retire from the U.S. Department of Forestry and become our head naturalist. For the next 35 years, Zumie taught lessons of nature to hundreds of docents, ranch guides, and maybe 20,000 school children and their teachers. My dream was to replicate Camp Dimond and Bugs Cain, and now we have five full-time naturalists in education, research, restoration, and preservation.

DP: Tell us how you got involved in the fight to save Tomales Bay.

MG: I was land acquisition chairman for ACR for 14 years, from the time we started in 1961. It was part of ACR’s strategy to stop the freeway and protect the portals to the Point Reyes National Seashore. There was tremendous pressure to develop Tomales Bay’s eastern shore because it overlooks this magnificent national seashore. It had developers thinking “Big money!”

Our strategy was to buy both tidelands and uplands to deny developers access to Tomales Bay and prevent them from building piers into the bay.

The battle for Tomales Bay really started in about 1967. The county came out with a master plan for the east shore of Tomales Bay. It stretched along almost six miles of the bay and had schools and cemeteries and the whole works for 150,000 people. It would have been the largest city on the North Coast, opening the coast to massive growth.

My first purchase on the bay was in 1970, the four-acre Shields Marsh parcel near Inverness that went out into the bay to Giacomini Marsh. When the state Wildlife and Conservation Board later that year purchased 500 acres of Giacomini, that end of the bay was secured.

The next parcel I bought was from Oscar Johansson, a rugged guy who had been oystering on Tomales Bay for about 40 years. I asked him, “Why do you want to sell?” and he said, “I want to get married!” He was 80 years old! Eventually ACR bought 44 acres of tidelands from him, including right in front of Cypress Grove, a 10-acre parcel on the eastern shore, one of the most magical spots you could ever imagine.

After we got those miles of tidelands, I had the courage to contact Cliff Conly, who owned Cypress Grove. I phoned him up when I got home from a late medical meeting; I didn’t realize how late it was. It was around midnight. I said, “Mr. Conly, this is Dr. Marty Griffin from the Audubon Canyon Ranch,” and there was deep silence. I could hear him breathing heavily. And I thought, “Oh my God, I’ve blown it.” Finally he said, “Okay, Dr. Griffin. I know who you are, and I like what you’re doing.” I told him we had just bought the tidelands in front of Cypress Grove and that we would like to make an offer for Cypress Grove.

He said, “I would never sell this place, but I’m standing here starkers in the middle of this ice-cold floor in the windiest, coldest part of California, and if you’ll let me get back to bed, I’ll give it to you.” And he did! It became our headquarters for saving Tomales Bay, just like Audubon Canyon Ranch had been critical for saving Bolinas Lagoon.

There was a big county supervisor election in 1968. Many conservationists threw themselves into that battle and won. That might have been the most important election in Marin history because in 1971 the new board killed the West Marin Master Plan and the new freeway plan. This was a land use revolution that saved Point Reyes National Seashore, which was completed in 1972. In 1973, the electorate of the Marin Municipal Water District voted nine-to-one against the aqueduct from the Russian River. That prevented a pipeline from bringing water to West Marin, keeping it rural.

As the huge development schemes for West Marin collapsed, Audubon Canyon Ranch expanded its holdings on Tomales Bay to 450 strategic acres. Our goal, along with State Parks, was to buy everything along the bay for nine miles, and that was done. We also purchased the delta of Walker Creek and the freshwater marsh of Papermill Creek. Also the winning of the Marks v. Whitney Public Trust lawsuit in 1971 helped protect the entire shoreline and tidelands of Tomales Bay.

DP: Tell me about Hop Kiln Winery.

MG: The owner was a feisty old guy who had a lot of real estate. I took a bottle of whiskey and knocked on his door. I got there after dark and I could see a fire going and a gun belt hanging from the fireplace and a shotgun in the corner, and I thought, this is a tough old guy. His name was Billy Walters, and he and I really hit it off.

The 300 acres I was interested in covered both sides of the Russian River, downstream from Healdsburg, with a creek running through it and a beautiful old hop barn. I knew I shouldn’t get it but I couldn’t resist . . . I got an option on it.

DP: Did you know that he had leased the floodplain to a gravel mining firm?

MG: I didn’t find that out until later when I had seen all the papers. There was a legal document that said he had leased 50 acres on both sides of the Russian River to this mining firm for 25 years to skim gravel off the gravel bar. But they went down 60 feet! I have pictures of it. It would just make you sick.

DP: When you went back and saw this dredging that was supposed to be skimming, you must have been shocked.

MG: I was. When I bought the place, word got around that this kooky environmental doctor who had ruined development in Marin County had bought the ranch, so the mining company went in there immediately and started dredging. They also went in with their chain saws and cut down all these magnificent trees, including two with osprey nests. There were egrets and all kinds of wildlife. I was devastated. I became the chairman of a statewide group to try to control gravel mining. Our lawsuits resulted in a mining plan and a watershed management plan for every California river.

DP: How did you juggle your life as a conservationist with your career as a doctor and your role as a family man?

MG: Well, I wasn’t entirely successful, if the truth be known. I think I worried my wife about spending too much money and time on environmental matters. But we lived a great life here in Marin County with our family of four daughters and a good medical practice. But I guess I did pay a price for years of stress. I had surgery on my coronary arteries six years ago. They grafted veins from my legs on four of my arteries. Two of those are for the pit gravel mining fights, one was domestic–but we won’t go there–and one was my mother. She had a knack for pushing me!

When I was 14 or 15, I was working on a knot-tying merit badge for the Boy Scouts. One of my neighbors was Jimmy Wilson and my mother said his knot board was much better than mine, so I better get busy. She found an old San Francisco seaman, a square-rigger sailor who knew all kinds of knots. So I went over there once a week to learn. The knot board with 200 knots now adorns a wall in my garage. My mother kept egging me on saying Jimmy’s knots were better.

DP: I bet she was responsible for your determination through so many battles.

MG: Oh yeah, she made me strong . . . it was worth an artery!

DP: What do you see as some of the greatest challenges in the Bay Area now?

MG: I think the biggest environmental challenge is still San Francisco Bay and its watershed, including the Delta and the rivers that flow into it. There’s a lot of work to be done there for equitable water supply and restoring the ecology of the Bay and Delta.

Population growth in the Bay Area and California is a huge issue. The growth is around 400,000 to 600,000 new people every year. The state can’t sustain that level of growth with water, food, schools, transportation, and social services.

This is one of the unique areas in the world with its Mediterranean climate and its abundance of rare plants and animals, the redwoods and the magnificent coastlines and San Francisco Bay. It’s really incredible that so much open space has been permanently protected. But when I say permanent you really have to be careful because that open space can be usurped.

It’s going to take a major effort, something like the Marshall Plan, to save California. It’s not just about saving land. It’s about education, sustainability, jobs, and getting youth involved in protecting the state’s resources. There’s still so much to save here. And with global warming coming on, it’s a real challenge.

There should be a minimal state standard for everyone that they have to know certain things about ecology and the earth. You get a driver’s license and maybe you should get an earth knowledge license to learn the basic facts about air and water and soil.

Being a physician has helped me understand my relationship to the earth, and I think everyone needs to understand that they are part of the earth, and they’d better take care of it.

.jpg)

.jpg)