Jim Walsh had his eyes to the sky during the 2010 Great Backyard Bird Count at King Ranch in southern Solano County when a cloud of western meadowlarks flushed from the grass and circled above his head. Their bright yellow breasts flashed while he estimated a count. When he entered the number into his computer at the end of the day, the automated program spat back, “Are you sure?” Walsh’s estimate of at least 3,000 birds was off the charts.

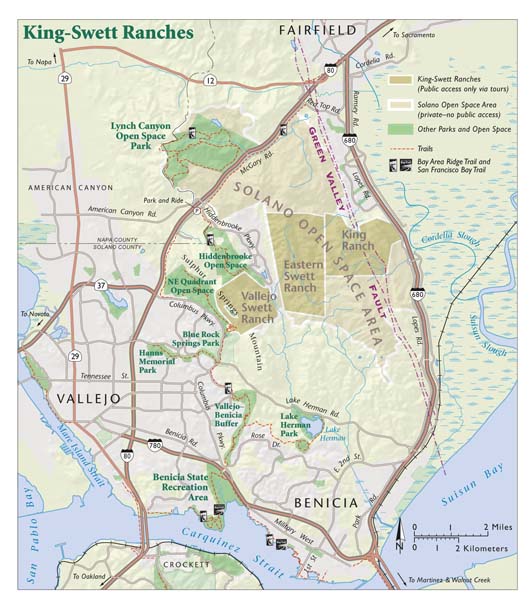

King Ranch is part of a protected expanse of hills and valleys nestled between the cities of Vallejo, Benicia, and Fairfield. You get a sense of the 3,956-acre King-Swett Ranches as you drive eastbound on Interstate 80. After leaving the developed flatlands of Vallejo and passing the turnoff for Highway 37, you press the accelerator to climb into a range of mostly undeveloped hills while admiring the volcanic outcrop to your right. This taste of the rural inner coast range lasts for several miles before you drop into Fairfield and the flat span of the Central Valley.

The spread of cities, and the inevitability of cities blending into one another, prompted officials from Vallejo, Benicia, Fairfield, and Solano County to collaborate in the early 1990s on a plan to protect a 10,000-acre open space buffer between the county’s three largest cities. They made it part of their mission to protect natural resources, preserve agriculture, and provide public recreation for this swath of land they dubbed the Solano Open Space Area. They reached 50 percent of their acquisition goal when the Solano Land Trust purchased the King-Swett Ranches in 2005. (The land trust’s 1,039-acre Lynch Canyon west of i-80, purchased in 1996, also falls within the Solano Open Space Area.)

Even though the land is protected and the Solano Land Trust has a public access plan ready to go, the gates remain locked most of the time. “We have been successful in finding capital funds for acquisition,” says Bob Berman, a longtime open space advocate and a Solano Land Trust board member. “The dire need now is to find a permanent source of funding for operation and maintenance.” Solano County is alone in the Bay Area in its lack of some sort of countywide open space or park district with dedicated funds.

For now, you can explore the King-Swett Ranches on monthly docent-led tours, best described as explorations rather than clearly defined hikes. While there are some ranch roads and trails on parts of the 4,000 acres, there are just as many routes that follow cattle trails or have no trails at all. (It’s fun, but wear your hiking boots with ankle support.) Jim Walsh has been leading these hikes for eight years. Upon meeting his group on the first Saturday of each month, he gives an overview of the three separate ranches here–King (1,617 acres), Eastern Swett (1,433 acres), and Vallejo Swett (906 acres). Then he describes any exciting things he’s seen lately and lets the hikers choose what to explore.

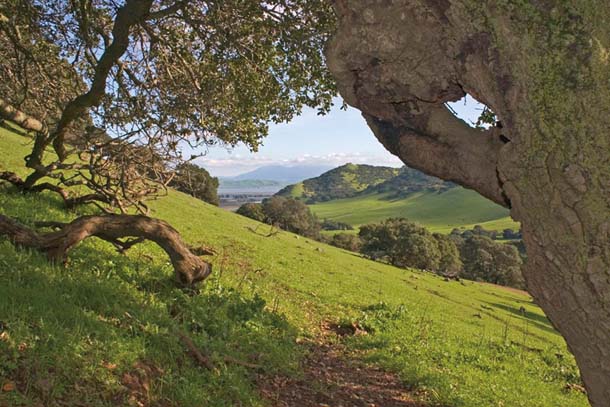

On a recent fall hike at Vallejo Swett, we set off on a trail choked with yellow star thistle; popped down to a gully to see what kind of fish were in the pool (we couldn’t tell); followed the gully until it turned into a mature creek lined with coast live oak, arroyo willow, and black walnut; climbed a steep hill without trails to the upper reservoir; crossed the open grassland bowl of the ranch to explore the serpentine outcrop on the northwest corner; and returned on a paved road cracked open by weeds and weather. We chalked up a nice array of bird sightings: flocks of crows carrying unshelled walnuts; Lincoln’s, Savannah, and grasshopper sparrows; Say’s and black phoebes; red-shouldered and red-tailed hawks; northern harrier; osprey; a snowy egret; and hundreds of meadowlarks. We also looked for Swainson’s hawks, overwintering burrowing owls, and eagles, all birds that have been seen here. One day at King Ranch, as Walsh was telling hikers that they were likely to see a golden eagle, a bald eagle flew overhead.

Hawks and eagles are the Blue Angels here, but meadowlarks are the ambassadors, their yellow chests decorated with a black “ribbon,” their outer white tail feathers flipping like tuxedo tails. In the dozen or more times that I’ve visited, I’ve never failed to hear their song. If there is a soundtrack to the King-Swett Ranches, its dominant note is that of the meadowlark, synonymous with grasslands.

Today, nonnative grassland is the primary habitat at King-Swett Ranch, but that may not have always been the case. In a 2007 botanical survey for the Solano Land Trust, botanist Samantha Hillaire observed that the property to the south of King Ranch includes oak woodlands with a mixture of coast live oak, blue oak, California buckeye, valley oak, elderberry, and California bay laurel. Extensive sheep and cattle grazing in the 1800s and early 1900s likely altered the habitat here.

Ted Swiecki at Phytosphere Research points to clues on the land to show that the lack of tree cover is likely due to human activity and not the natural state of affairs. First, if the soil had always eroded at the same rate it does without the protection of trees today, the parent rock would be exposed everywhere instead of just in patches. Second, oaks don’t grow from seed in isolation, and the current distribution of oaks on the property is consistent with deforestation rather than natural dispersal. And third, patches of oak woodland understory, such as poison oak, appear randomly on the properties, unshaded by oaks.

A few tenacious trees still stand. A stunted, old blue oak, now protected by a cage, sits atop a windy hill at King Ranch, and a cluster of valley oak clings to a steep slope at Eastern Swett. The riparian corridors host more variety: bay laurel, coast live oak, black walnut, arroyo willow, and buckeyes.

Buckeye flowers provide nectar for butterflies including the callippe silver-spot, a federally endangered insect whose presence has been confirmed on all three ranches. The larval plant food for this butterfly is Johnny-jump-up, a native Viola, but the adults feast on nectar from mints, thistles, and buckeyes. According to entomologist Richard Arnold, who conducted a survey for the Solano Land Trust in 2007, Johnny-jump-up grows on about 400 acres here.

Several special plant communities occur on the properties. A 2006 botanical survey shows 62 acres of serpentine grassland, which supports a bouquet of native bunchgrasses and wildflowers. A spring walk to the serpentine outcrop at the western edge of Vallejo Swett reveals blue dicks, silver puffs, California poppies, tidytips, Tiburon buckwheat, yarrow, bush monkeyflower, and California bee plant.

Sue Wickham, Solano Land Trust’s project manager, never visits the properties without a canvas bag to fill with acorns or seeds from narrow-leaved milkweed and other native plants. One warm fall day, Wickham and I set out to pick acorns at King Ranch. Along the way, she showed me evidence of the Green Valley fault, including a wide break between houses in Cordelia to the north, where mandatory setbacks reflect the trace line of the fault that runs through the development. Looking south, she showed me the differences in terrain. On the east side of the fault, large rocks were strewn across the brown grasses, and volcanic outcrops poked out of steep-sided hills. On the west side, no boulders were visible on the surface of the hills. If you were to dig through the soil, she said, you’d find sedimentary sandstone, not volcanic rock.

We continued south on a trail that hugs a steep slope above what she calls Fault Line Creek and stopped to pick acorns from a coast live oak. The low-hanging branches made the acorns easy to reach, and our timing meant that the ripe nuts pulled easily from their crowns. Wickham will store the acorns in a refrigerator, the modern way, and use them to plant more trees as part of the several research and stewardship projects that she supervises. At King Ranch, where a spring-fed pond provides a home for federally endangered red-legged frogs, the land trust (with mitigation funds from Pacific Gas & Electric) fenced the pond and 16 surrounding acres, removed artichoke thistle by hand, and planted 100 native trees. Cattle grazing is strategically used at the start and end of the rainy season to keep nonnative grasses down. “We’re seeing a marvelous regime of wetland and riparian grasses, including creeping wild rye,” Wickham says.

At Eastern Swett, the valley oak trees and their seedlings are monitored by Solano Community College professor John Nogue and his biology class. Another frog pond at King Ranch is the domain of two volunteers, Maggie Ingalls and Linda Sonner, who have successfully removed cocklebur and artichoke thistle around the pond and its three-acre uplands.

“The greatest threat to the property is weeds,” says Wickham, who this year found two species of noxious weeds new to the property. Until recently, artichoke thistle covered these lands. Several years ago, the land trust joined a regional effort to eradicate the plant. It’s now mostly gone from King Ranch and Vallejo Swett, but the thistle has a 10-year seed bank, so the weed monitors must continue to be vigilant. That may not be enough. “There is no money for weeding right now,” says Wickham, “but we can’t expect volunteers to do it all.” Having a park district could help by providing specialized staff and steady, sustainable funds, she says.

Of course, this whole region was once open space, part of a vast 84,000-acre cattle ranch owned by General Mariano Vallejo. The property was subsequently broken up into smaller ranches, which remained in private hands for decades until pg&e bought the land in 1980 for a potential residential development or wind turbine site. (An outhouse held down with steel cables testifies to the wind’s power at King Ranch.) Neither option proved feasible, so the utility sold the property to the land trust.

The land trust then conducted a survey of the land’s natural resources and hired landscape planner Randy Anderson to prepare a public access plan. “I have worked on a lot of different open space projects, and none had as many important resources as this property does,” Anderson said in 2007. He reiterated the importance of having staff rangers to manage people and protect resources and suggested the property be declared a nature preserve.

The board has approved an access plan with 30 miles of trails for hiking, biking, equestrian use, and pack-in camping. But it will need money and a partnership to proceed. “Land trusts aren’t set up to be park districts,” says Marilyn Farley, who led the trust when King-Swett was purchased.

The idea of a countywide park system is gaining support at the grassroots level, says Duane Kromm, a former county supervisor. To illustrate, he points to the recent acquisition of Rockville Trails, the 1,500-acre open space purchased by the Solano Land Trust. “The community came together and pulled off this huge multimillion-dollar fundraising effort,” says Kromm. For Rockville Trails, the land trust factored maintenance and management into its fundraising goals.

“Of all the properties that could be potentially folded into a magnificent park district, such as Lynch Canyon, Lake Herman, Rockville Park, Rock-ville Trails, and others, the King-Swett Ranches are unique,” says Berman. “The thing that’s so great about them is their close proximity to three cities, Vallejo, Benicia, and Fairfield.”

Now that’s something to sing about.

Getting there

The Solano Land Trust offers guided hikes on the first Saturday of each month. Head east on I-80; exit at American Canyon/Hiddenbrooke Parkway. Meet at the park-and-ride. Details at solanolantrust.org.

Solano County resident Aleta George, a frequent Bay Nature contributor, writes about nature and culture. Her work has also been published in Smithsonian and High Country News.